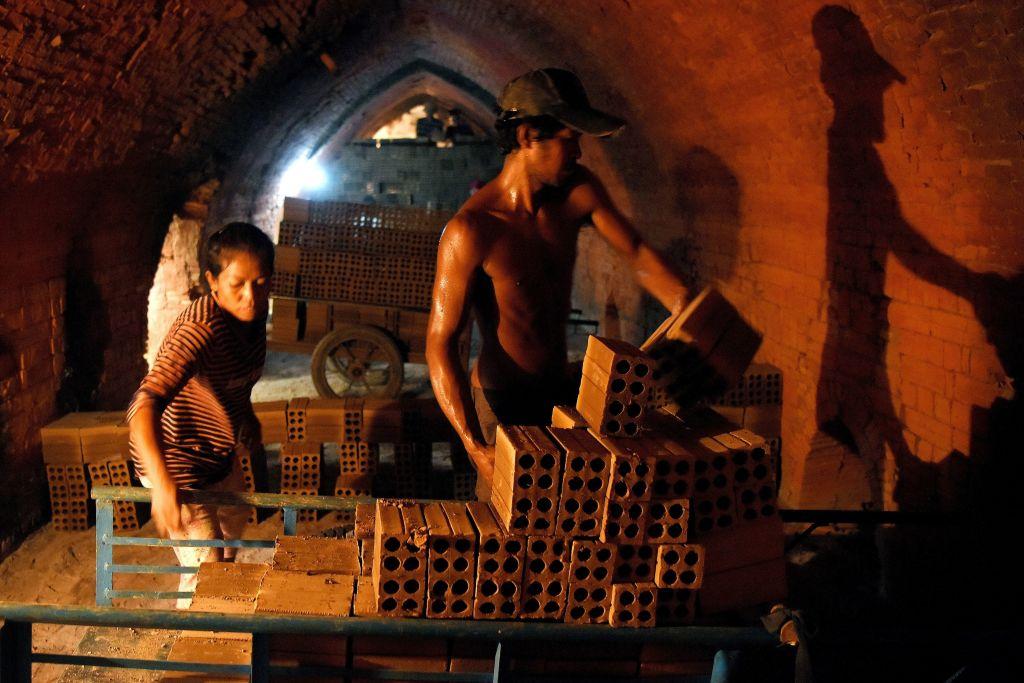

Garment waste from major global brands are being used to fuel Cambodian brick factories, leading to dangerous health hazards for workers, according to a recent report.

The Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights (LICADHO) visited 21 brick factories in the country between April and September this year. Seven of these factories used garment waste from 19 international brands, including Reebok, Under Armour, Lululemon, GAP, Old Navy, Primark, and Walmart to fuel their brick kilns, stated a Nov. 20 report from the organization. Brick kilns are furnaces in which bricks are baked or burned.