Cicadas are emerging by the thousands in the Northeast, and “a lot of people use them as a great learning tool for their kids,” says research scientist Dr. De Anna Beasley. “They don’t bite, they don’t sting; it’s a great natural science experience.”

She hopes everyone will relax about the noisy insects. People ask about pesticides, she said, but cicadas are not harmful or toxic. “They are only around four to six weeks,” she says. “ There’s no need.”

“It’s a really cool natural phenomenon,” she added. “It’s kind of amazing. I tell people to just enjoy it.”

The large, red-eyed insects are not skittish. A person can easily approach one and pick it up. They are edible, and people in some cultures consider them a treat and fry them with spices. Beasley has not included that experience in her research, but “I imagine the larvae taste like shrimp, and the adults would be very crunchy.” She knows of people in America who have put them into ice cream, she said with a laugh. Cicadas are non-fat and high in protein.

The males are mostly hollow, so they would not provide much meat. Their hollow abdomens are musical instruments—the source of their loud mating songs. Each type of cicada has its own song, and females only select singers from their own tribe. Brood 19, which emerged in South Carolina in 2011, had three distinct mating songs, and the females could pick out the right songs despite the cacophony, according to Beasley. This 2013 northeastern Brood II is similar, she said.

When the cicadas mature, they come to the surface with two things on their minds--making music and making whoopee.

They don’t even feed much while they are above ground, according to Beasley. The females make a slit on the underside of a tree branch and lay hundreds of eggs in the slit. The larvae fall to the ground, burrow into the tree roots, and feed and grow for their allotted time.

Mysteriously, the creatures always have a prime-number based life cycle. No one knows why, according to Beasley. This year’s brood emerges every 17 years. Another brood comes out every 13 years, and there are other types that mate and lay eggs annually, every five years, or every seven years. It’s never an even number.

Cicadas rely on trees to live, so they are vulnerable to habitat loss. Researchers know that some broods have gone extinct because of urbanization. At the same time, “there could be hundreds of thousands in an area. It can be pretty staggering, the numbers that emerge,” said Beasley.

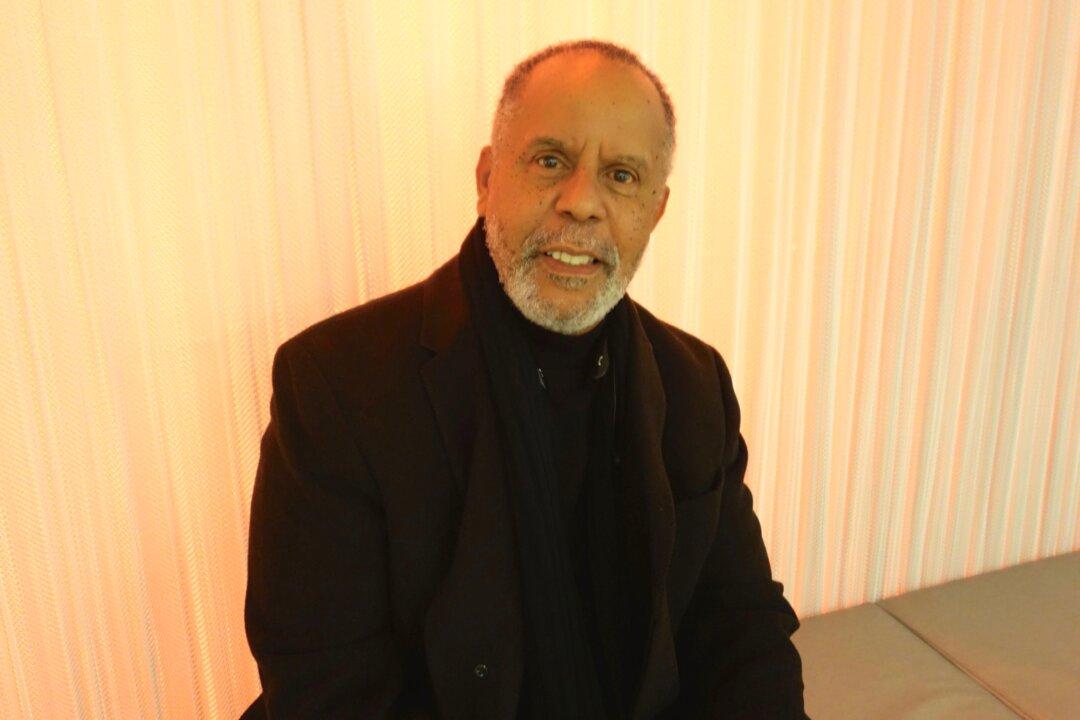

Beasley had planned to be a medical doctor, but late in her pre-med studies realized that a medical career was not what she wanted. She read various research papers until the idea of studying insects for what they reveal about environmental conditions intrigued her. That is how she became a cicada expert. She finished her doctoral work at the University of South Carolina at Columbia.

For math and science majors, there are so many things to do beyond being a doctor or a vet, according to Beasley. “See what catches your eyes and sparks your interest,” she said.