Lhasa’s weather in March 2008 was slightly colder than previous years. It was almost March 10 again, which the Chinese communist government refers to as the “1959 Tibetan Uprising” or “1959 Tibetan Rebellion”, but the Tibetans refer to as the Tibetans’ “doom day” or “day of exile.” It has been 49 years since March 10, 1959.

After the large-scale “turmoil” in Lhasa at the end of the 80’s, Lhasa had been fairly stabile for the past twenty years. Organized street protests have been rare. Lhasa gradually became the image of “prosperity and harmony” which the Chinese communist government felt comfortable with.

In March this year, Lhasa remained very quiet. The Tibetans on the streets or visiting temples was smaller than Chinese New Year, because the number who returned home for the Chinese New Year had not returned to Lhasa. But the number of tourists was increasing because the tourism season begins in March.

The quiet streets made one wonder if the Tibetans in Lhasa had forgotten March 10, 1959. Yet the Chinese communist government’s security measurements have reminded people that they are still very sensitive about the special day. Since March 7, the security was enhanced at the checkpoint in Zhangmu leading to Highway 318 towards Gzhis-ka-rtse.

This is a highway with a speed limit. Normally, drivers have to get out of the car at the checkpoint and hand in a document. Since March 7, the staff at the checkpoint checked each vehicle and asked each driver questions, especially if the driver was a Tibetan. Even the passengers in the car were subjected to the same scrutiny.

In addition, the entire security personnel were replaced. In hindsight, the goal might be to prevent Tibetans from entering Lhasa before March 10.

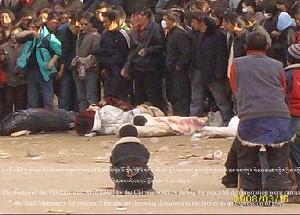

On March 10, Lhasa remained quiet and peaceful as usual until 4 p.m. Over 300 monks left Drepung Monastery for downtown Lhasa, shouting slogans for religious freedom and in opposition to the increases in Han population. They were stopped at Lhasa customs by large numbers of military police. Some monks were arrested and others sat on the ground quietly.

Meanwhile, over 100 monks left the monastery when they heard the news, but were stopped at the foot of the mountain by the military police and kept there until 2 a.m. They beat the monks and drove them back to the monastery. More police, including police in civilian clothes, surrounded on the square of Jokhang Monastery that day.

Many vehicles parked on the borders of the square. Apparently there was a detailed plan for security that day. Most of the vehicles with special license plates belong to the military police. Many of the army or the public security bureau’s vehicles have civilian plates, or even no plate at all. After the protest broke out, the military vehicles and tanks did not have any license plates or had covered them, concealing the identity of the specific troop or military police.

A mid-size bus parked on the border of the square was packed with armed S.W.A.T. police. Until 5 p.m., Lhasa’s old town remained quiet with many shoppers and Tibetans spinning their prayer wheel in hand. When asked if they remember March 10, 1959, Tibetans said that no one will forget that day, but they didn’t plan to make a lot of noise. Instead, they would light up a candle at home and chant scriptures to pray for those victims.