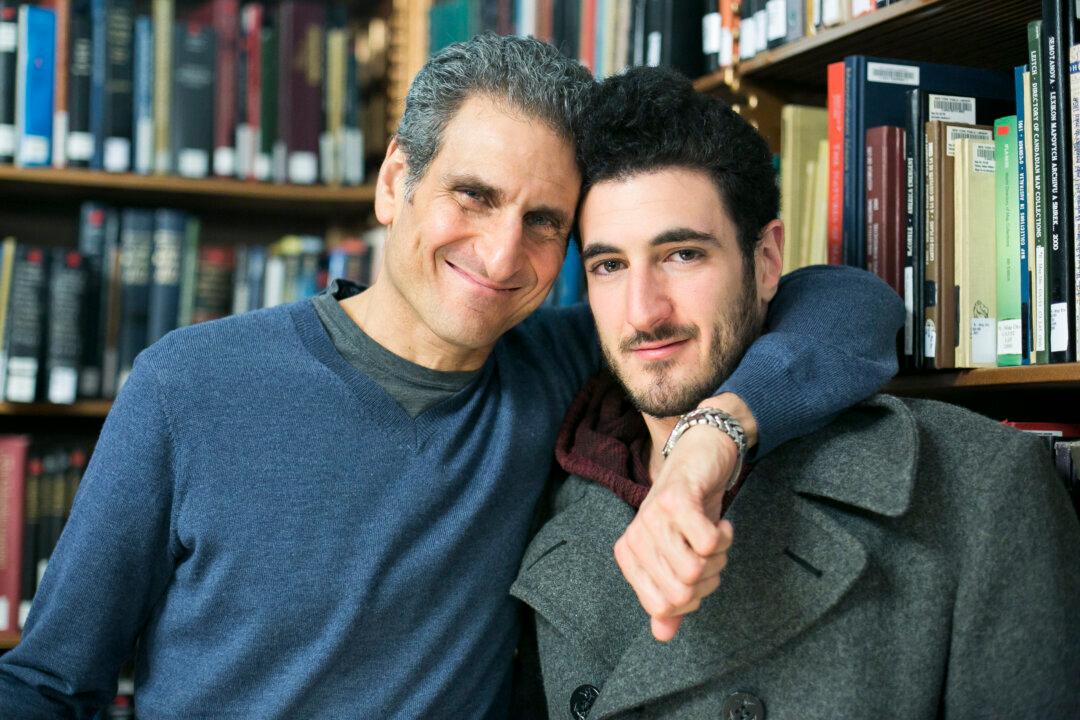

When Brooklyn native Joe Cohen visited his father’s workplace as a child, he felt like a VIP.

“He was the man. You walked in—I was like a prince because I was Alby’s son,” said Joe Cohen.

Albert Cohen was a foreman at a plastics factory, responsible for hundreds of workers, and the father of three boys. He was a man of honor. His word was his bond, according to his eldest. He was soft-hearted and generous. “Season tickets for the Giants, the Knicks, coach, umpire, he was involved. I was into sports.”

Albert Cohen was there for his son, physically. But he was the stoic child of immigrants from Aleppo, Syria, not a man of words. “Going to work was what he did.”

His son yearned for openness between them. It pained him that his father “did not know how to communicate.” He vowed to do this one thing differently for his own child.