America has come a long way to take action on communist China’s forced organ harvesting on prisoners of conscience, first reported by The Epoch Times over 15 years ago.

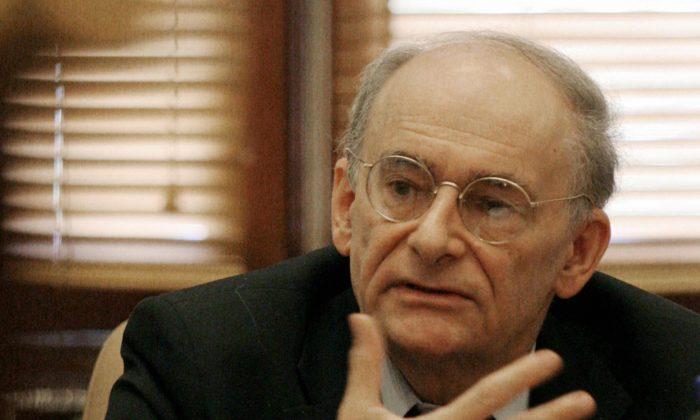

Renowned international human rights lawyer David Matas and the late David Kilgour, a human rights lawyer and a former Canadian member of Parliament, are the pioneers in investigating the matter. Their findings were first released in July 2006.

In March 2006, a Chinese doctor’s wife with the pseudonym of Annie made a public statement in Washington that her ex-husband harvested Falun Gong adherents’ corneas in a hospital in northeast China. Falun Gong, with tenets of truthfulness, compassion, and forbearance, is a spiritual practice subjected to brutal persecution in China since July 1999.

Seeking independent investigation, a nonprofit organization, the Coalition to Investigate the Persecution of Falun Gong, approached Matas, who was used to people going to him about different human rights violations. But, since he couldn’t work on every request, he tried to help by identifying another solution.

However, for this issue, he realized that there was no easy way or obvious alternative to deal with it.

“What I’m told straight up is, ‘If this happens, there are no bodies, and everybody is cremated. There are no autopsies, and there are no witnesses except the perpetrators and victims. Everything happens in a closed environment,’” Matas said. “‘There are no documents except the Chinese hospital and government prison records, which are not accessible. There’s no crime scene. The operating room is immediately cleaned up afterward.’”

He took the case, knowing there would be a lot of work. He said he didn’t start out seeking to prove that Annie was right. Instead, he kept an open mind, thinking he might reach a conclusion rather than leaving the case at a “he said, she said” level, referring to Annie’s and the CCP’s sides of the story.

‘Accumulation of All Evidence’

“The conclusion that Kilgour and I reached was not the result of one particular striking piece of evidence; it was the accumulation of all the evidence that was put together,” said Matas.Several things stood out for them during the investigation.

First, a large group of Falun Gong practitioners didn’t disclose their identities to avoid implicating their families and workplaces. “That was an extremely vulnerable population,” according to Matas.

The Chinese Communist Party had praised Falun Gong for its health benefits after the practice was introduced to the public in 1992. However, in 1999, Falun Gong outnumbered the CCP by 10 to 40 million ahderents. “The Party just got worried about its own popularity in the face of the popularity of Falun Gong, which at the time, wasn’t anti-communist, but was non-communist,” he added. The CCP’s insecurity led to a nationwide persecution launched in July 1999.

In Matas’s view, Falun Gong’s peaceful resistance began with the belief that somehow there had been a mistake. “There had been a misunderstanding because most people were not familiar with the inner dynamics of the Communist Party. You got these protests saying Falun Gong was good, as if the Party had made a mistake and thought it was bad.

“Whereas, in fact, the Party’s problem with Falun Gong was that it was good.”

Initially, many Falun Gong protesters were released upon arrest as their sheer number maxed out the CCP’s detention facilities. However, these adherents later realized that their home environment was victimized due to their protests. Their families and workplaces were harassed and even suffered financial penalties. Therefore, when they protested again, they kept their identities unknown. As a result, their families had no idea of their whereabouts.

Secondly, Matas and Kilgour noticed a pattern of blood tests and organ examinations almost exclusively on Falun Gong adherents. Matas said that when he began his investigation, most of his Falun Gong interviewees didn’t know about forced organ harvesting; they wanted to talk about torture and abuse in China’s labor camps and prisons instead.

Although the adherents didn’t volunteer the blood test information, Matas could extract that and see a pattern.

Thirdly, investigators could call into Chinese hospitals, pretending to be relatives of patients who needed organ transplants. They would ask specifically for “Falun Gong organs” because adherents who meditate are usually healthier than other organ sources, such as death row prisoners. And the answers from doctors were affirmative.

Matas said he was prepared to say, “Maybe [the doctors] are just trying to make a sale. Who knows?” That was a possible explanation of these doctors’ answers in the 2006 recordings.

Yet soon, a 2008 documentary by a TV station majority-owned by the CCP excluded that possibility for Matas.

“We have a recording, interweaving seamlessly in his own voice, the stuff he denies having said, and the stuff he admits having said. I don’t even know if that would’ve been technologically possible, but I knew very well we didn’t do that,” said Matas, adding that the CCP could have denied the whole phone conversation and stated that the doctor was claiming anything to win business.

Yet the CCP didn’t do so, according to Matas, because of its dual problem with two goals that conflicted with each other: promoting the business of organ transplants and denying forced organ harvesting.

“It’s very hard to do both at the same time; talk about what they’re doing publicly, promote it publicly, advertise it publicly, and then say it isn’t happening,” he added. “They leave these evidentiary trails all over the place. It’s only when they see how we’re looking at this and how it shows what they’re doing, then it disappears.”

‘Slow-Moving Genocide’

Matas called the forced organ harvesting against Falun Gong adherents a “slow-moving genocide.”“It’s not everybody being killed all at once or within a short period of time. It’s been stretching out over decades now. It started in 2001, and this is 2023. It’s been going on for 22 years now.” He added that Uyghurs had become an increasing organ source in recent years.

To him, the fact that Falun Gong ahderents can recant the practice to relinquish their Falun Gong identity and be spared from being killed for their organs doesn’t change the genocide nature of the killing. He said this was because the perpetrator controls the definition of the group or the targets of genocide.

He also said profit-making was a partial motive but not the primary driver.

‘Still a Long Way to Go’

Many countries and politicians became well-informed about the issue through the tireless efforts of Matas, Kilgour, and Falun Gong adherents.No extra-territorial legislation was in place to combat organ transplant abuse when Matas and Kilgour first started their work.

Now, 19 countries, including the United States and Canada, have passed extra-territorial legislation that people involved in killing for organs abroad can be prosecuted domestically, according to Matas. “But this is only 19 countries. There are 194 countries, and there’s still a long way to go,” he said.

The treaty has been signed and ratified by 13 member states of the Council of Europe, including Albania, Belgium, Croatia, Czech Republic, Latvia, Malta, Moldova, Montenegro, Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, and Switzerland. One observer state, Costa Rica, has also ratified the Convention. Additionally, Chile, a state that is neither a member nor an observer, has been invited to do so.