News Analysis

BIRMINGHAM, England—At first glance, it looks like British politics has lurched hard to the left.

Described as a “hard left” socialist by some members of his own Party, Jeremy Corbyn garnered 40 percent of votes in the recent U.K. election, with a self-declared Marxist, John McDonnell, as his would-be treasury secretary.

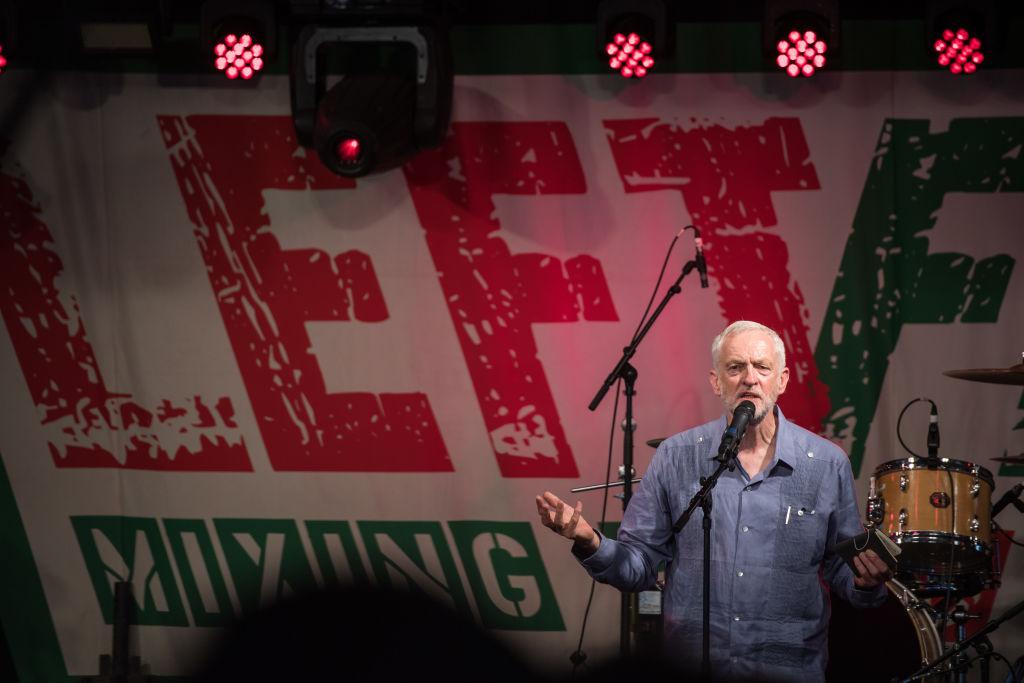

A few weeks later, when the Labour Party leader appeared on stage at Glastonbury Festival, a crowd of tens of thousands chanted his name.

But the surge in Corbyn’s popularity doesn’t actually reflect a growing public appetite for hardline socialist ideals, say political experts and Party moderates.

Corbyn’s ideological stance is hard to pin down, and is interpreted differently by different supporters.

Corbyn’s policies and rhetoric were seen as an unpopular leftist throwback to the 1970s by many senior figures even from within his own Party, which had long since been pulled toward the center ground by former Prime Minister Tony Blair. When Conservative Party leader Theresa May called an election in March, her Party had more than double Labour’s points in the polls.

The Labour Party braced for a drubbing. Then the unthinkable happened: Corbyn surged in popularity, and the Party gained 30 seats, stripping the Conservative Party of their majority status and forcing May to team up with a minor Party to form a government.

The election result doesn’t mean public opinion chimes with Corbyn’s socialism, says Steven Fielding, a professor of political history and director of the Centre for British Politics at the University of Nottingham.