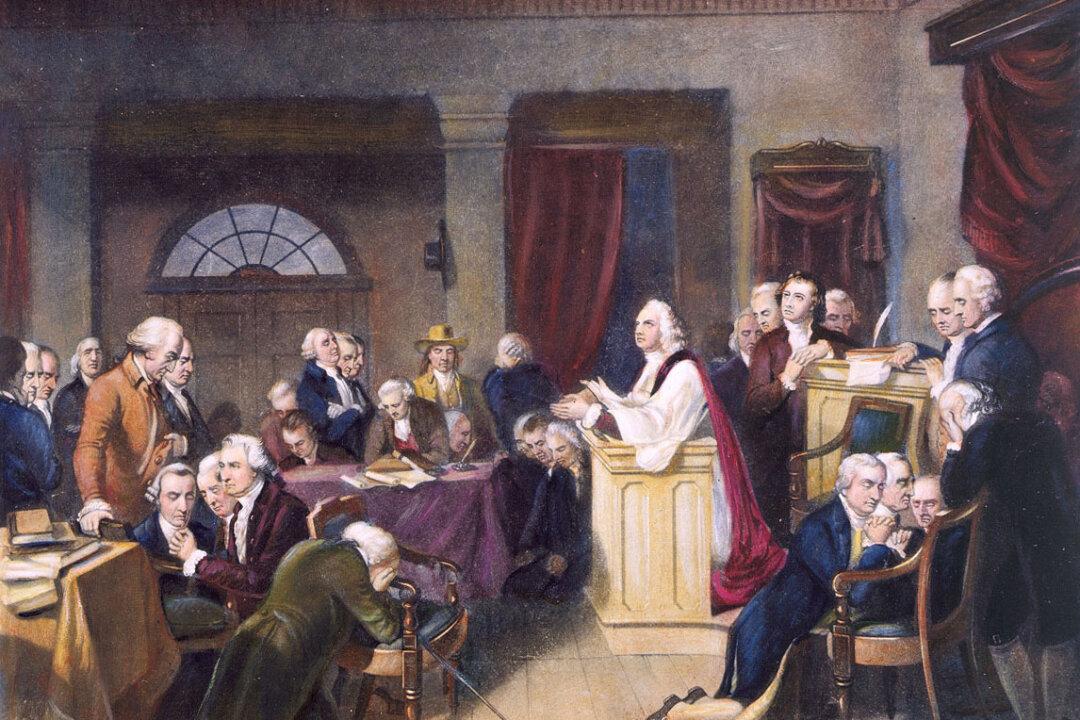

Our country is as divided today as at any time since the Civil War. Many people fault colleges and universities for today’s political acrimony and worry that those divisions are making a second Civil War inevitable.

West Virginia University research professor Jeffrey E. Paul asserts that universities are culpable for much of today’s societal schisms and explains why in his cogent book “Winning America’s Second Civil War: Progressivism’s Authoritarian Threat, Where It Came From and How to Defeat It.”