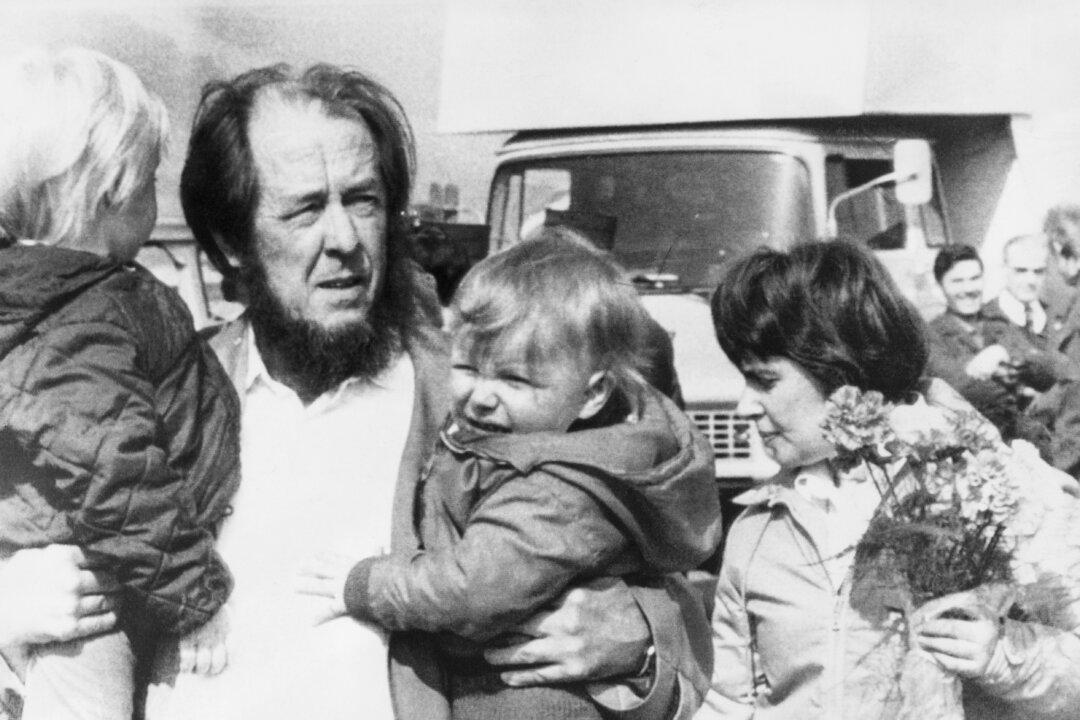

“How easy for me to live with You, O Lord! How easy for me to believe in You!” The believer Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn had every reason not to believe: poverty in childhood, the front lines in Hitler’s war, arrest, torture, imprisonment, hard labor, cancer, persecution, and humiliation. All these were the birth pains of his faith and the catalyst of his great literary works.

He was born on Dec. 11, 1918, in Northwest Russia, and was raised in the Russian Orthodox religion, a crime in the Soviet state. Government schooling and a science degree fashioned him into an atheist for a time, but only a time.