As China pursues its ambition to lead the world in artificial intelligence (AI), it also broadcasts its financial commitments to funding large projects that support AI development.

Western analysts attempting to gauge and compare China’s AI spending versus spending in the United States, however, run up against barriers to the analysis, an Institute of Defense Analyses (IDA) report concludes.

We are “unaware of any persuasive discussion about whether such comparisons are credible, in light of uncertainties about the Chinese estimates,” the report states.

Building on a September 2019 IDA report, the current report looks into Chinese data gathered from official Chinese state sources. Focusing on four Chinese funding mechanisms known to support AI development, researchers came to an unexpected conclusion.

Of billions of dollars of publicly announced spending on Chinese AI, only $138 million is found to be “potentially comparable to U.S. expenditures on non-defense AI R&D,” the report concludes.

That doesn’t mean that China isn’t spending what it says it’s spending on AI, the report says; it also doesn’t mean China isn’t spending even more than it has announced. It indicates that the systems by which the United States and China disclose their relative data are so fundamentally different that no comparisons are possible.

The Science & Technology Policy Institute (STPI), which produced the IDA report, benchmarked its own estimates with those made by other organizations.

“Our expenditure estimates are lower than others from the literature, when viewed as a percentage of total expenditures examined within each funding mechanism,” they found.

The mechanisms to which IDA refers are Chinese programs that are the result of a 2014 reform that consolidated a mixed and underperforming pool of science, technology, and innovation programs into five groups.

All five of these programs are publicly competed in China, according to STPI researchers, which means that open-source data “should exist.”

Four criteria were used to compare U.S. federal spending in AI research and development (R&D) to potential Chinese counterpart spending.

Any Chinese expenditure had to be, first, made by the Chinese central government. Second, and logically, it had to be focused on AI. Third, it had to be focused on R&D. Fourth and finally, it had to be viable.

The criteria of viability was then determined by deciding whether an expenditure was actual, estimated, budgeted, or aspirational.

The research results were nearly unanimous in their analysis of the four national-level Chinese groups that IDA/STPI studied, which include the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), National Key R&D Programs (NKP), Megaprojects, and Government Guiding Funds (GGF)

Because these funding mechanisms were specifically and deliberately chosen for their public competitiveness, the researchers argue that “they are among the most transparent of Chinese funding mechanisms.” Yet, only two of the four, NSFC and the NKPs, “make sufficient data publicly available to analyze their entire R&D portfolio,” IDA suggests.

Megaprojects and GGFs, on the other hand, may not even have useful data in the public realm, making them impossible to compare with U.S. AI funding programs.

But the NSFC and the NKPs whose data are public and comprehensive enough to be able to compare to U.S. programs are themselves only “responsible for about 10 percent of the $60 billion that the Chinese central and local government expended on non-defense R&D in 2018.”

IDA/ STPI’s final conclusion is stark.

“Given the opacity of the publicly competed funding mechanisms, we find it unlikely that the remaining 90 percent of China’s non-defense R&D portfolio can be analyzed at a similar fidelity as the 10 percent that we ... have investigated.”

The impact of what is certainly deliberate obfuscation of hard numbers that the Chinese government is devoting to AI research can cause “alarm among U.S. policymakers,” the researchers state.

Allen referenced a program in Shanghai that purports to be spending “$15 billion over 10 years” just on its own municipal AI programs, while the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency is spending “$2 billion over five years.”

“So, literally, we have the U.S. federal government at present at risk of being outspent by a provincial government of China,” Allen says. “They are really spending jaw-dropping sums on this area.”

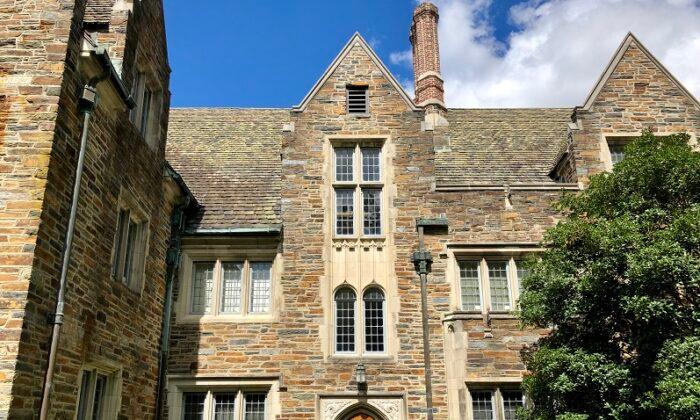

The Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET) at Georgetown University, however, comes to a completely different conclusion.

Ultimately, it concludes that “China’s government probably spent a few billion dollars—and at most, closer to $10 billion—on AI-related R&D in 2018, with basic research comprising a small fraction of the total.”

It seems that comment applies to other statistics released—or perhaps more importantly, not released—by Chinese officials. The U.S. assessment of AI spending in China may indeed be a victim of China’s success in artificially and purposely clouding the issue entirely.