NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has discovered a group of unusual stars called “blue stragglers” for the first time within the core of our own Milky Way.

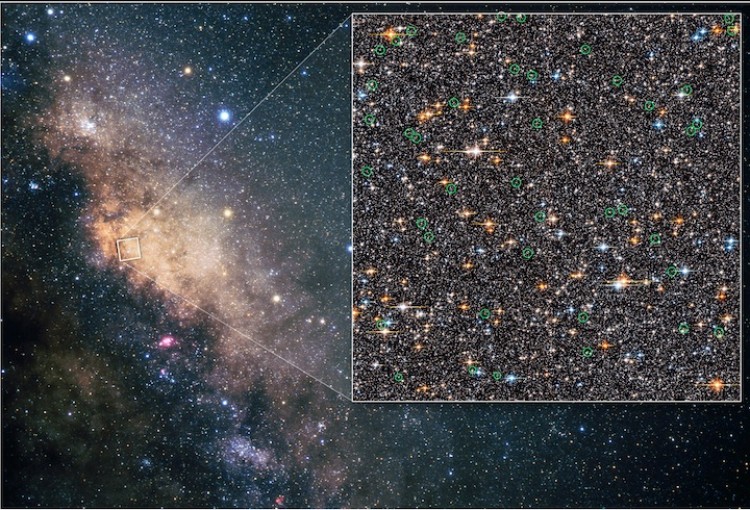

These luminous blue stars are hotter, larger and age more slowly than other stars in their cluster. It was suspected such a group of stars lives in our galaxy’s bulge, 26,000 light years away. However, younger stars obscured the view until Hubble made a 2006 survey called the Sagittarius Window Eclipsing Extrasolar Planet Search (SWEEPS).

The telescope gathered data on 180,000 stars in our galaxy’s packed center, made a return trip two years later to compare their motion, and detected 42 blue straggler candidates.

“The size of the field of view on the sky is roughly that of the thickness of a human fingernail held at arm’s length, and within this region, Hubble sees about a quarter million stars toward the bulge,” said lead author Will Clarkson at Indiana University, Bloomington in a NASA press release.

“Only the superb image quality and stability of Hubble allowed us to make this measurement in such a crowded field.”

The team of astronomers think 18 to 37 of the stars are actually blue stragglers, while the others could be a small cluster of young bulge stars or simply foreground objects.

“Although the Milky Way bulge is by far the closest galaxy bulge, several key aspects of its formation and subsequent evolution remain poorly understood,” Clarkson said. “Many details of its star formation history remain controversial. The extent of the blue straggler population detected provides two new constraints for models of the star formation history of the bulge.”

Exactly how blue stragglers form remains unclear. One possible mechanism is that they may collide with neighboring stars and steal their mass, becoming hotter and bluer.

The findings will be published in The Astrophysical Journal.

These luminous blue stars are hotter, larger and age more slowly than other stars in their cluster. It was suspected such a group of stars lives in our galaxy’s bulge, 26,000 light years away. However, younger stars obscured the view until Hubble made a 2006 survey called the Sagittarius Window Eclipsing Extrasolar Planet Search (SWEEPS).

The telescope gathered data on 180,000 stars in our galaxy’s packed center, made a return trip two years later to compare their motion, and detected 42 blue straggler candidates.

“The size of the field of view on the sky is roughly that of the thickness of a human fingernail held at arm’s length, and within this region, Hubble sees about a quarter million stars toward the bulge,” said lead author Will Clarkson at Indiana University, Bloomington in a NASA press release.

“Only the superb image quality and stability of Hubble allowed us to make this measurement in such a crowded field.”

The team of astronomers think 18 to 37 of the stars are actually blue stragglers, while the others could be a small cluster of young bulge stars or simply foreground objects.

“Although the Milky Way bulge is by far the closest galaxy bulge, several key aspects of its formation and subsequent evolution remain poorly understood,” Clarkson said. “Many details of its star formation history remain controversial. The extent of the blue straggler population detected provides two new constraints for models of the star formation history of the bulge.”

Exactly how blue stragglers form remains unclear. One possible mechanism is that they may collide with neighboring stars and steal their mass, becoming hotter and bluer.

The findings will be published in The Astrophysical Journal.