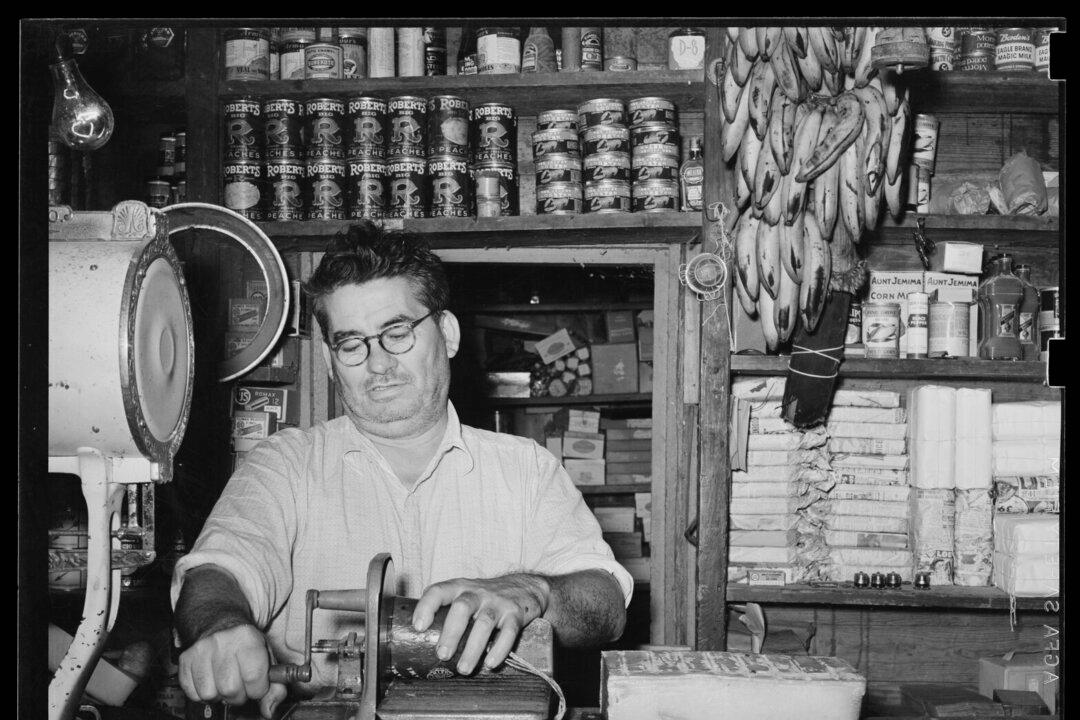

“Shop local.” For a good part of America’s history, that bumper sticker with its implicit frown at internet shopping would have been meaningless. For a man on foot or a woman in a buggy, local generally meant sticking close to home.

Because of these restrictions of time and circumstance, small towns across America were once largely independent entities. They sported their own gristmills for grinding corn, wheat, and other grains. A village blacksmith hammered out everything from horseshoes to door latches to nails. Schools and churches were just up the road, while a trip to and from the county courthouse or a larger town might eat up an entire day. All these small enterprises and institutions did double duty as community gathering places where neighbors exchanged news, dickered over business and trade, or simply visited.