CHARLESTON, S.C.—To commission a ship is to invoke a legacy. In the case of the destroyer USS Truxtun, there is also a legacy of heroic altruism. Sailors from the USS Truxtun and the USS Pollux, and villagers from St. Lawrence and Lawn, two towns in Newfoundland and Labrador, the easternmost province of Canada, had a fateful meeting 67 years ago.

Mayor Wade Rowsell of St. Lawrence traveled almost 2,000 miles to the ceremony. “This is a living history story, on the legacy of the Truxtun and the history of the province,” he said.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt wrote a letter to the people of St. Lawrence commending “the magnificent and courageous work rendered, and the sacrifices you made in rescuing and caring for the United States ships grounded on your shores.” The United States gave a hospital to St. Lawrence. The town built a museum and a path with plaques describing the events.

The people of St. Lawrence and Lawn saved the lives of 186 American sailors. The two ships were escorting a supply ship to protect it from submarines. Gale force winds blew, and the ships went off course. They ran aground about two hundred yards from shore and began to leak oil. To fall into the water was to risk death from hypothermia within minutes. It was the middle of the night. The beach ended in ice-covered cliffs.

One sailor made it to land. He cut handholds in the ice with a knife and scaled the cliffs. He roused the villagers. They got ropes and hauled the survivors up the cliffs. They took them into their homes.

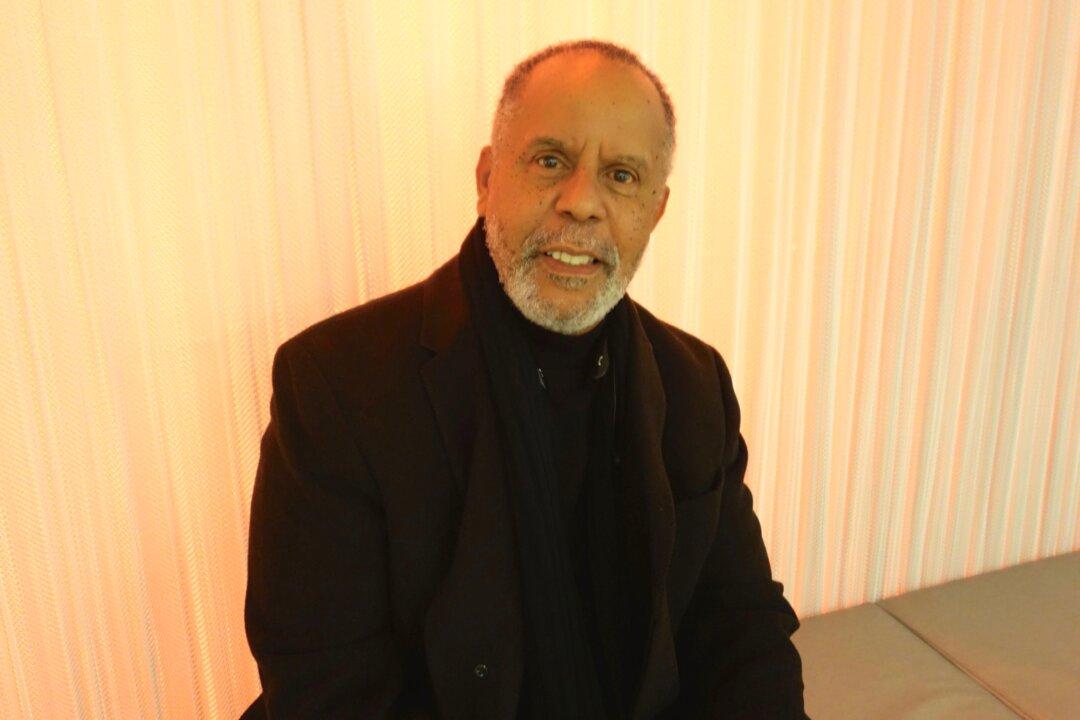

Gus Etchegary was a teenager. “We got as many ropes as we could. We walked to the place, to see what was there from the top. I was given the job by my father of building a fire. The weather was really bad, raging seas.”

A small plane tried to drop a line to the ship, but it could not. A small boat tried to reach the ship but capsized. If the sailors clinging to the wreckage did jump into the sea, “there was a big undertow. So when they jumped and tried to swim, it was not a good result,” said Mr. Etchegary.