‘BioBank’ a Backward Step for Conservation

“BioBank”, the New South Wales Government’s new environmental management scheme, devalues rather than values open natural areas, say environmentalists.

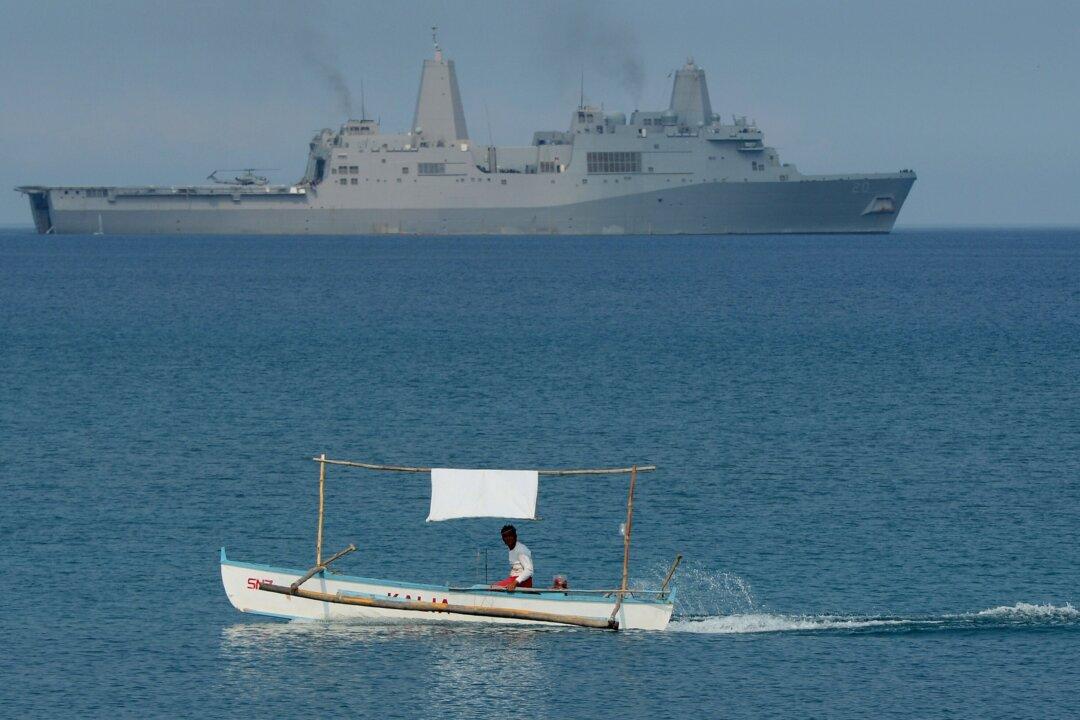

BioBank will sacrifice one nature reserve to save another, say environmentalists. Lucas Dawson/Getty Images

|Updated: