They marched down Pennsylvania Avenue, 65,000 strong, tightly packed, in a column that ultimately stretched for 15 miles and took over six hours to pass.

Their “glittering muskets looked like a solid mass of steel, moving with the regularity of a pendulum.”

Sherman’s Army marched steadily, firmly, like the hardened veterans that they were, with dignity and discipline.

They marched through throngs of cheering spectators, thousands upon thousands of black and white Washingtonians, crowding the streets and the sidewalks, leaning out of windows and huzzahing.

Their torn and dirty flags were garlanded with flowers, but black streamers hung from the staffs, emblems of mourning for Abraham Lincoln.

The Army of the Potomac had marched the day before, all spit and polish, to great cheers of acclamation, but this day, May 24, 1865, belonged to the Western Army, to Sherman’s Bummers. “Bummer” had once been used as an epithet for slackers and thieves, but Sherman’s men took this on as an honored nickname.

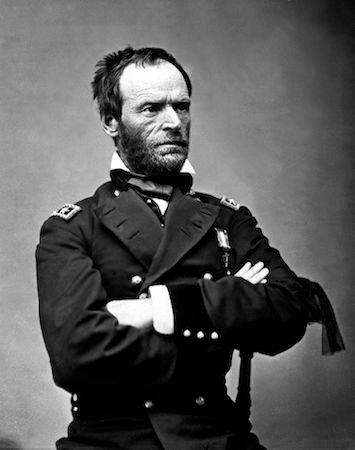

They were, in the words of the New York Times, the “glorious veterans … heroes of the greatest march on record,” and their beloved Uncle Billy, Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, was the man of the hour.

The Spoils of War

Spectators uniformly noted that the cheers for the Westerners were even louder and more sustained than those for the Easterners.

Nor did they march alone. Sherman’s Army, famous for making Georgia—and then South Carolina and North Carolina—howl, brought their spoils of war to the victory parade.

Each brigade was led by its respective “pioneer corps,” made up of formerly enslaved men who were put to work clearing swamps and building roads, helping the soldiers as they hacked their way across the Confederacy.

And interspersed throughout the columns of soldiers were scenes designed to bring the story of the march right into the heart of the capital: African-American mothers with their children; mules and donkeys laden down with hams and chickens; soldiers’ pet dogs and raccoons.

The crowd responded to these amusing vignettes with further cheers and gales of laughter.

The Beginning of Remembering

The Grand Review of the Union Armies on May 23–24 1865, was a performance, a victory display of martial power designed to put the final punctuation on the war.

Washingtonians literally swept away the mourning crepe that had draped buildings for the previous five weeks, and greeted the soldiers with open arms and an outpouring of emotion.

Sherman was himself a master of the theatrical grand gesture, as evidenced by the drama of his march, and he embraced this opportunity.