AUSTIN, Texas—Rick Perry spent four years after his 2012 presidential collapse trying to ensure that “Oops” wouldn’t be the final word on his political career.

It didn’t work.

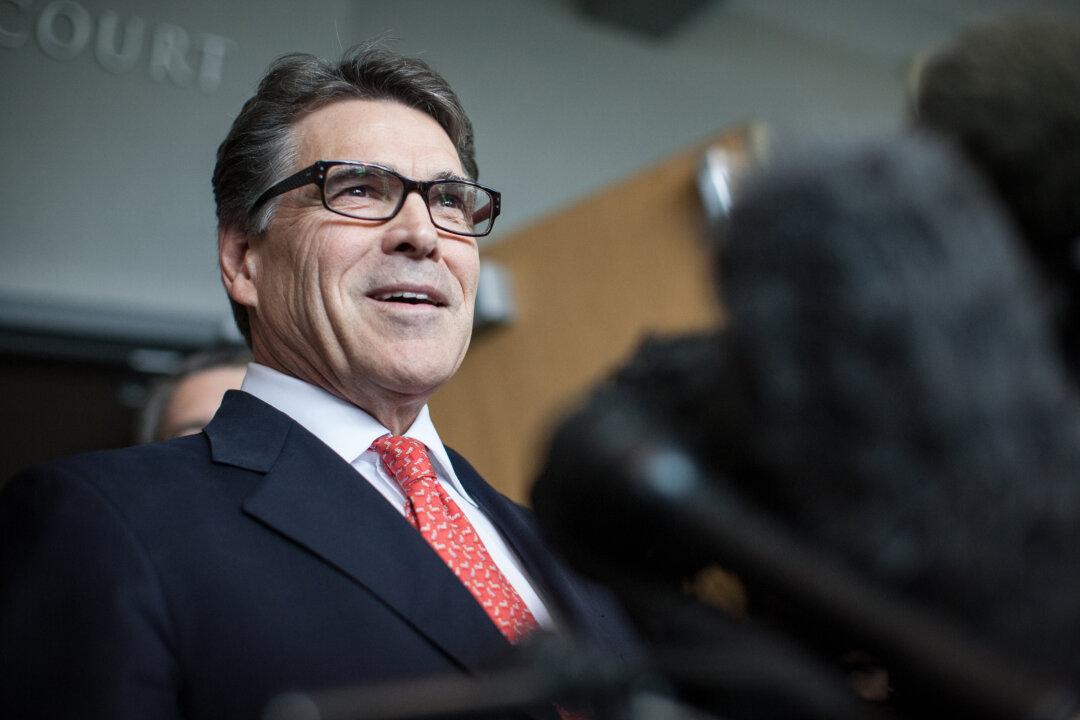

For the 2016 race, the longest-serving governor in Texas history swapped cowboy boots for eyeglasses, hit the road again, promoted his state’s job-creating prowess, boned up with policy experts. This would be a humbler, better prepared candidate, ready for the national spotlight, he promised.

Now, barely three months after Perry announced presidential bid No. 2 in a broiling airplane hangar outside Dallas, the reboot is history.

So, too, seemingly is the political career he wanted to revive.

“It’s a fool’s errand to think, ‘I ran before, I made these mistakes so I’ll fix them and everything will be fine,'” said Dave Carney, the architect of Perry’s 2012 campaign. “It just doesn’t work that way.”

It was no surprise when Perry announced Friday in St. Louis that he was suspending a campaign that was nearly broke and polling at close to zero. Still, such a precipitous drop was once hard to imagine for a savvy politician who had presided for 14 years over Texas and its booming economy.

Perry, 65, hasn’t announced his retirement, but so far there’s been no repeat of the pledge, made after the 2012 debacle, not to ride off into the political sunset.

He could turn up on the political speech circuit or find work as a TV analyst. But Perry appears to be out of options for elected office. A U.S. Senate run would mean challenging Ted Cruz, a tea party favorite elected in 2012 and now among the pack of GOP presidential hopefuls, or John Cornyn, the second-ranking Republican who just won a new term last year.

For now, expect Perry and his wife, Anita, to hang out at their recently built home in rural Round Top, about 80 miles from Austin and a stone’s throw from football games at the former governor’s beloved Texas A&M.