As the debate rages on in Alberta about how to manage a dangerous stretch of highway leading to the Fort McMurray oil sands, critics say charging tolls would not be an effective solution.

Albertans have called for increased urgency in twinning Highway 63 after seven people, including two children and a woman who was six months pregnant, died April 27 in a head-on crash.

Dubbed “Hell’s Highway” or “Highway of Death,” 63 is a busy 240-kilometre single-lane stretch of highway running north of Edmonton to Fort McMurray—the only all-weather highway serving the booming oil sands region.

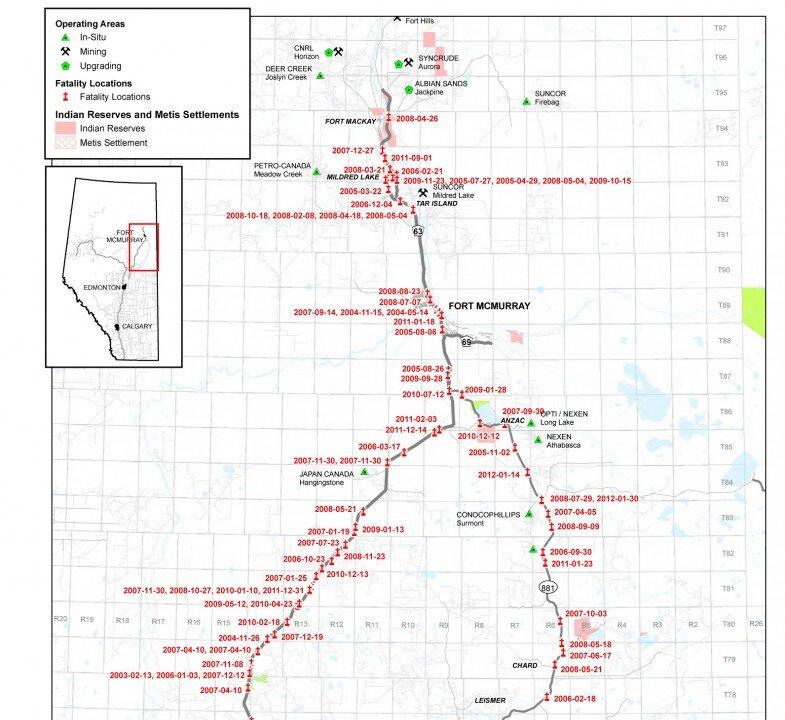

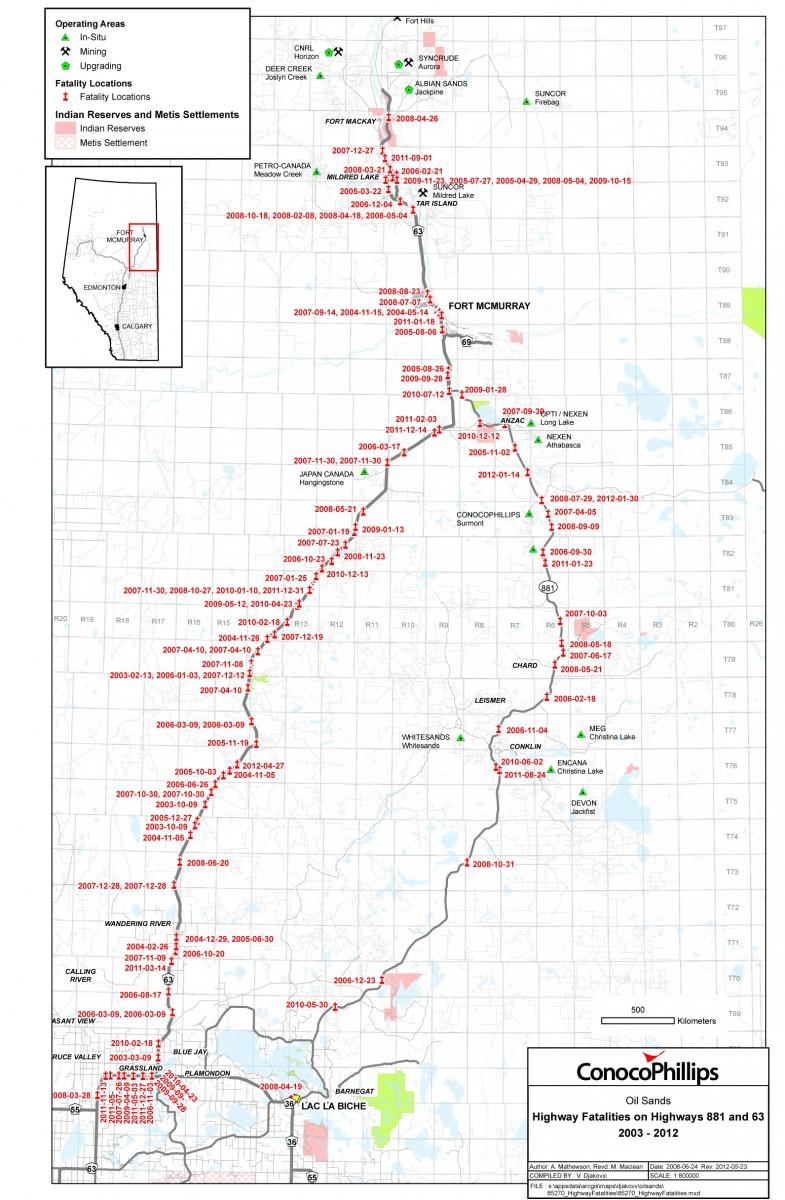

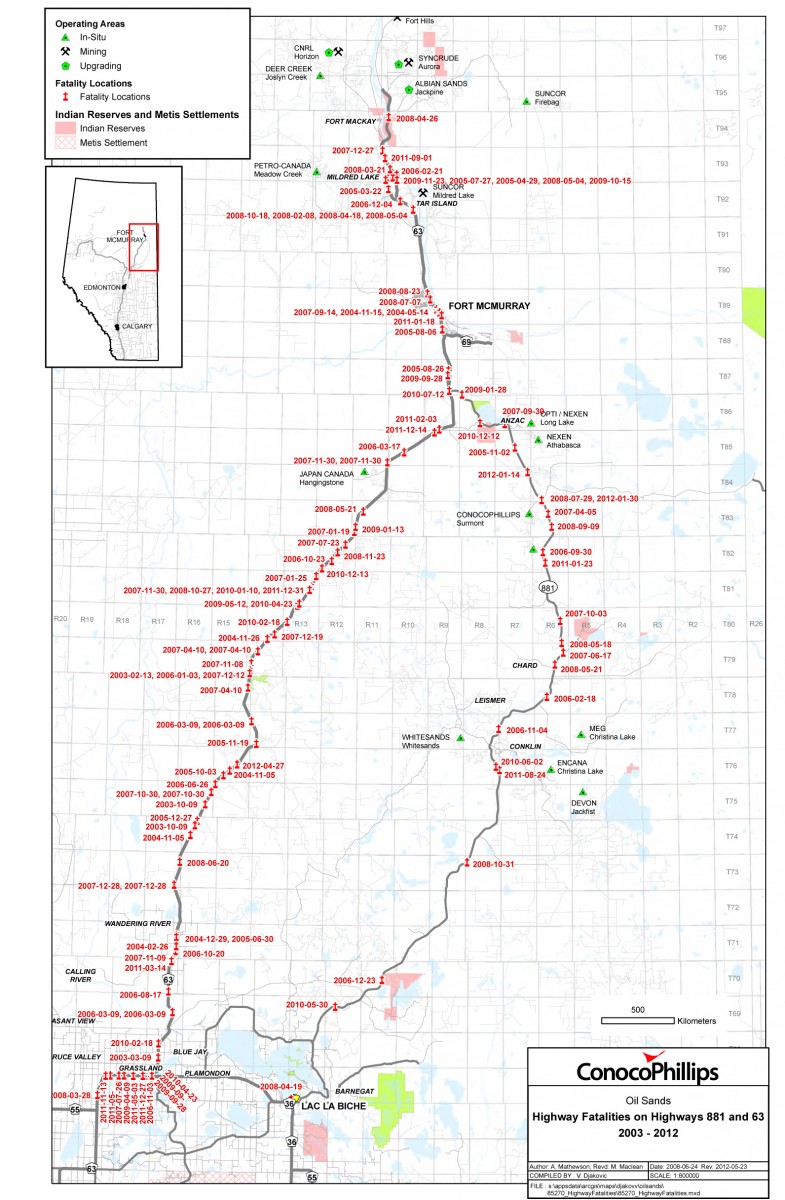

There have been more than 1,000 collisions on the highway in the past decade, with 46 fatalities since 2006.

Traffic has exploded on the remote highway in recent years as oil sands development in the area has rapidly increased. Heavy industrial traffic is commonplace, leading to road congestion and dangerous passing conditions.

Nicole Auser is one of the main forces behind Twin63Now.ca, a website that advocates for twinning the highway, and has helped to organize a number of public protests on the issue.

A lifelong Fort McMurray resident, Auser believes the only way to reduce deaths on the road is to twin it.

“Some things can’t be changed, like wildlife and weather you can’t control, but twinning the highway you can. Drivers—you can kind of control them to an extent, but all the efforts that have been made so far have made very little difference,” she said.

Premier Alison Redford suggested recently that tolls were being discussed as a potential way to raise money for the expected $1 billion cost of twinning the highway.

But Auser says tolling the highway would lead to resentment among local residents, and ultimately prolong the twinning because it would take decades to raise the required $1 billion.

“If you do the math, even over five years, the amount of money that a tollbooth would generate would not even make up a significant fraction of the cost of twinning this highway. So it doesn’t really make much sense from a financial standpoint.”

In May, Redford appointed Fort McMurray-Wood Buffalo MLA Mike Allen as a “special advisor” to assist the Minister of Transportation Ric McIver in finding a solution to Highway 63. Part of Allen’s responsibility will be to deliver a report on how to accelerate the twinning.

Allen, whose report is expected by June 29, has said a toll road to Fort McMurray would be expensive, unpopular with both residents and industry, and estimates it could take 30 years to raise enough money to pay for the twinning.

He also said the tolls have not been ruled out, however, because the province has vowed to consider all feasible options in speeding up the twinning.

‘We need action’

The Official Opposition Wildrose party has criticized Redford for naming Allen as an advisor on the issue, calling the move a substitute for “real action.”

“It’s shocking that the local MLA needs to be promoted to ‘Special Advisor’ for the constituents of Fort McMurray to have their voice heard at the Legislature,” Wildrose MLA Shan Saskiw said in a statement.

“This government’s record on Highway 63 consists entirely of empty words and broken promises. We need action, not new job titles for local MLAs.”

The government committed to twinning the Highway in 2006 under former Premier Ralph Klein. Since then only 19 kilometres south of Fort McMurray have been twinned, although it was supposed to be entirely completed in five years.

About 185 kilometres still need to be twinned, much of it through difficult terrain, parkland, muskeg, and boreal forest.

Auser says she has watched the highway evolve from a relatively quiet and pleasant drive to a harrowing and dangerous thoroughfare.

“It’s the amount of industrial traffic and wide loads that makes it stressful. I’ve been stuck behind wide-loads before for an hour or two where they’re too big to pass,” she says.

“It’s not a very nice drive and it should have been twinned a long time ago.”

Auser says Fort McMurray residents have struggled to cope with the loss of life on the highway, which has claimed the lives of local friends, family, and community leaders.

“At first were just really sad about these deaths on the highway—as all of us are anytime anyone dies on a highway—but from here really I think it’s been a wave of emotions. It’s been anger that there’s been no progress, and confusion over a lot of the mixed messages we’re hearing from the government,” she says.

“It’s been apathy in our government too. I know many of us have lost faith in the promises that the government has given us.”

An estimated 10,000 vehicles travel the northern highway every day.

The Epoch Times publishes in 35 countries and in 19 languages. Subscribe to our e-newsletter.