Institutional investing is easy. Portfolio managers and chief investment officers of large insurance companies or pension funds often don’t have much choice.

After all, their investment behavior is determined by often strict mandates, which prohibit a large deviation of certain positions against the benchmark, or ban investing in certain assets altogether.

This is one of the reasons why so many of these institutions readily invest in government bonds, which have a negative yield, which means the institution has to pay for lending out money. As of February, around $7 trillion, or 30 percent, of all government bonds had a negative yield, according to Bloomberg calculations.

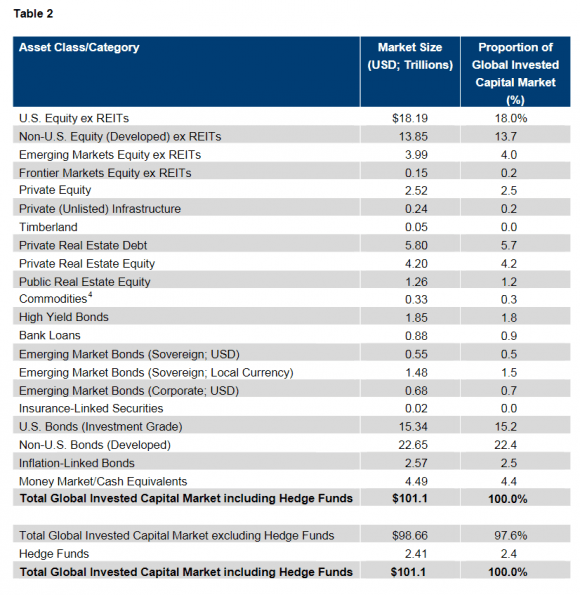

Total institutional assets and where they are invested. Hewitt ennisknupp