The strategy is part of an “obsession” with comprehensive national power on the part of China. The Party hopes to quietly and secretly build this power while weakening the existing regional strategic order in Asia.

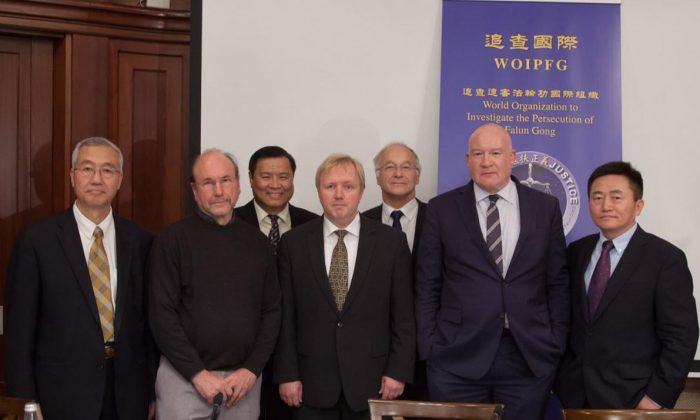

John Lee, a research fellow at the Center for Independent Studies in Australia and visiting fellow at the Hudson Institute in Washington, gave his analysis as part of a panel discussion on Oct. 27, held at Hudson.

Based on an extensive review of official, strategic, and Party documents, he suggested China’s grand strategy in Asia had four planks:

- Avoiding military confrontation with a much more formidable military power, (i.e., the United States), while building the most formidable comprehensive power of any Asian country.

- Gradually weakening the appetite for an American presence in Asia, and diluting the viability of alliances. This is to be done without provoking overt tension with the United States.

- Building regional acceptance of Chinese strategic, economic, and cultural leadership.

- Increasing the incentives for America to cede leadership of Asia to China without military conflict.

As an example, the Party’s military buildup has been largely about making the cost of American military intervention in Asia prohibitive. “Ideally the Chinese plan is to win a war without fighting,” Lee says.

Alongside these goals, China is also actively aiming to “dilute, circumvent, supersede, or transcend,” and sometimes dismantle, American strategic alliances in the region. This includes finding windows of opportunity to target rifts in bilateral ties between Asian states and Washington, and attempting to limit U.S. freedom of action in the region. This is all without provoking a response from Washington. “A pretty clever strategy,” Lee observed.

Part of this weakening of strategic alliances takes a “bottom up” approach, whereby the Party suborns the economic and social elites of Asian nations so they will put pressure on their governments not to take the U.S.’s side against China in any potential conflict.

Since the imperatives of the governments in many such countries lie not necessarily in long-term strategic interests, but regime longevity, these plans are generally coasting along, Lee indicated.

China is strengthening the incentives and willingness for states to bandwagon behind China in the future, restricting the options of, or isolating those countries that don’t fall into line, creating significant disincentives for the United States to use force to reverse this gradual change, and attempting to decisively rid the South China Sea of the United States navy, Lee said.

“It’s about free riding under the current set up, relentlessly building comprehensive national power at the expense of America, subtly weakening the post World War II security architecture in the region, and easing America out of Asia in the longer term.”

Though there are a number of constraints to these plans, both internal and external.

Domestically, there is instability and disorder; one-fifth of the country is governed passably, but 80 percent of the country isn’t due to weak institutions and myriad other problems; demographic crises loom; mass unrest continues around the country; and the economic model, based on enormously wasteful investment projects led by state-owned banks, is unsustainable. “It’s a very rich, strong state, but a very poor, weak, country,” Lee said.

Further, Chinese strategists work in a setting in which Beijing is “mistrusted by every major power in Asia, including Russia,” Lee pointed out. China shares borders with over a dozen countries, none of whom are genuine allies, making it the “loneliest rising power in world history,” Lee says.

After two other speakers—Dan Blumenthal of the American Enterprise Institute, who spoke about how Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan are responding to China’s rise, and Andrew Shearer of the Lowy Institute in Sydney, Australia, who spoke about Australia’s response to China— Hudson senior fellow Seth Cropsey responded to Lee’s thesis by arguing pointedly that the United States needs to restore the ideas that were at the core of its foreign policy at the beginning of 20th century.

“We need to change our ideas about China,” Cropsey said. “They are at odds with how China sees us.”

He compared the current China-U.S. dynamic with the unbalanced mutual conceptions between the Venetians and Ottomans in the 15th and 16th centuries. Even after the Ottomans took Constantinople, the Venetians assumed commerce was the mainstay of the relationship, not strategic competition.

The Ottomans, on the other hand, were playing for keeps. The two powers ended up in a war that the Venetians only barely won. “Venice was spent, finished, in serious decline from which it would never recover,” Cropsey said.

While he did not predict a similar fate for the United States, his message was that when American leaders engage with a rising China, led by the Communist Party, they should do so with eyes wide open.