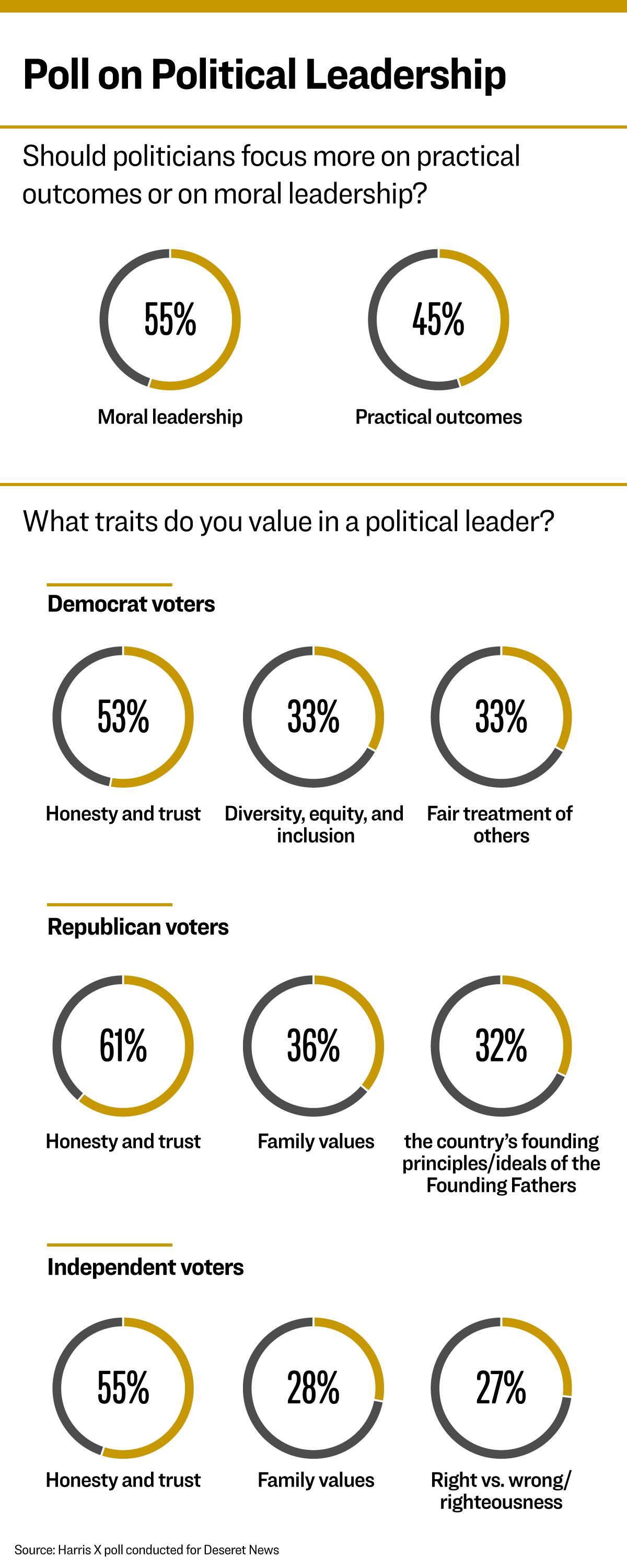

A national poll conducted by Harris X in the summer of 2023 found that a majority of Americans thought that politicians should focus more on moral leadership than on practical outcomes. When asked a second question “What do you most closely associate with moral leadership?” a majority of Democrats, Republicans, and Independents selected trust and honesty for the top of the list.

Illustration by The Epoch Times, Getty Images, Shutterstock