Many international friends of Great Britain hope that after 43 years of EU membership, some democratically legitimate way to reverse the consultative Brexit vote result taken last June 23 can be found, presumably through a new binding referendum. Some of the 17 million who voted for Brexit appear to have had second thoughts; an online petition calling for a second vote has more than three million signatories.

David Vines, a professor of economics at Oxford, has a four-part action plan for those who would like to see the stay option remain open. He says the June vote was mostly a vote against economic policy in which inequality of outcomes and opportunity widened radically.

Vines thinks austerity since 2008 “inflicted significant costs on those who are not well-off, while the rich got off scot-free. Concentration of opportunity in London and labour market deregulation hit the less well-off hard. They had to compete with skilled and entrepreneurial migrants from Eastern Europe. The Leave vote was a consequence of this fact.” His four points are as follows.

End Austerity

The U.K. needs a “New Deal” in macroeconomic policy akin to President Roosevelt’s New Deal of 1933. In 1945, the U.K. Labour government offered a similar program around the Beveridge Welfare State and National Health. An example of what could be done now is a second divided highway connecting Scotland with England.

Impose Restrictions on Movement of Labour

Changing the treatment of migration might make it possible to avoid a conflict with the EU’s principle of the free movement of labour. Citizens of EU countries are entitled to look for a job in another EU country, work there without needing a work permit, reside there for that purpose, stay there even after employment has finished, and enjoy equal treatment with nationals in access to employment, working conditions, and other social and tax advantages.

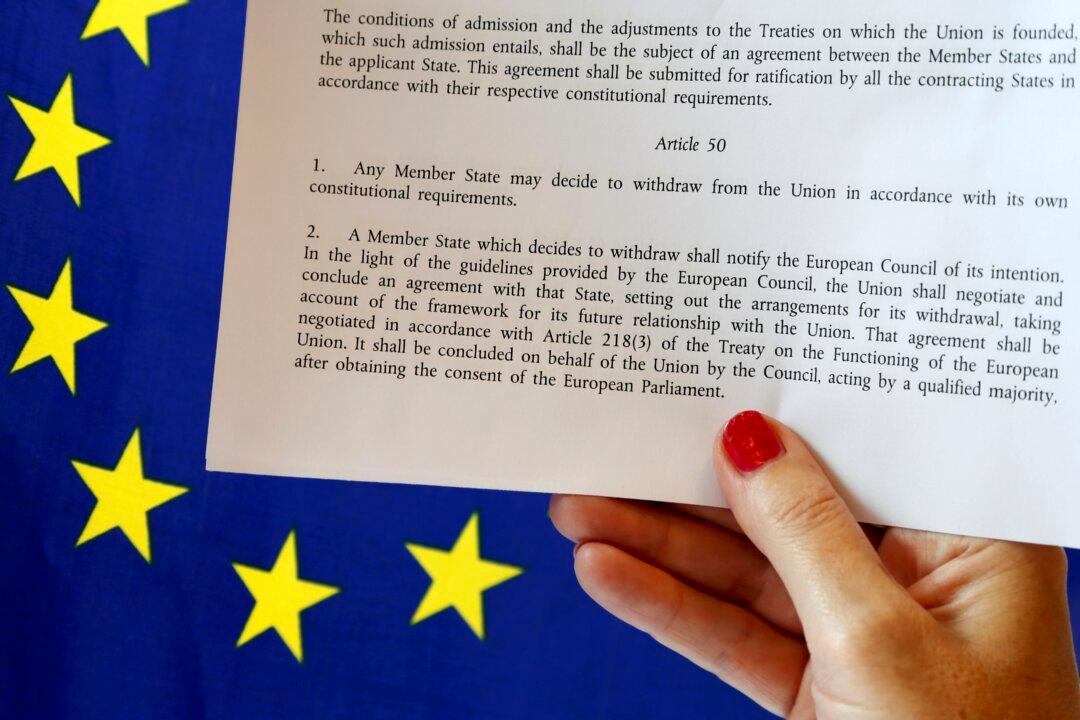

A safeguard clause in the treaty authorizes a member state to re-introduce restrictions on the free movement of labour in the context of a “serious labour market disturbance.” This serves to move the principle of freedom of movement from an absolute right to a conditional right, dependent on particular circumstances.