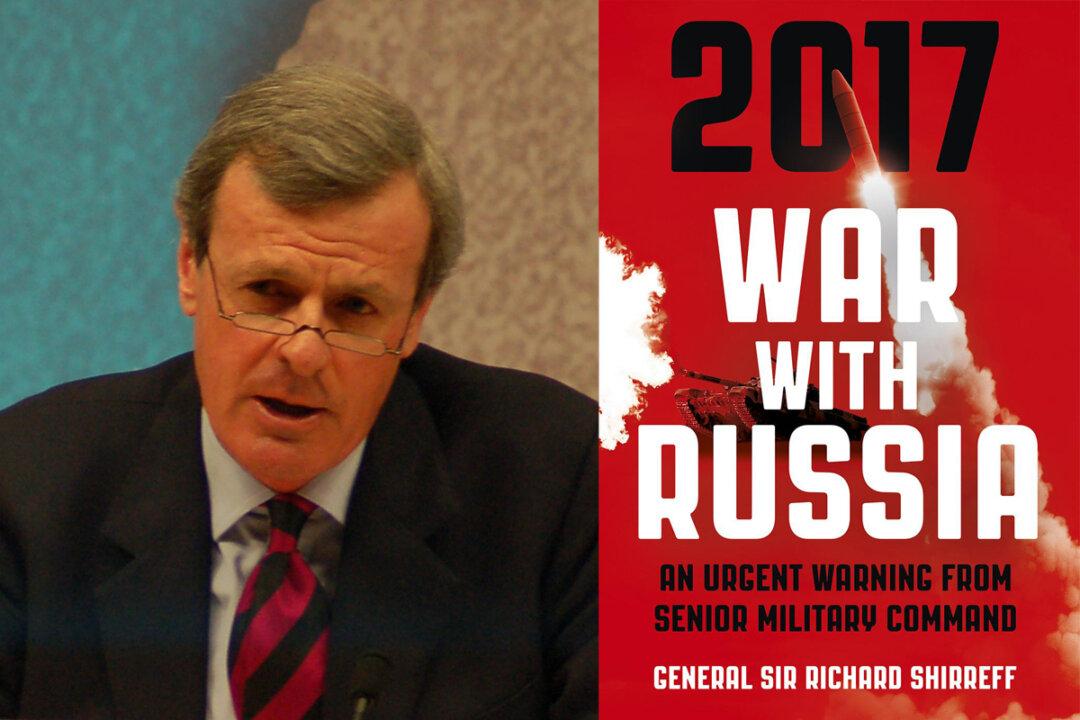

A new book by General Sir Richard Shirreff, NATO’s deputy supreme allied commander for Europe (2011–2014), evokes a potential scenario that leads to a devastating future war with Russia.

The book, “2017 War With Russia,” is clearly labelled as a work of fiction. But it portrays a fairly convincing manufactured incident that the fictional president of Russia uses as a causus belli for a clash with NATO. In his account, Russia rapidly expands its war aims by invading the Baltic States, which are NATO members, and world war ensues. Perhaps more worryingly, the author has since told BBC Radio 4’s Today program that such a conflict is “entirely plausible.”

Fact vs Fiction

I do not want to give any more away about the book (it is a good and authentic, if gloomy, read). But the general’s underlying political message—clearly articulated in the book’s preface—is that the hollowing out of defense capabilities across the West and its reluctance and inability to stand up to Russia is making war ever more likely. Is this an accurate assessment of the real world?

The novel is reminiscent of Tom Clancy’s “The Hunt for Red October“ and the excellent ”The Third World War: August 1985“ by General John Hackett. The latter, written at the height of the Cold War, was conceived as a ”future history,” supposedly looking back at the outbreak and subsequent unfolding of a full-blown NATO vs Warsaw Pact war.