It was an epic battle, one of Canada’s greatest war victories which arguably helped secure democratic freedom for South Korea, yet it remains largely unknown.

This week marks the 63rd anniversary of the Battle of Kapyong, a brilliant defence fought by a single Canadian battalion against thousands of invading Chinese communist troops during the Korean War.

John Bishop was a soldier in the 2nd Battalion of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (2 PPCLI) in the 1951 battle. Although they were outnumbered by about seven to one, fear was not something he experienced during the intense three-day battle, he recalls.

“I don’t remember ever being [afraid]. I think we accepted that we could die and that was part of our job,” said Bishop, 83, president of the Korea Veterans Association and author of “The King’s Bishop,” a book about the battle.

“We were convinced that we were doing a great service,” he said, adding that his team’s sergeant was the famed Tommy Prince, one of Canada’s most decorated First Nations soldiers who served in both World War II and the Korean War.

On the night of April 22, 1951, about 5,000 Chinese troops pushed toward Kapyong Valley, a key route 40 km from the South Korean capital of Seoul, which they hoped to re-capture. The Chinese had joined North Korean forces a year earlier with the aim of taking South Korea, and now led the aggressive spring offensive.

As Bishop and his infantrymen dug trenches along Hill 677 near the valley, they didn’t expect to be on the front lines. The Canadians were prepared for little more than carrying out garrison duty—after all, there were U.N. and South Korean forces stationed on the front 20 km away.

But as the Chinese continued their onslaught the Canadians began to hear rumours of the front’s collapse. By mid-afternoon on April 23, hoards of American and South Korean troops were fleeing past them. By that evening, 2 PPCLI and an Australian battalion positioned nearby were the only ones left to fight.

“We didn’t know it was going to be a big battle until we moved up into position and the Korean army and the American army were withdrawing all around,” recalls Bishop.

Just after midnight the Chinese stepped up their attack, launching relentless waves of artillery, mortar, machine gun fire, and grenades. The Australians bore the brunt of the initial attack but were forced to withdraw on April 24 after running low on ammunition.

Last Battalion Standing

The 700 Canadians on Hill 677 were the last hope of repelling the thousands of remaining Chinese.

“We were in a situation where we had to fight. In fact, we were the last battalion standing—everything had collapsed around us,” says Bishop.

A corporal barely 20 years old at the time, he remembers thinking: “Damn it, if we are in a big battle let’s do our job, and let’s be proud of ourselves.”

The heavy, close-combat fighting raged all night with the Canadians relentlessly defending their position. At one point they even called in a risky artillery strike on their own location to take out the communist soldiers amongst them.

Remarkably, the Chinese assault collapsed by the afternoon of April 25—they were running out of ammunition and had suffered almost 2,000 casualties. The Canadians lost only 10 men, with 23 wounded. Meanwhile, U.N. forces regrouped and came to relieve the exhausted battalion.

Kapyong was the last major offensive by the Chinese, and the battle is recognized as a turning point in the Korean War.

Military historians have attributed the Canadian troops’ remarkable success to collective battle experience, skilled veteran commanding officers, excellent training, good physical condition, and high morale.

Although the Chinese had far greater numbers, they were geographically disadvantaged, having to enter Hill 677 through valleys and approaches below walls of weaponry. They had also outdistanced their supply lines and morale was low due to heavy casualties.

The 2 PPCLI was awarded a United States Presidential Unit Citation for their heroism and exceptional performance—the first of just two Canadian units to ever receive the prestigious award. The Australian battalion also received the award.

The Korean War was initially a peacekeeping mission and only later became recognized as a war. In the fight to keep South Korea free of the grip of communism, 516 Canadians were killed and 1,558 wounded.

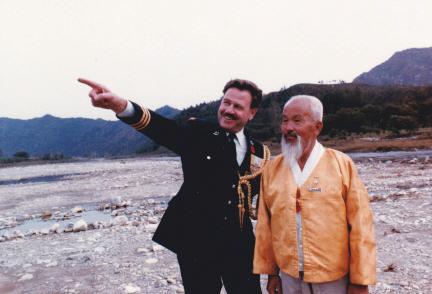

Every year, Bishop marks the anniversary of the Battle of Kapyong at the Kapyong memorial in Pacific Rim National Park on the west coast of Vancouver Island. He also led veterans’ tours to the Kapyong battlefield in Korea until government funding was cut.

Always humble, Bishop says he doesn’t get emotional when he marks the anniversary because he was simply doing his duty. “We did our job, and that’s the big thing.”