ATLANTA—One thing I like to think about is how the earth can regenerate. Consider the multiple mass extinctions our planet has seen. In the Permian-Triassic extinction event about 250 million years ago more than 90 percent of species perished. Yet look at the richness of life today.

Rachel Carson’s 1962 book “Silent Spring” predicted a world without birds due to indiscriminate pesticide overuse and water pollution. However, just this weekend I saw a great blue heron, mallards, bluebirds, robins, brown thrashers, mockingbirds, hawks, cardinals, goldfinches, and many other birds in my city. America made a huge effort to clean up its air and water, and it is working.

25 Neighborhoods

We’ve made some environmental improvements, but more work still needs to be done. In Atlanta where Proctor Creek has been piped, channeled, and polluted, a water nymph is languishing. The city grew over its ecosystem. An industrial sector used and abused it.

According to a statement from the EPA, “The Proctor Creek watershed, part of the larger Chattahoochee River watershed, is 16 square miles with a population of 127,418 people living in over 25 different neighborhoods. Decades of neglect have resulted in numerous environmental challenges—from tire dumping and brownfields to impaired water quality and pervasive flooding.”

A Shining Dragon

In Hayao Miyazaki’s 2001 film “Spirited Away,” the heroine, Chichiro, works in a spa. A hideous, mute blob arrives for a bath, but no one wants to get near it. They say it’s a stink spirit. Chichiro bathes it anyway. She finds what she thinks is a thorn in the blob, pulls it out—and it’s a bicycle, the first thing in an avalanche of polluting junk. When she finishes cleaning her client, it transforms into a shining dragon and flies away. It was really a river spirit.

I thought of that shining dragon when I visited Proctor Creek. A lot of Chichiros are working to free it. One of them is the federal government. Proctor Creek is 1 of 11 communities in the Urban Waters Federal Partnership.

The partnership includes multiple federal agencies, cities, neighborhood civic groups, nonprofits, and private businesses.

Government can do great things. But it can also—no disrespect—lumber too. It can bog down. And (no disrespect) it can (ahem) be corrupt. So I was encouraged to talk to some nongovernmental Chichiros working to heal Proctor Creek.

Open Doors

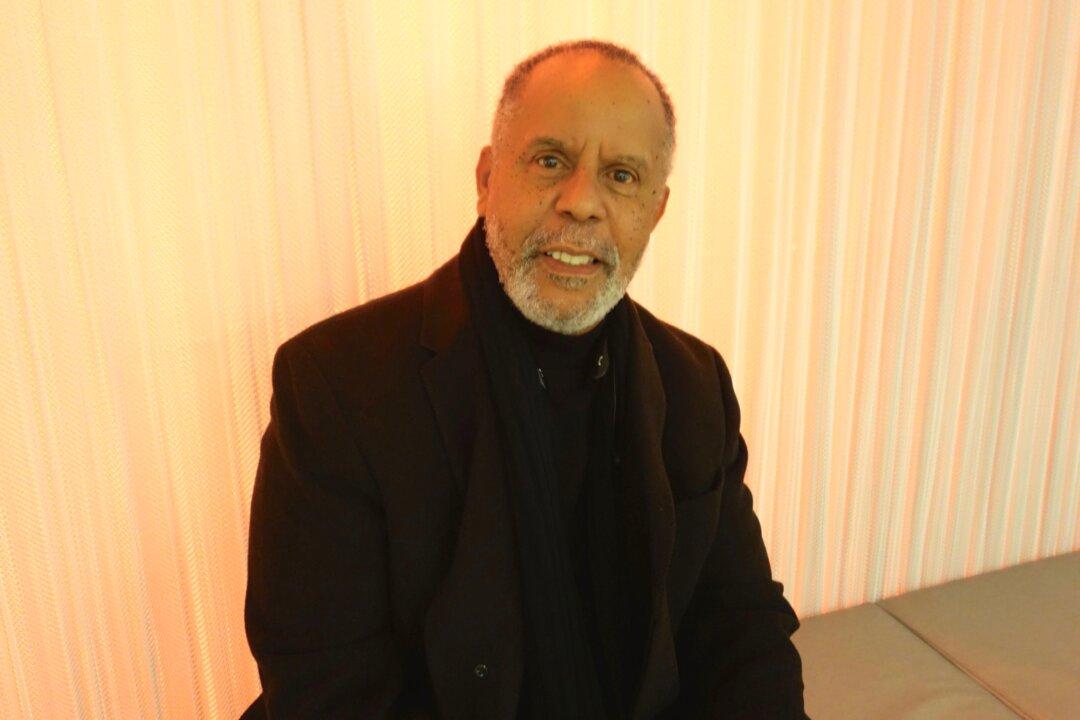

Emerald Corridor is a venture capital firm that opened an office nearly on the banks of the creek. Manager Joel Bowman said it was “key to put down roots in the neighborhood.”

The office is in a former gas station. Bowman said when they started to renovate it, it was like opening a tomb—tools were lying on tables as if the workers had walked away after a sudden disaster. Now it’s full of natural light from the original windows, with tables made of reclaimed wood.

“We have open doors,” he said. “Neighborhood groups meet here once a month.” It was important to Bowman not to be another LLC (limited liability corporation) based in Buckhead, Atlanta’s wealthy business and residential center.

A tall chain link fence surrounds the Emerald Corridor parking lot. A high bank behind the lot looks over a verdant field, with wildflowers and willows, where Proctor Creek explodes from its underground channels.

Right now the field is not a good place to stroll—you don’t want e. coli on your shoes. Water rushes downstream, eroding, flooding, and carrying pollutants from the city.

Once the area is restored, however, 500 million gallons of water can be filtered and restored to the aquifer, according to EPA estimates.

Emerald Corridor wants to remove asphalt and concrete in order to make the land around the creek permeable. First it must map the topography and plan how to mitigate the floodplain in detail. The feds must agree that its restoration idea will be effective. But the beauty of a government-business partnership is that the feds have already done much of the survey work, and Emerald Corridor can use it.

A High Line Veteran

My sister happens to work for one of the nonprofit partners helping Proctor Creek. Conservation group The Trust for Public Land (TPL) is built on a delightful libertarian model. It buys land to preserve it for people.

TPL Program Manager Debra Edelson helped develop New York’s High Line. She said that the industrial nature of the area, ironically, benefits the process of cleaning it up. “The history of industrial uses is what allows TPL to put together land.” It can’t displace people from their homes, but it can buy an abandoned factory.

The coalition’s goal is to create a green park corridor that extends to the Chattahoochee River, attracts good economic development to the neighborhood, and free that imprisoned river spirit. I'll follow this over time.