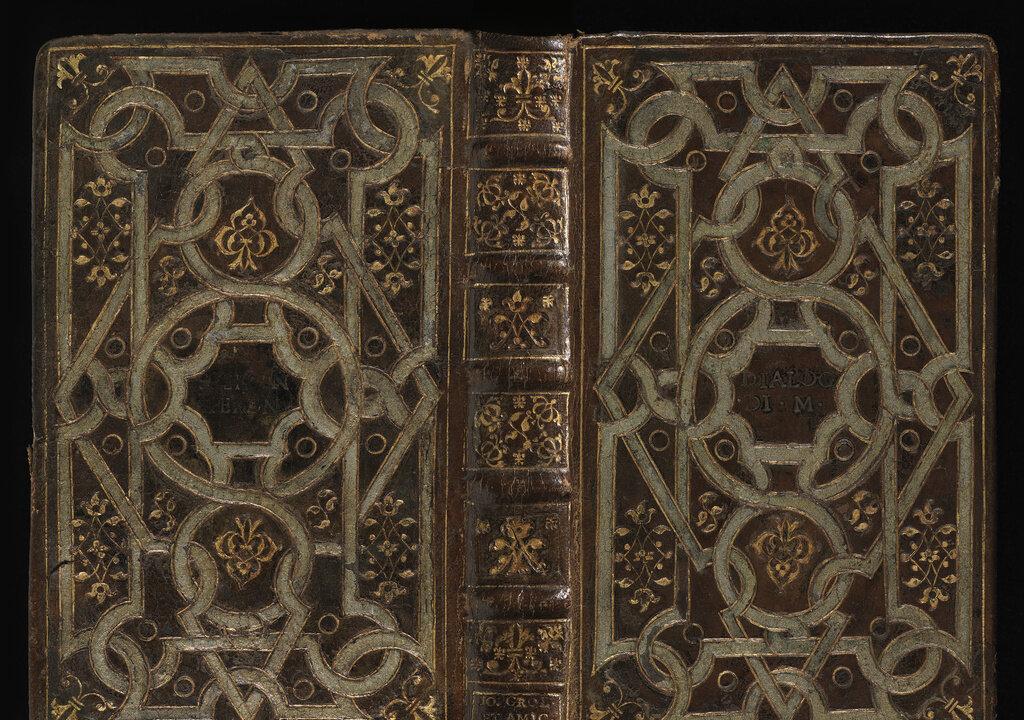

Like the paintings and sculptures of the Renaissance, the era’s books and their artisanal bindings uplifted man to moral ideals. During the 16th-century Renaissance in France, one young statesman in particular, Claude III de Laubespine, adored commissioning and collecting ornately designed books.

“Imagine seeing this magnificent array of front covers when you walk into the library room,” said John Bidwell, a curator at The Morgan Library & Museum, in a phone interview. “They’re tokens of knowledge and learning.”