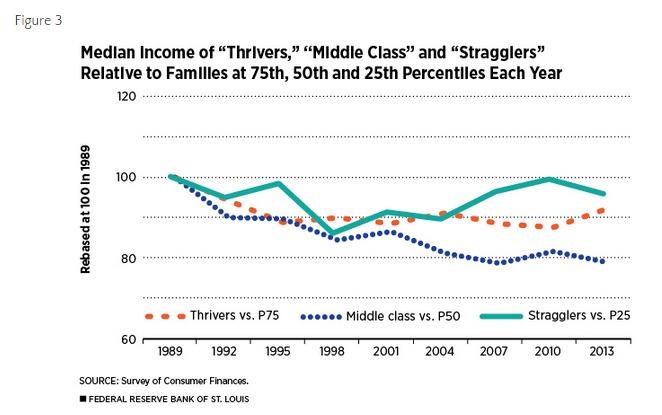

Everybody knows that the “median” American household or the middle class isn’t faring too well. Unfortunately, a new study redefined the term middle class and it’s even worse than we thought.

“Purely income- or wealth-based definitions of the middle class are ambiguous and unstable. It tells us nothing about the characteristics of the median family or any other family at that moment or over time,” states a report by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Instead of taking the median household income (the exact middle of the spectrum, not a simple average), which has been declining since 1999, the study defines its middle class as a household headed by somebody who is 40 years or older, white or Asian, and has at least a high-school diploma. Blacks or Hispanics need at least a two-year college degree to make the bracket.