Beijing is quietly overhauling how Chinese firms handle data, and these changes are likely to have global implications.

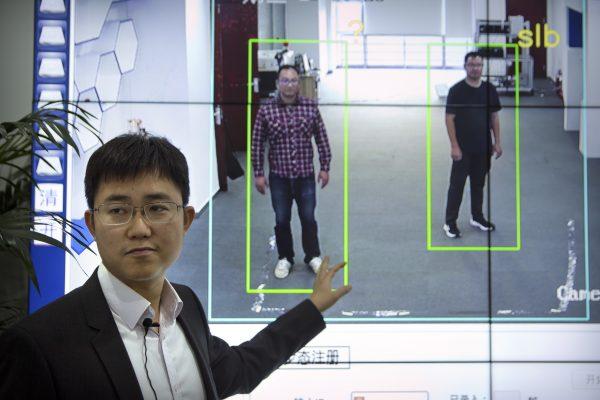

The management of how firms handle data has historically drawn little interest. But with the advent of internet-connected devices that can track or measure virtually every movement, governments have taken an increasing interest in who’s managing what and where data is stored.

In the last few weeks, the importance that the regime in Beijing places on controlling Chinese data has been made clear. Recently, a new law in China went into effect with the stated intent of safeguarding Chinese data. This has had an immediate effect on not just firms in China, but firms from around the world for seemingly basic data.

Driving this change is Beijing’s view of what constitutes a national security risk. Historically, countries have thought of weapons, military strength, or top-secret research as national security data. However, that view is changing and China is ahead of most other countries in considering what constitutes a national security risk in the age of Facebook and Twitter.

China uses a vast array of domestic firms to collect data on foreign individuals and institutions around the world, relying on the openness of liberal democracies and the internet to gather information. It uses this data to classify and better target individuals it wants to approach or technology it wants to acquire. This open-source data is processed, analyzed, and provided to the state.

However, China goes even farther than open-source intelligence gathering. A vast array of devices manufactured or coded in China collect usage data on hoovering up information on products and consumers. Recently, a Chinese point of sale firm in the United States was raided when it was discovered that its terminals were sending data back to China.

Understanding the value of that data for national security purposes, given its collection on foreign individuals and institutions, Beijing is well aware of the potential for Chinese data to be used against China. Chinese fishing vessels have cooperated regularly with the People’s Liberation Army Navy, being referred to as the “maritime militia.” With Didi, China has been very protective of its digital maps for many years, purposefully shifting coordinates so that maps don’t translate digitally between countries and electronic operating systems.

However, even as authorities seek to bring all Chinese data under state control and protection, they’re seeking to remake data availability to the state within its borders. Beijing is pushing a data trading plan, encouraging Chinese firms to trade data and even creating centralized repositories. For firms outside of China, this idea would be an anathema.

Tech firms treat user-generated data as proprietary, giving them an advantage in generating better ads or sales possibilities for users. Not only would tech firms such as Google or Facebook likely open themselves up to legal liability by trading user data, but they would also lower their competitive edge.

However, in China, trading data creates greater pools for the government to access. Notably, it reduces the competitive edge of tech firms such as Alibaba that are seeking to sell more products to their customers if more firms have access to the same data. Willfully or by accident, in seeking to remake the data landscape for improved government control of key data, Beijing is killing the competitive advantage of tech firms. Thus far, there’s little evidence that this practice will spread beyond China, but only time will tell.

A primary goal of Beijing is to block access to Chinese data by global firms, but retain access to foreign data by Chinese firms in their civil-military fusion state. That should say everything about how Beijing values and wants to use data.