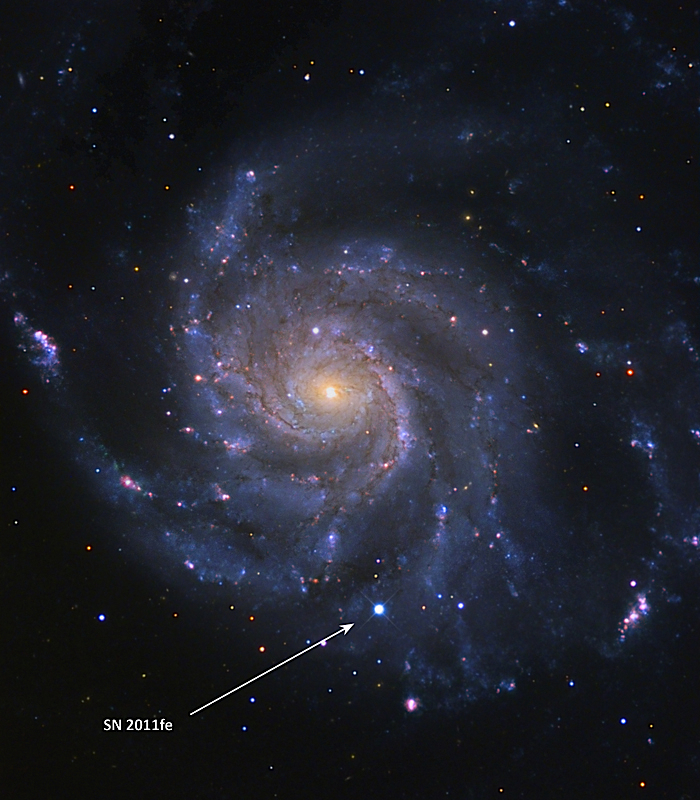

The detonation mechanism of Type Ia supernovae has been further elucidated following observations of a parent system spotted blowing up in the Pinwheel Galaxy in August.

Named SN 2011fe, the explosion happened around 21 million light-years away, and is the nearest known Type Ia supernova since 1986.

These supernovae are unusually bright, and are used by astronomers as “standard candles” to measure cosmic distances, and also the expansion rate of the universe due to dark energy.

“We caught the supernova just 11 hours after it exploded, so soon that we were later able to calculate the actual moment of the explosion to within 20 minutes,” said study co-author Peter Nugent at the University of California, Berkeley in a press release.

“Our early observations confirmed some assumptions about the physics of Type Ia supernovae, and we ruled out a number of possible models,” he added. “But with this close-up look, we also found things nobody had dreamed of.

The international team studied the event closely to learn about the binary system that produced the explosion.

Theoretical models are based on a tiny white dwarf star circling a larger companion from which it absorbs matter until it reaches about 1.4 times our sun’s mass, and collapses into a supernova.

“As it approaches the limit, conditions are met in the center so that the white dwarf detonates in a colossal thermonuclear explosion, which converts the carbon and oxygen to heavier elements including nickel,” Nugent explained.

“A shock wave rips through it and ejects the material in a bright expanding photosphere,” he continued. “Much of the brightness comes from the heat of the radioactive nickel as it decays to cobalt.”

The astronomers looked at how the supernova’s brightness evolved to place an upper limit on the size of the parent star before it exploded.

“We made an absurdly conservative assumption that the earliest luminosity was due entirely to the explosion itself and would increase over time in proportion to the size of the expanding fireball, which set an upper limit on the radius of the progenitor,” Nugent said.

The shock wave rips the star apart in a matter of seconds, but the heated debris from the explosion glows for several hours. Its brightness is determined by the star’s size.

“Sure enough, it could only have been a white dwarf,” Nugent said. “The spectra gave us the carbon and oxygen, so we knew we had the first direct evidence that a Type Ia supernova does indeed start with a carbon-oxygen white dwarf.”

The team discounted various potential progenitors, including a dying red giant star, which would have generated a much brighter explosion. They calculated that the companion was a main-sequence star like our sun.

The detonation revealed some unusual observations with many intermediate-mass elements emitted, such as ionized oxygen, magnesium, and iron, moving at 16,000 kilometers per second (9,940 miles per second) or over 5 percent the speed of light. However, some of the oxygen was moving much faster, at more than 20,000 kilometers per second (12,400 miles per second).

“The high-velocity oxygen shows that the oxygen wasn’t evenly distributed when the white dwarf blew up, indicating unusual clumpiness in the way it was dispersed,” Nugent explained.

The supernova also underwent considerable mixing with traces of radioactive nickel present right through to the outer photosphere, meaning its brightness was almost exactly related to the explosion’s expanding surface.

“Understanding how these giant explosions create and mix materials is important because supernovae are where we get most of the elements that make up the Earth and even our own bodies–for instance, these supernovae are a major source of iron in the universe,” said Mark Sullivan at the University of Oxford in the release.

“So we are all made of bits of exploding stars.”

The findings were published in the journal Nature on Dec. 15.