Jean-Jacques Rousseau cried out at the beginning of his landmark work “The Social Contract”: “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.” Rousseau’s work focused on one of the most essential concepts that sired the Western world from “medievalism” and protected people from being vulnerable to the whims of a despot or philosopher king alike, either of whom were really only responsible to their own sensibilities validated and legitimized by “divine right.”

The Western world moved from a world filled with edicts of the “sovereign” to a world ruled by “sovereign states.” Terms like the “general will” and “social contract” and “government of, by, and for the people” were disseminated everywhere throughout the newly “free” world.

These revolutionary ideas became concepts whose meanings and understanding were increasingly embedded in the educated classes, spreading rapidly to workers in the fields and laborers in factories and shipyards, all of whom were to participate in the benefits of a newly free and democratic society as the 18th century origins led to 19th century codification.

It started first narrowly, as with only land owners voting in the original U.S. Constitution, and then ever more broadly until by the time the 20th century had finished dealing with two world wars, the Great Depression, and countless other horrors, we saw an evolution from an agricultural society to the industrialized and then technologically advanced society of today.

So it is these core beliefs and the breakthroughs of the Enlightenment, its ideas and concepts, that are so crucial to understanding the context in which the artists of the 19th century lived. They were, in fact, addressing the very heart of Enlightenment thought.

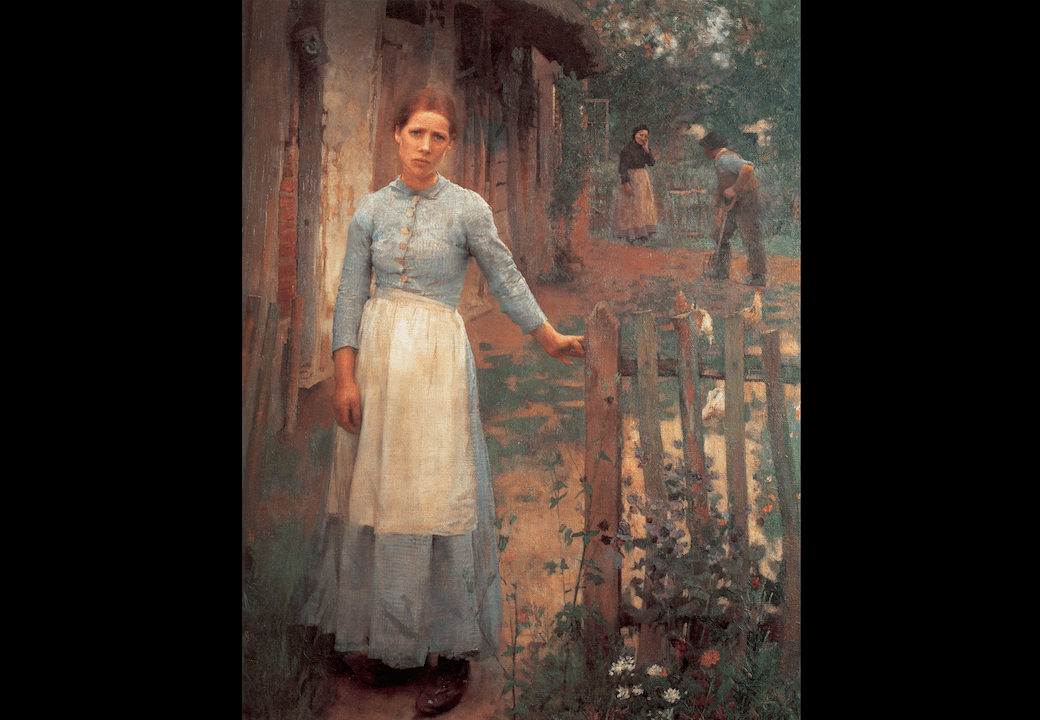

Bouguereau painted young peasant girls with a solemn dignity and a hushed and reverential beauty. One of his works shows a strong but beautiful peasant girl holding a staff and looking the viewer directly and unabashedly in the eye. She is standing her ground, so to speak.

In another major work, a life-size Gypsy mother holds her daughter, and both are standing on a mountaintop, looking down at the viewer. Their gaze, too, is direct but welcoming. In this painting, Bouguereau is elevating these Gypsies by silhouetting them against a vast sky with a low horizon line. We are looking up to them.

Their kind and welcoming expressions imply their acceptance of us; the viewer is asked to return this show of respect, which can only be properly echoed by our acceptance of them regardless of the lowly status of their birth. The very truth and reality of their birth, once a negative, now elevates them to the heavens.

Now, in the 19th century, all people doing any and all activities were considered worthy subjects and themes for the artists to address. Subjects included paintings of the poor and homeless, women thrown out in the cold, or children toiling until late at night enduring 16-hour work days.

There were scenes of marriage and children and family life, scenes of schools and courts and hospitals and industry, parks and mountains, and countless other topics.

For example, a new popular theme was of hypocritical clergy preaching to give up worldly possessions from their opulent apartments filled with art and antiques and personal servants. How revolutionary this was for artists.

When Vibert, Brunery, or Croegaert satirized the clergy and painted cardinals in sumptuous surroundings, playing cards with pretty young socialites, or hiring the services of a fortune teller, they were saying that the clergy was human and vulnerable to the same weaknesses and frailty of character as other people. But beyond that, to spoof the clergy represented our newfound freedom of speech.

A modernist professor once said to me, “How inane and silly to show cardinals in silly poses like that.” His prejudice blinded him from even beginning to figure out what Vibert had done—what rules of conduct he had broken from the prior rulers of society.

We have been taught to elevate artists for breaking rules and conventions of perspective or for undermining realistic drawing, or daring not to follow prior precepts, but the academic artists who had been on the front lines helping all of us to win our freedoms and rights were also helping to create a climate where it was even possible to consider breaking the rules of art. In previous centuries, an artist would have had his head cut off for spoofing cardinals in this way.

From exposing societal ills and portraying the value and equality of all people, it was but a half step away to explore the personal inner life of individuals and to value and elevate mankind’s hopes, fantasies, and dreams. For academic artists and writers of the 19th century, humanity was what counted, and everything that makes us human—how we see ourselves and how we see the world. Humanity was glorified, and people of every type and shape, every nationality and color, and every occupation and avocation.

This is Part 9 of an 11-part series presenting the speech given by Frederick Ross at the February 7, 2014, Artists Keynote Address to the Connecticut Society of Portrait Artists. Frederick Ross is chairman and founder of the Art Renewal Center (www.artrenewal.org).

|Updated: