“Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee” is a compelling biblical painting by the legendary artist Rembrandt van Rijn. Created early in his career, this turbulent, powerful picture is the only painted seascape in his oeuvre. The work is considered one of the most important examples by the artist owned by an American institution; it is part of the collection of Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. However, the canvas is not viewable. It was stolen from the museum in 1990 along with 12 other artworks during a brazen heist, and it has yet to be recovered.

Patroness of the Arts

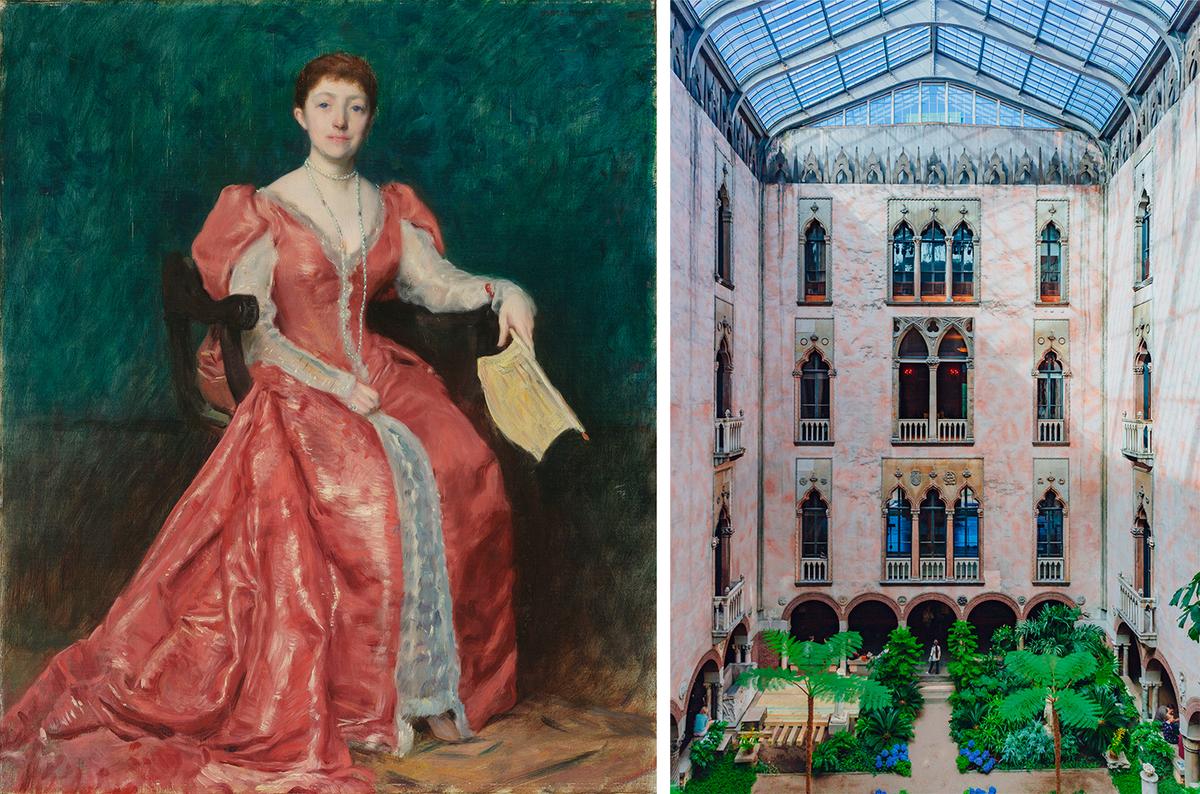

(L) A portrait of Isabella Stewart Gardner from 1889 by Dennis Miller Bunker at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. (Public Domain) A view of the inner courtyard and garden of Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Mark Zhu/Shutterstock