Sidney Perkowitz, a physics professor at Emory University, explains why we’re closer than most people think to sending astronauts to Mars and how it might be possible to use the planet’s raw materials to survive:

Like any long-distance relationship, our love affair with Mars has had its ups and downs. The planet’s red tint made it a distinctive—but ominous—nighttime presence to the ancients, who gazed at it with the naked eye. Later we got closer views through telescopes, but the planet still remained a mystery, ripe for speculation.

A century ago, the American astronomer Percival Lowell mistakenly interpreted Martian surface features as canals that intelligent beings had built to distribute water across a dry world. This was just one example in a long history of imagining life on Mars, from H G Wells portraying Martians as bloodthirsty invaders of Earth, to Edgar Rice Burroughs, Kim Stanley Robinson, and others wondering how we could visit Mars and meet the Martians.

The latest entry in this long tradition is the sci-fi flick The Martian, to be released on October 2 (watch the movie trailer). Directed by Ridley Scott and based on Andy Weir’s self-published novel, it tells the story of an astronaut (played by Matt Damon) stranded on Mars. Both book and movie try to be as true to the science as possible—and, in fact, the science and the fiction around missions to Mars are rapidly converging.

NASA’s Curiosity rover and other instruments have shown that Mars once had oceans of liquid water, a tantalizing hint that life was once present.

And now NASA has just reported the electrifying news that liquid water is flowing on Mars.

This discovery increases the odds that there is currently life on Mars—picture microbes, not little green men—while heightening interest in NASA’s proposal to send astronauts there by the 2030s as the next great exploration of space and alien life.

‘First We Have to Get There’

So how close are we to actually sending people to Mars and having them survive on an inhospitable planet? First we have to get there.

Making it to Mars won’t be easy. It’s the next planet out from the sun, but a daunting 140 million miles away from us, on average—far beyond the Earth’s moon, which, at nearly 250,000 miles away, is the only other celestial body human beings have set foot on.

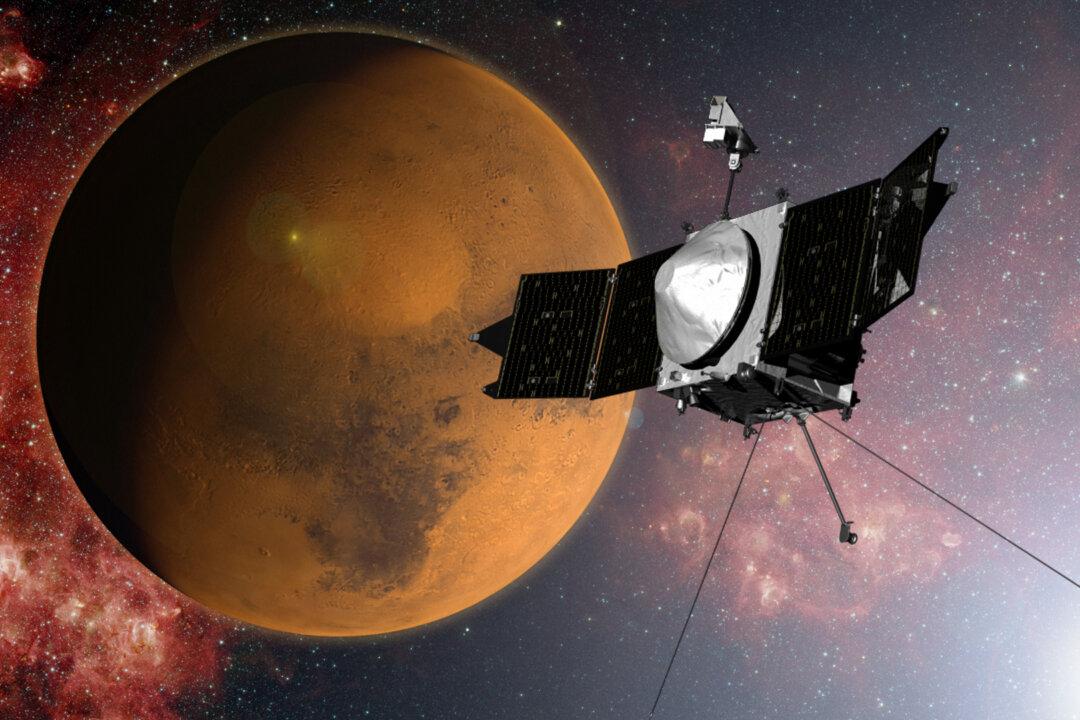

Nevertheless, NASA and several private ventures believe that by further developing existing propulsion methods, they can send a manned spacecraft to Mars.

One NASA scenario would, over several years, pre-position supplies on the Martian moon Phobos, shipped there by unmanned spacecraft; land four astronauts on Phobos after an eight-month trip from Earth; and ferry them and their supplies down to Mars for a 10-month stay, before returning the astronauts to Earth.

We know less, though, about how a long voyage inside a cramped metal box would affect crew health and morale. Extended time in space under essentially zero gravity has adverse effects, including loss of bone density and muscle strength, which astronauts experienced after months aboard the International Space Station (ISS).

The Mental Challenges

There are psychological factors, too. ISS astronauts in Earth orbit can see and communicate with their home planet, and could reach it in an escape craft, if necessary. For the isolated Mars team, home would be a distant dot in the sky; contact would be made difficult by the long time lag for radio signals. Even at the closest approach of Mars to the Earth, 36 million miles, nearly seven minutes would go by before anything said over a radio link could receive a response.