CANBERRA—The world may be focused on the “war on terror”, but the arms build up in North-East Asia poses a far greater threat to global stability, says Professor Desmond Ball, a senior defence and security expert at the Australian National University (ANU).

A former head of ANU’s Strategic & Defence Studies Centre, Professor Ball is no lightweight when it comes to security concerns. It is Professor Ball’s expertise in command and control systems, particularly in relation to nuclear war, that underlies his concerns about North-East Asia.

“North-East Asia has now become the most disturbing part of the globe,” Prof Ball told Epoch Times in an exclusive interview.

China, Japan and South Korea – countries that are “economic engines of the global economy” - are embroiled in an arms race of unprecedented proportions, punctuated by “very dangerous military activities”, he says.

Unlike the arms race seen during the Cold War, however, there are no mechanisms in place to constrain the military escalation in Asia.

“Indeed, the escalation dynamic could move very rapidly and strongly to large scale conflict, including nuclear conflict,” said Prof Ball. “It is happening as we watch.”

Arms Race

Military spending in Asia has grown steadily over the last decade. According to a 2013 Stockholm International Peace Research Institute report, China is now the world’s second largest military spender behind the United States, spending an estimated $188 billion in 2013.

Japan and South Korea are also among the world’s top 10 military spenders. When North Korea and Taiwan are included, North-East Asian countries constitute around 85 per cent of military spending in Asia.

But what is more disturbing, Prof Ball says, is the motivation for the acquisitions.

“The primary reason now for the acquisitions, whether they are air warfare destroyers, missiles or defense submarines, is simply to match what the other [countries] are getting,” he said.

While he believes it is likely that Japan would have embarked on military modernisation, he says it is China’s military provocation of countries across Asia that is fuelling the build-up.

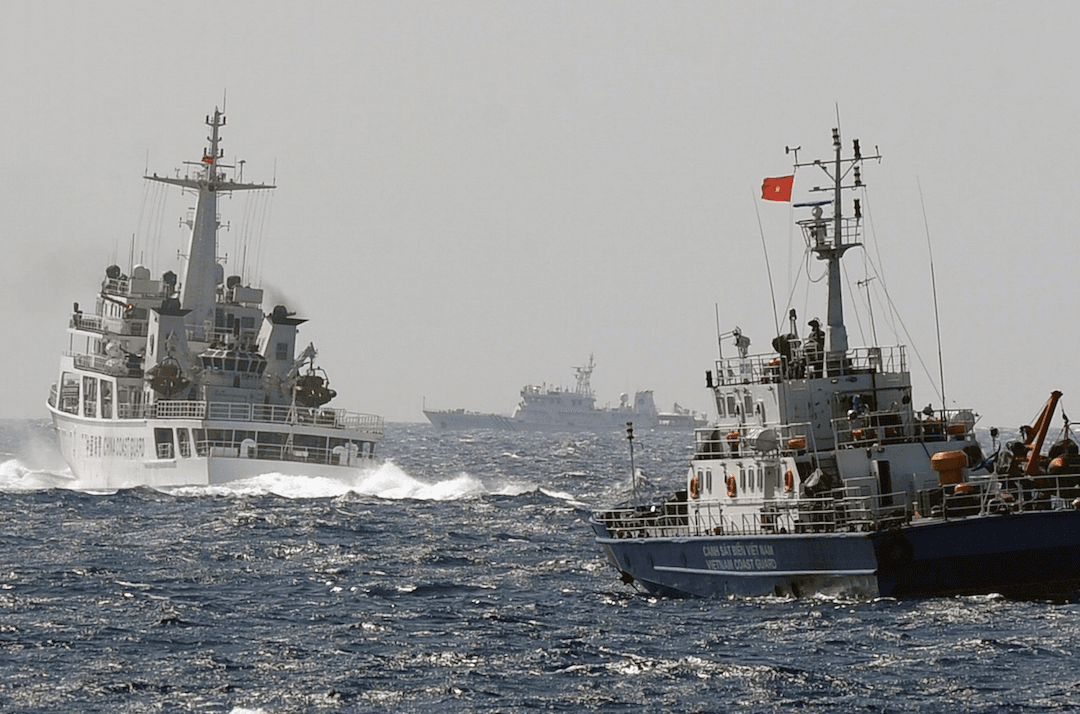

Since China lay claim to all of the South China Sea, it has escalated territorial disputes with Vietnam, the Philippines and Malaysia.

What started with skirmishes between locals and Chinese fishing boats or navy vessels has now become territorial grabs – island building on contested rocky outcrops.

In a sign of things to come, the South China Morning Post reported in June: “China is looking to expand its biggest installation in the Spratly Islands into a fully formed artificial island, complete with airstrip and sea port, to better project its military strength in the South China Sea.”

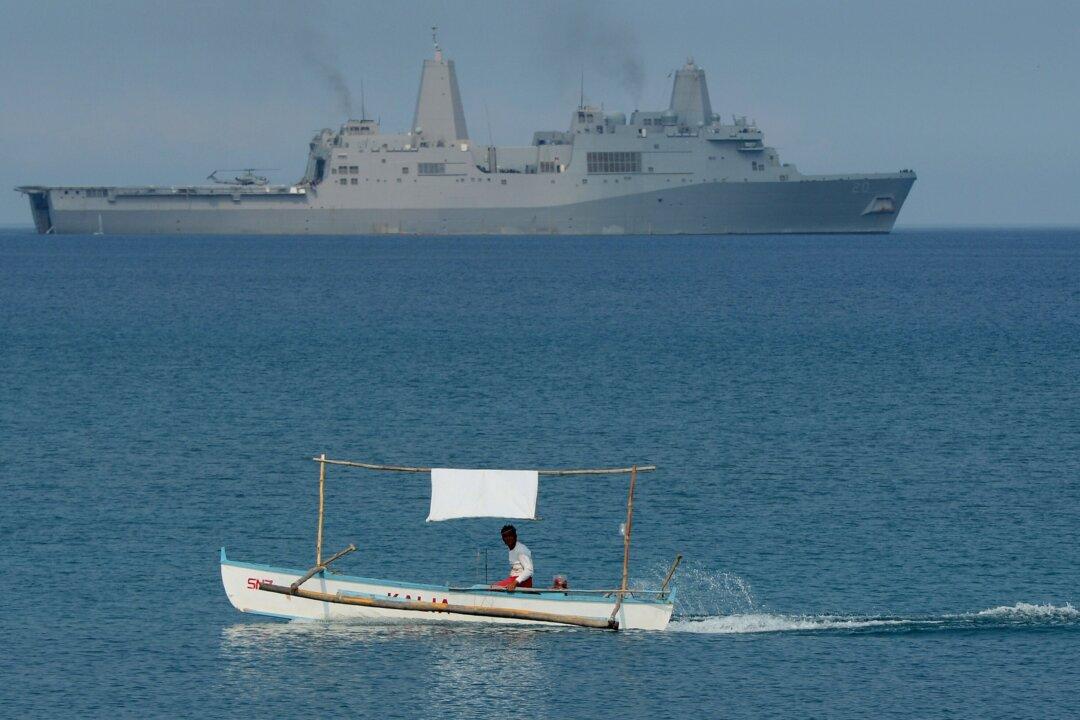

According to Filipino media, the artificial island falls within the Philippines’ 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone.

Prof Ball says China’s behaviour in the South China Sea is provocative, but “in the scale of what we are talking about, that is nothing” compared with conflicts in North-East Asia, where China and Japan are contesting claims over the Tokyo-controlled Senkaku Islands (claimed as the Diaoyus by China).

Of the Senkakus conflict, Prof Ball says: “We are talking about actual footsteps towards nuclear war – submarines and missiles.”

Chinese and Japanese activity in the Senkakus region has escalated to the point where sometimes there are “at least 40 aircraft jostling” over the contested area, he said.

Alarm bells were set off near the Senkakus in January last year when a Chinese military vessel trained its fire-control radar on a Japanese naval destroyer. The incident spurred the Japanese Defense Ministry to go public about that event and reveal another incident from a few days prior, when a Chinese frigate directed fire-control radar at a Japanese military helicopter.

Fire-control radars are not like surveillance or early warning radars – they have one purpose and that is to lock onto a target in order to fire a missile. “Someone does that to us, we fire back,” Prof Ball said.

Counter Measures Needed

Prof Ball is recognised for encouraging openness and transparency, and for his advocacy of multilateral institutions. He has been called one of the region’s “most energetic and activist leaders in establishing forums for security dialogue and measures for building confidence”.

In his experience visiting China over the years, however, Prof Ball says gaining open dialogue and transparency with Chinese military leaders is difficult. He recounted a private meeting with a Chinese admiral shortly after the fire-control radar incident. Prof Ball had seen direct evidence of the encounter – “tapes of the radar frequencies, the pulse rates and the pulse repetition frequencies” – and wanted to know what had happened on the Chinese side and why it took place.

“In a private meeting, I asked the admiral why ... and he denied it to my face,” Prof Ball said. The Chinese admiral would not even concede that an incident had happened.

“I don’t see the point of this sort of dialogue,” he added.

With so many players in the region and few barriers against conflict escalation, the North-East Asian nuclear arms race is now far more complex and dangerous than the Cold War, he says.

In the Cold War, there were mechanisms at each level of potential confrontation, including a direct hotline between the US and Soviet leaders.

“Once things get serious here, [there is] nothing to slow things down. On the contrary, you have all the incentives to go first,” he said.

As a key ally to Japan and South Korea, the United States would ultimately be involved in any escalated conflict and could play a decisive role in the region. While Prof Ball believes it is too late for arms control mechanisms, he says it is critical that Washington ensures policy development and informed debate.

He says there need to be counter measures and counter counter measures developed for each level of escalation – and fast. “Given the high potential for things to go seriously wrong, we need to do all we can to put in place processes to dampen and slow things down,” said Prof Ball.

Professor Desmond Ball has authored and edited over 60 publications on defence and nuclear strategy. He was instrumental in setting up regional bodies such as the Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia-Pacific - a forerunner to the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) - and was described by Kim Beazley, former leader of the Australian Labor Party and now Australia’s ambassador to the United States, as “a national asset” for his contribution to Australian national security policy.

Professor Ball is also well known in the United States. Following research positions at Columbia and Harvard universities, he worked with former US president Jimmy Carter and former US Secretary of State Robert McNamara and advised the US against nuclear escalation in the 1970s.