Andy Weir, the author of the 2011 novel on which the new film “The Martian” is based, strove for realism in his fictional world; everything from the type of plant life that could grow on the red planet’s arid crust to its gravity (one-third of Earth’s) was based on up-to-date science.

But Weir had to depart from the realm of fact to that of speculation when deciding when the story would take place: He picked Nov. 7, 2035, as the day that NASA’s seven-man crew would land on Mars.

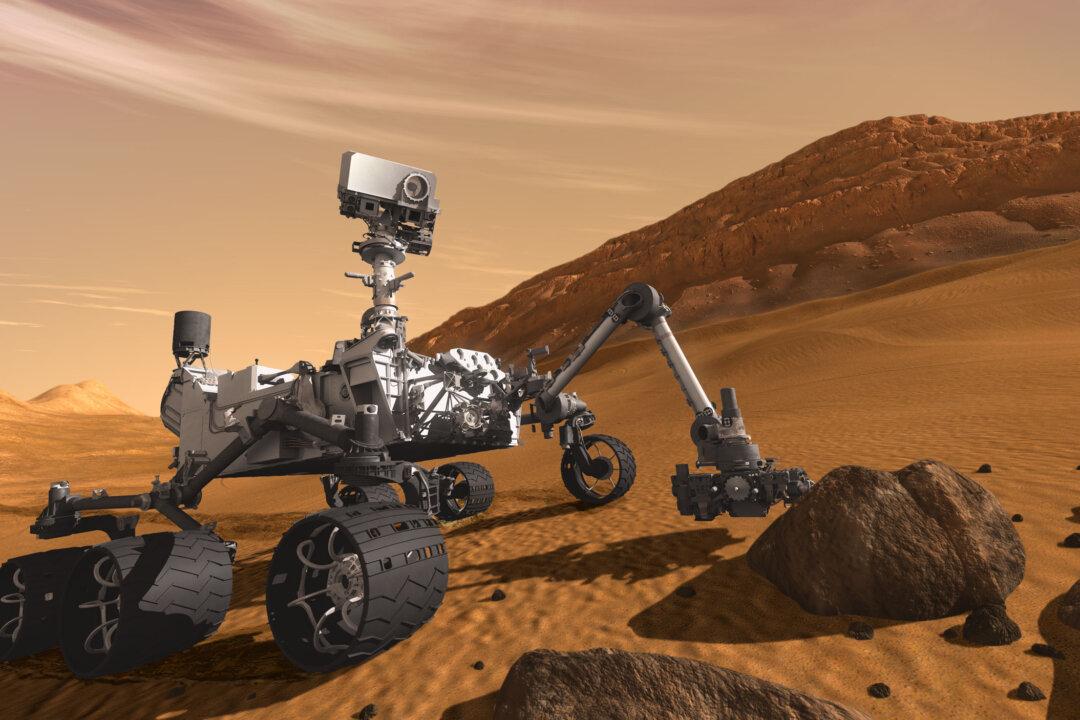

The reality is, a manned mission to Mars requires overcoming a wide range of technological hurdles, as well as ethical and financial problems.