Commentary

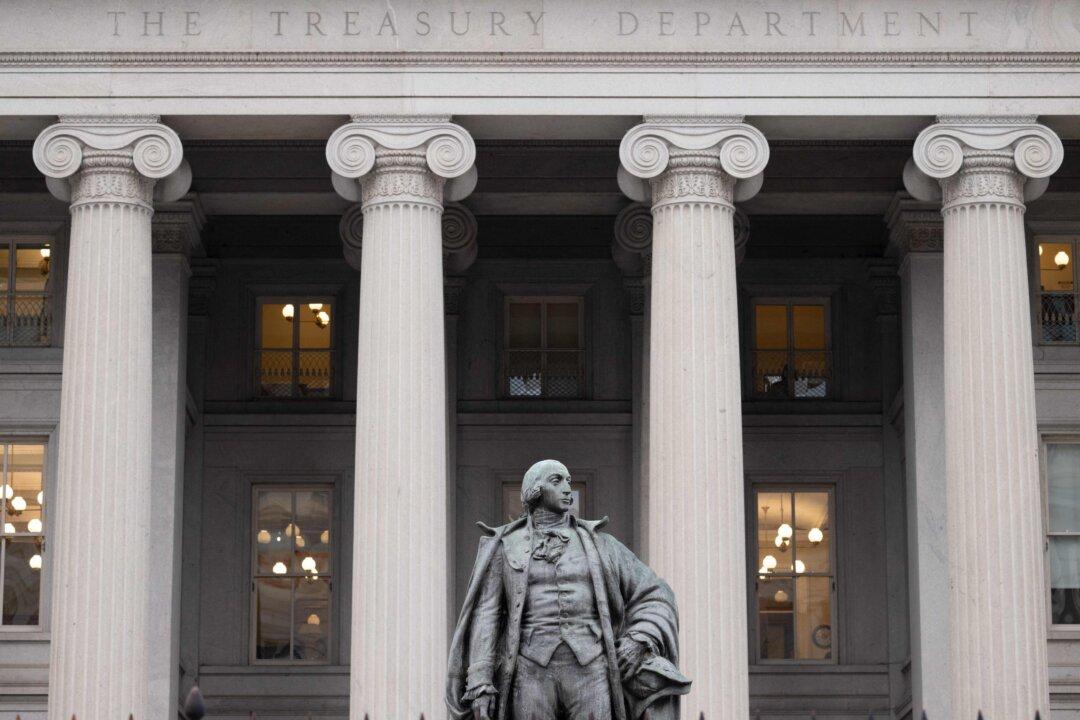

In the early summer of 2003, then-Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan shook his head, looking at a steady fall in the yields of Treasury notes. The U.S. economy was expanding, as numbers showed, almost two years after a recession in 2001 that followed a late-20th century boom. The war in Iraq a few months earlier had been wrapped up quickly, as far as removal of dictator Saddam Hussein was concerned. Above all, the stock market was rising briskly after the benchmark S&P 500 Index’s painful 50 percent correction in 2000–02. Mr. Greenspan had feared that the U.S. economy was slipping into mild deflation for unforeseen reasons, similar to which Japan had been mired since the mid-1990s.