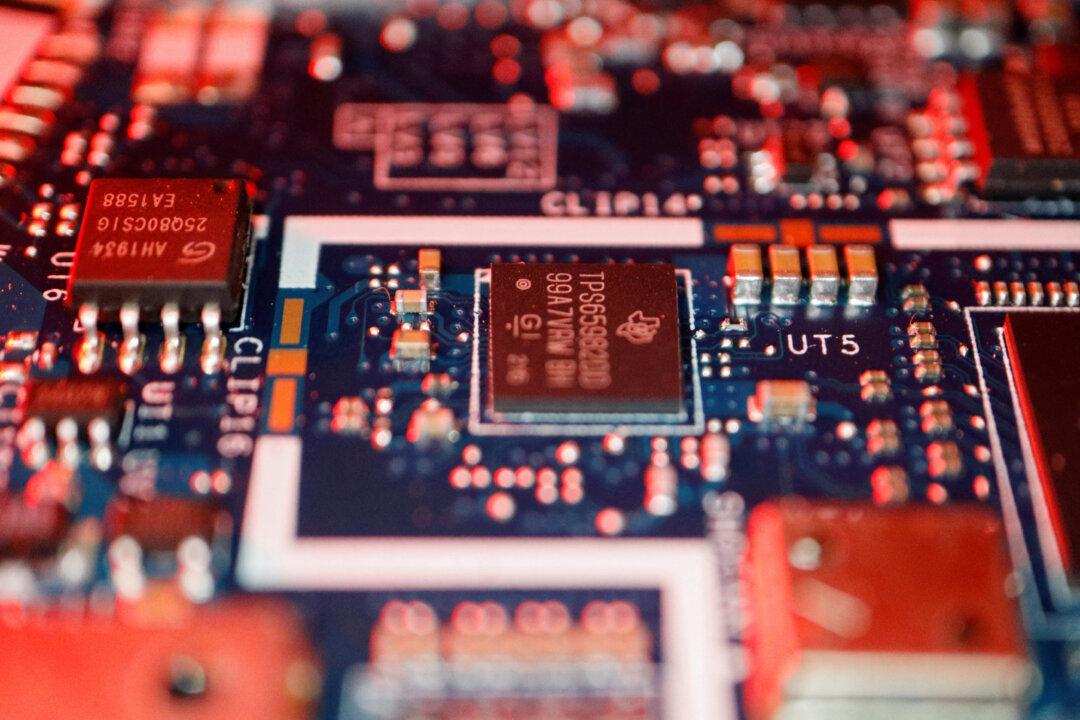

Bipartisan House lawmakers on May 15 introduced a bill aimed at preventing the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from accessing advanced U.S. semiconductor chips.

The United States has put export controls on advanced chips since 2022, intending to cut off the CCP’s access to cutting-edge technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI) technology, that would advance its military. But they have not had the intended effect because of smuggling, loopholes, and technological developments, according to the eight lawmakers introducing the Chip Security Act.