A new Senate bill that would allow Canadian border agents to examine contents stored on travellers’ personal digital devices if an officer has “reasonable general concern” sets a low standard that fails to protect individual privacy, a civil rights group says.

Bill S-7, the Liberal government’s proposed legislation that seeks to amend the

Customs Act and the

Preclearance Act, doesn’t provide a clear definition as to what constitutes a “reasonable general concern.”

The Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA), in a May 16

news release, described the threshold as “very low (and legally novel)” and said it “does not adequately protect travellers’ privacy.” It’s “a sniff test, not a standard,” and it’s not used anywhere in the Customs Act and Preclearance Act or in any other legislation the CCLA has identified so far, the civil rights group added.

According to the bill, if the threshold of “reasonable general concern” is met, it would allow a Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) officer to “examine documents, including emails, text messages, receipts, photographs or videos, that are stored on a personal digital device that has been imported or is about to be exported.”

The CCLA said that “introducing such a low standard not only fails to protect individual privacy, but also fails to offer protections against racial and religious profiling that may stem from the excessive discretion such a minimalist standard will provide, and may even exacerbate such profiling.”

To protect travellers, a minimum threshold of “reasonable grounds to suspect” should be established, the CCLA said. It noted that this is consistent with a

2017 recommendation from the House of Commons standing committee on access to information, which said this threshold should be required for searching electronic devices in order to protect Canadians’ privacy at the U.S. border. Another acceptable option would be to set up a standard of “reasonable grounds to believe,” which appears in the Customs Act and Preclearance Act.

“These standards are individualized, not general, and therefore would provide more robust privacy protections against unreasonable searches of personal electronic devices at the border. Either would also provide greater protections against racial and religious profiling,” the CCLA said.

The bill came after the Alberta Court of Appeal ruled in

the 2020 R. v. Canfield case that it is unconstitutional for border service officials to examine the contents of a personal electronic device, such as a cellphone or laptop, under the Customs Act, because the relevant section of the legislation didn’t impose limits on when and how a device search can be conducted.

The court also noted that the ability to examine an individual’s “biographical core of personal information” in an “unlimited and suspicion-less” fashion goes against

Section 8 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedom, which states that “everyone has the right to be secure against unreasonable search or seizure.”

Bill S-7

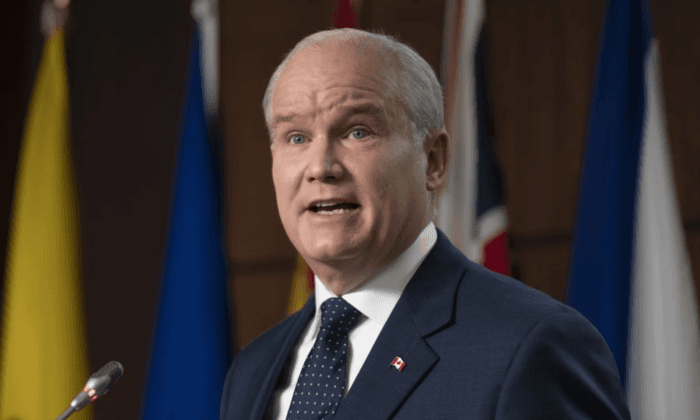

was introduced by Senator Marc Gold on March 31, 2022, on behalf of Public Safety Minister Marco Mendicino.

In

a statement released that day, Mendicino said the proposed updates to the legislation “will institute clear and stringent standards that must be met before a traveller’s device can be searched, while ensuring that the CBSA can continue to fight serious crimes like child pornography and keep our borders secure.”

The bill was not introduced to the House of Commons before it appeared in the Senate, where it passed second reading on May 11.

Under

Canada’s current law, CBSA agents are allowed to examine all goods travellers have with them when they cross the border if the officers have concerns that border laws have been broken. Travellers’ digital devices may be examined when there are concerns regarding their admissibility, the admissibility of their goods, their identity, or their failure to comply with Canadian laws or regulations.

From November 2017 to December 2021, 33,373 people—or 0.013 percent of the over 253 million travellers coming to Canada—had a digital device examined, according to the CBSA.