“Cang Jie invented the characters, thereby millet grains fell down from heaven and the evil spirits cried in the night.”

This is how Chinese have passed down the legendary tale of the invention of the Chinese characters by the ancient bureaucrat, Cang Jie, 4000 years ago.

Author and painter Zhang Yanyuan explained during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) the reasoning to above story as follows: “The heavens can no longer keep their secrets from human beings. Humans would, when learning the characters, recognize the secrets of the heavens. That is the same happy act of providence as millet grains falling down from the heavens.”

The evil spirits can now no longer hide, because human beings can now recognize, through the characters, the fundamentals and principles of the world. Therefore, it is no longer possible for these spirits to cheat and lie to people. The only consolation the spirits now have is to secretly cry during the night.

The Chinese characters are the treasure of treasures of the Chinese culture. The Chinese speak of “unity of heaven and humans,” which is also reflected in the Chinese characters. The Chinese characters contain the teachings of I-Jing, the five elements, and the Taoist Yin-Yang; they carry extensive information about heaven, earth, humans, events and objects, and these connections are all illustrated through the combination of the characters. That is also how in ancient China fortunetelling on the basis of characters came into being.

Xu Shen, a researcher in the Dong Han Dynasty (25-220), analyzed the structure of the Chinese characters on the basis of the teachings of the I-Jing and the five elements, and documented his studies in the most important book on Chinese in history, called “Explaining Simple and Analyzing Compound Characters” (說文解字 shuōwén jiězì).

In his book Xu Shen divided the Chinese characters into six categories:

象形 Xiàngxíng, pictographs “depicting directly”: These display the meaning through directly depicting the appearance (for example: 山 for mountain, 人 for man, etc.);

指事 Zhǐshì, ideograms “pointing out the facts”: These are like conceptual pictographs, in that they represent an abstract idea through a picture. (for example: 一, 二, and 三 for “one”, “two”, and “three”; and 上 for “up”, 下 for “down”.)

會意 Huìyì, ideogrammic compounds “combination of meanings”: characters that consist of two or more characters with different meanings and whose contents are combined to create new characters (for example: 安 “peace” is a combination of “roof” 宀 and “woman” 女, meaning “all is peaceful with the woman at home”)

形聲 Xíngshēng, phono-semantic compounds “form and sound”: characters which consist of one sound component and one meaning component. (for example 媽 mā means “mother”, the right component 馬 is pronounced mǎ and means “horse”—it indicates the phonetic element—while the left component is 女 (nǚ, meaning “woman”), and this gives the meaning. The meaning component is often a “radical” (one of about 200 ‘building blocks’ of characters which make up the Chinese written language). About 90 percent of all Chinese characters fall in the Xíngshēng group.

假借 Jiǎjiè, phonetic-loans “under false name”: the reasoning behind these characters is slightly more complex, and relates to the historical development of written Chinese. In ancient China, one character would often be used for more than one meaning. But as the character was passed around, the more common character would end up “borrowing” the earlier one. For example, 來 was the pictogram for “wheat”, but it was also used for the verb “to come”. Eventually the more common “to come” became the default meaning of the character 來, and a new character for “wheat”, 麥, was established.

轉注 Zhuǎnzhù, reciprocal meaning “turn and pour”: this is a purely historic categorization, and refers to characters that have the same etymological root but which have diverged in pronunciation and meaning. 老lǎo “old” and 考kǎo “test” is a common example.

Man and Woman

男 stands for man. This character again consists of two more characters. The character in the upper part, 田, means field, the lower part, 力, means strength. Men are supposed to be strong, and work in the field. This is how the classic “Explaining Simple and Analyzing Compound Characters” describes it. In ancient China it was said: “Men rule the affairs on the outside”, therefore farming, war, fighting, being an official, and conducting business were all affairs of the men. A man is first the son of his parents; then when he gets married, the husband of his wife, and when they have children, the father of his children.

女 stands for woman. All characters with 女 have something to do with a woman, such as 妻 (wife), 妇 (housewife) and 媽 (mother). The upper part of 妻 (wife) is a broom, and the lower 女 , for “female” or “woman”. Women in China took care of the affairs in the household, such as cooking, cleaning, and sewing.

義 (Yi)—Justice, Honesty, Loyalty

The symbol 義 has broad inner content, and includes values such as justice, honesty, loyalty and reliability. It is composed of羊 (sheep) on top and 我 (I, myself) on the bottom. The sheep is obedient and kind, and mutton tastes good and is nutritious.

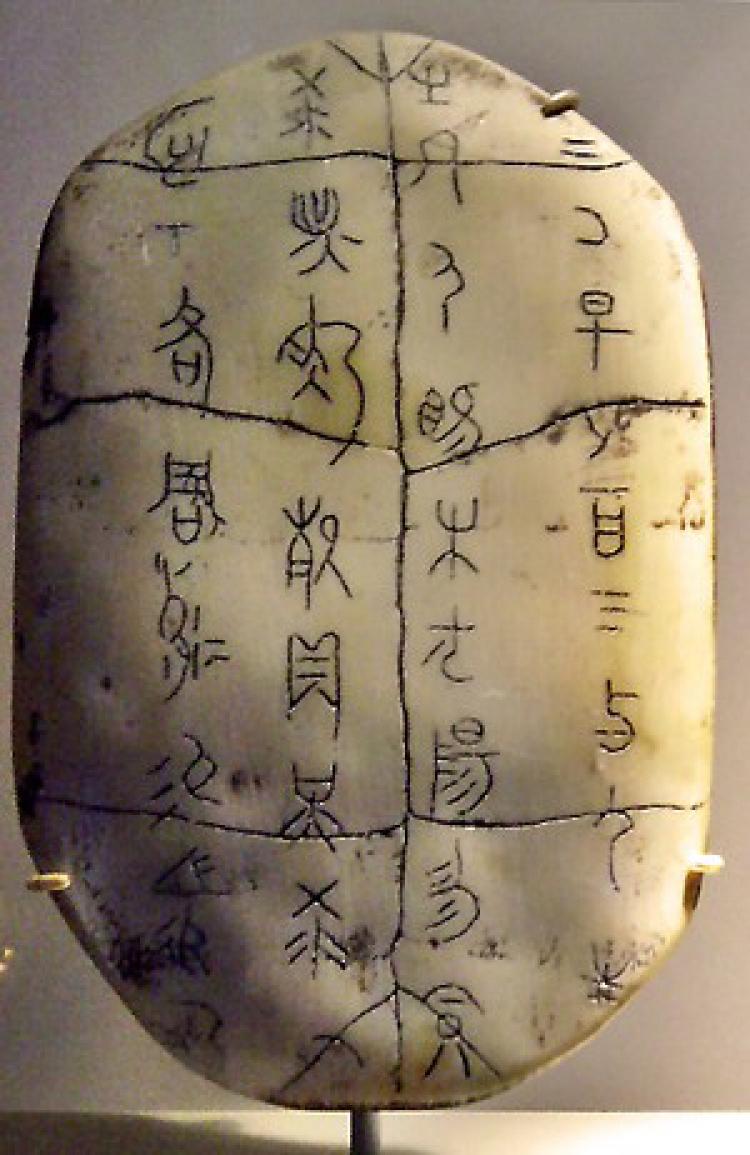

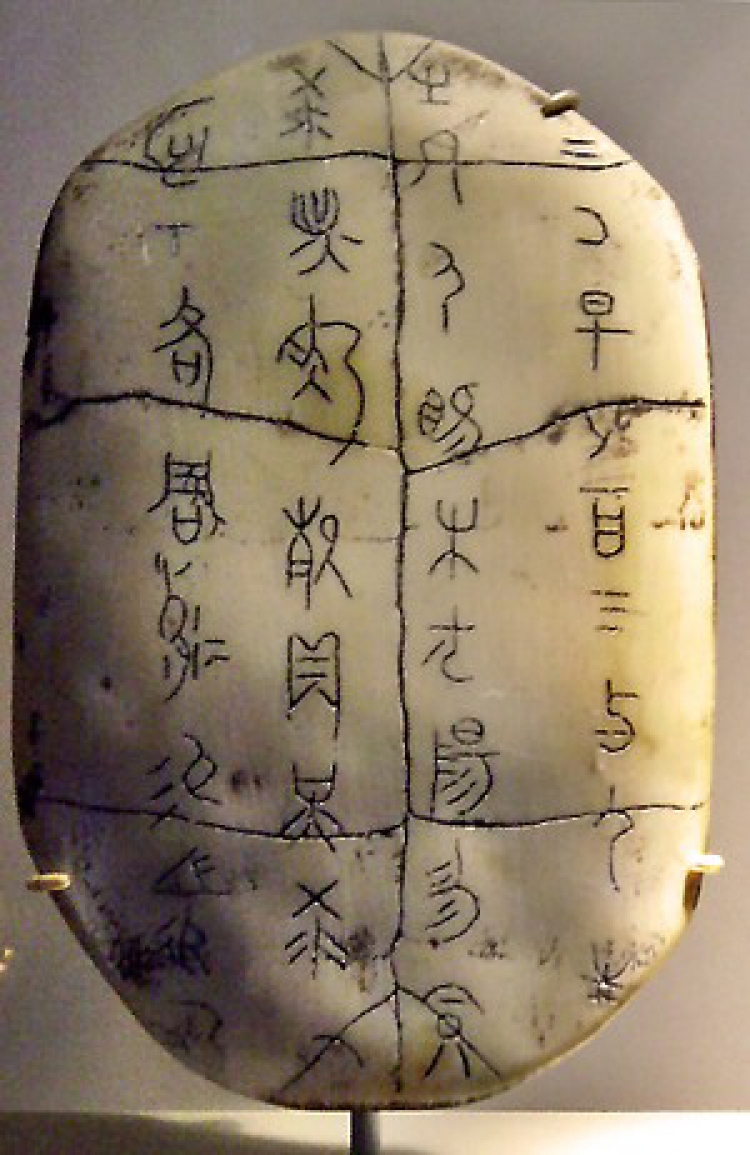

Given those characteristics, the sheep was considered to be a symbol for good luck and prosperity. “我” was originally developed from the oracle bone script where it denoted a fighting implement with a sharp tooth. 我 and 羊 going to together to make 義 can be interpreted literally to signify “I am a sheep.”

It means that it is possible to make sacrifices in the name of justice, similar to sacrificing a sheep to honor the gods. The Chinese character 義 reminds people how they should be conduct their lives, that is, selflessly. 義 belongs to a special category of ideograms, called huiyi characters (multiple meanings brought together); they are composed of ideograms with different meanings and their inner contents are a fusion of the several meanings.