EDINBURG, Texas—“It’s not just a horse, it’s a mustang.”

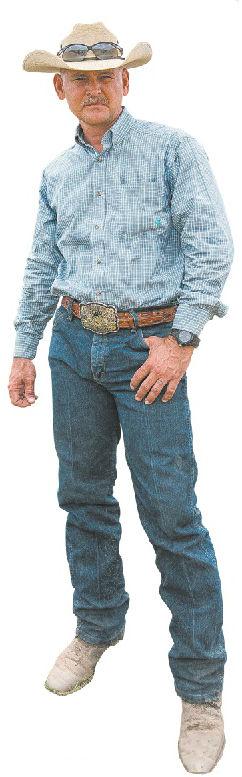

Ruben Garcia, horse patrol coordinator for the Rio Grande Valley Border Patrol Sector, is unbridled in his praise of the horses employed on the Texas border.

It’s fast and volatile work, and the mustangs Border Patrol adopts are perfect for the job.

The horses are wild for the first two to three years of their lives.

“Completely roaming free in the ranges of the north, northwest, the horses had to fend for themselves,” Garcia said. “They have an instinct, a level of survival unparalleled. You’re not going to get that from a domestic-bred horse.”

The wild horses are corralled by the Bureau of Land Management and sent to the Hutchinson Correctional Facility in Kansas, where the prisoners break them in with a week or two of training and a handful of saddle rides.

When Garcia heads up to the prison to select horses for adoption, he’s searching for the right personality.

“We’re looking for horses that have the heart, the willingness, so I know I can train that horse and that horse is going to take care of my riders,” Garcia said.

“When we train them, we don’t want to break that American spirit. It truly is a heritage, truly an American heritage. And they’re wonderful animals. I want to work with that spirit.”

Once adopted, the mustangs are brought to the Rio Grande Valley for two to three months of specialized training at the Border Patrol facility in Edinburg, Texas.

“We [train] not just to ride, but to ride down in the Rio Grande, some of the most adverse terrain in the country, some of the most unforgiving,” Garcia said.

“Everything has thorns ... everything stings, everything bites. And we operate at night, usually with a helicopter hovering overhead. That’s what these mustangs have to be trained to do, and they do it brilliantly.”

“So we’re looking with our night vision, we’re calling the folks that manage the technology—nobody is seeing anything.

“Five, seven minutes later, sure enough, through the thickest brush, we get traffic, we get a group of aliens.”

The horses are invaluable in the many dense areas that are impassable to trucks and even ATVs. The agents on horseback can quickly track illegal aliens that are running or hiding.

The horses are used in areas where criminals and drug runners operate, rather than where families and young people seeking asylum cross. Asylum-seekers want to be picked up by Border Patrol, whereas criminals and drug runners will do everything they can to evade capture.

Border Patrol chief Carla Provost said the agency has come a long way from the days when binoculars and a horse were the latest technology.

“Yet, even today, those remain some of the most reliable tools,” she said in a video to Border Patrol agents.

Garcia recounted an experience that corroborated Provost’s sentiment.

“It was about 2 o'clock in the morning. Pitch dark. Quiet. We have a lot of technology, we have a lot of infrastructure, we have sensors and cameras,” he said.

“The horse started breathing hard, and I could literally feel the horse’s heart thumping with my right leg. His ears were tuning in. It’s that wild mustang survival instinct. They know there’s something coming. They know there’s a threat.

The runners will often try to spook the horse into throwing its rider, which could buy them enough time to retreat back to Mexico.

It happened to Garcia 15 years ago, which is why he retains the strict policy of patrolling in teams of two.

“We were actually ambushed once down by the river,” he said. “One of my partners was thrown down from the horse.”

The individuals started throwing rocks at the agents, who “had to escalate in the use of force,” as Garcia puts it.

“In the end, we were able to secure the horse, the rider, and get back to safety,” he said. “But the reality of the job is that it’s very dangerous.”

Garcia has coordinated the horse program in the valley for four years and has a formulated training regimen based on a national curriculum.

He trains the horses to strict criteria—and then it’s time to train the humans. He just selected a fresh crop of agents to train for a three-year stint in the saddle.

“In 30 days, we need to get them ready to go out into the field to do law enforcement work—on a horse that was once a wild mustang,” he said.

Eight riders were selected out of a pool of about 40 qualified applicants. Trainees must have been a Border Patrol agent for at least three years before they can apply, but they don’t need riding experience.

“We get people here with dressage background, we have ropers, we have barrel racers. And I tell everybody, there’s only one way—the Border Patrol way,” Garcia said. “So we look for folks with the ability to follow instruction.”

One of the most challenging parts of the process is to pair the right horse with the right rider.

“It’s kind of like Match.com,” he said, “because if I give the wrong horse to the wrong person, they’re going to go get hurt.”

Marlene Castro, supervisory Border Patrol agent, said that as with the K-9 program, the animal and human have to have similar personalities.

“You can’t have high-speed with someone who isn’t so high-speed. The animal has to be as active as the agent,” she said.

“She’s absolutely right,” Garcia said. “I’m a little on the high-wired, ADD side, so I need horses that are hot horses, active horses. Gimme a slug, a big old draught, that looks beautiful but barely moves ... you know what, it drives me nuts.”

Garcia’s horse, an adopted gray from Kansas called Muñeco, is one of approximately 40 in the herd made up of mustangs, except for three that were seized from drug runners. Muñeco’s name translates to “doll” in English.

“A doll can be Ken, or it can be Chucky,” Garcia said. “If you piss him off, you’re going to get Chucky.”

“So let’s just say that I tend to be real nice to that horse,” he said with a laugh. “We’ve come a long ways. We’ve actually both grown and learned together. I’ve become a better rider, a better trainer.”

New Recruit

Edgar Alvarez was one of the lucky ones to be chosen for horse patrol training. A Border Patrol agent for nine years, Alvarez now has an 800-pound challenge on his hands.He was paired up with Hidalgo four days ago and despite coming off once (due to “operator error,” he says), he’s feeling confident.

The first three days were all bareback riding, and yesterday was the first time the trainees used a saddle.

“My body’s aching all over. You use pretty much all the muscles that you never used before, back, shoulders, arms, legs, thighs, everything, hips, everything. It really hurts,” he said. “But it’s a good feeling. You feel accomplished ... I feel I could get on any horse right now.”

Alvarez is already looking forward to getting out of the arena and onto the front line, where he will do 10-hour shifts averaging seven to eight hours in the saddle, mostly at night. “It’s going to be awesome,” he said.

The trainees have classroom work, too. They must get at least 80 percent on a written exam that includes anatomy and physiology, saddles and equipment, and a lot of rules and regulations. They learn to ride correctly and to look after a horse properly.

Twice a year, they also have to be cleared on shooting their handgun from horseback.

During the training, instructors like supervisory agent Jeff Wiggins are constantly testing the riders, pushing them to the next level.

“Anytime you’re riding a horse, you’re training that horse. But you’re either training it to do the right thing, or you’re training it to do the wrong thing,” Wiggins said.

As the trainees ride, the instructors are “yelling and hollering” at them and asking them all kinds of weird questions.

“We want them, their mind, to be able to answer questions, let them think about different things, and let the horse-riding be a natural thing to them,” Wiggins said.

It’s impressive how far the trainees have come after only a week—some have never ridden a horse before.

After four weeks in the arena, the trainees will spend two weeks training in the field before launching out on their three-year assignment.

Garcia said a lot of agents don’t want to finish horse patrol once the three years are up.

“Because the truth of the matter is, the people that are here, they do it because it’s in their heart. It becomes part of you, it’s in your blood, it’s a lifestyle,” he said. “And right now these agents could be in a Border Patrol unit, in the air conditioning. Never mind that it’s 110 degrees, 80 percent humidity—they choose to be here.”

Friends Read Free