Chinese human rights lawyer Liu Xiaoyuan recently posted a picture of himself on Twitter selling pesticides on the street in Beijing. He also announced that he started a new business after his law firm’s license was suspended. His post may have embarrassed the Chinese authorities, as they notified him on the following day that his license to practice law was suspended.

In the picture, Liu sits on the curb, next to a small vending cart, holding a board that reads: “Fly glue trap, Cockroach killer, Rat glue trap.”

Liu wrote in his Twitter post: “I, Liu Xiaoyuan, a Beijing lawyer who has become unemployed through no fault of my own, will not rely on government social assistance programs or financial help from the Lawyer’s Association. Although I am over 50, I have decided to start my own business. I will make a living by selling poisons and devices that can eliminate the ‘four harms.’” “Four harms” is a Chinese term referring to four major types of insect pests.

A report from Radio Free Asia revealed that the Judicial Bureau of Chaoyang District in Beijing informed Liu on June 19, the day after he posted his street vendor picture on Twitter, that his law license had been suspended.

The person notifying him also told Liu that he was the only lawyer in Beijing whose license had been suspended this year, while there were quite a few suspensions last year.

Liu, a former partner at the now-abolished Fengrui Law Firm, provided legal services and counseling to political dissidents and victims of social injustice for over ten years, such as victims of the tainted milk scandal. He was repeatedly detained by Chinese authorities on different charges, including “crime of starting quarrels and provoking troubles,” a typical accusation used by Chinese authorities to punish rights activists.

Liu told Radio Free Asia that he considered suing the authorities, but a similar case by rights lawyer Cheng Hai wasn’t successful.

“Cheng Hai appealed when his license to practice law was revoked, but the court refused to accept the case,” Liu said. “[The authorities] can’t tolerate the existence of rights attorneys like us ... I can’t even protect my own rights, let alone defend other people’s rights. How can I be a lawyer in today’s climate? I am disappointed with this society and the judicial system. It might be more accurate to say I am in despair.”

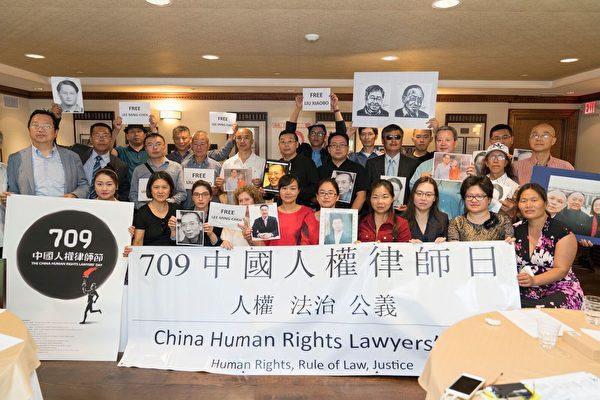

Liu and dozens of his colleagues at the Fengrui Law Firm were arrested by Chinese authorities on July 9, 2015 during a nationwide crackdown on rights activists and lawyers known as the “709 Incident.” Hundreds of lawyers, legal assistants, and human rights activists were raided and taken into custody.

Many of these lawyers had their licenses suspended or revoked. License suspension means the lawyer cannot practice law for four years, while license revocation permanently terminates one’s career as a lawyer.