This week and last in Rio de Janeiro, more than 11,000 athletes from 206 countries are participating in the Summer Olympics—306 events in 28 sports. At press time, the United States leads with 26 gold medals, but Usain Bolt of Jamaica probably eclipsed everyone with his 100-meter win over the weekend.

Last March, the International Olympic Committee announced the Refugee Olympic Athletes initiative, created to act as a symbol of hope and to bring global attention to the magnitude of the refugee crisis.

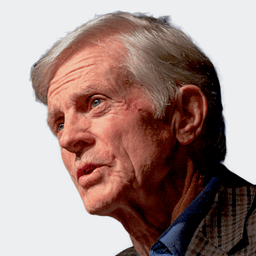

Jamaica's Usain Bolt looks to Canada's Andre De Grasse after crossing the line during a men's 100-meter semifinal at the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro on Aug. 14. AP Photo/Matt Slocum