SCOTTSDALE, Ariz.—Maya Morsi and her boyfriend, Eddy, had been waiting in the holding area for hours. They were confused, hungry, and eager to be on their way to their vacation spot in the city of Rocky Point on the Gulf of California in Mexico.

Morsi could see the sun setting through the window in the prosecutor’s office, not far from Arizona’s southern border. She glanced anxiously at her expensive Cartier watch, then at the metal shackles around her ankle.

She wondered, where is the prosecutor? He should have been here by now.

In an adjacent room, Eddy sat quietly in a small jail cell with no running water.

It was supposed to be a romantic getaway for the young couple from Scottsdale, Arizona—not a one-way trip through Mexico’s convoluted legal system.

The military police officers who arrested them said they were to first meet with the local prosecutor to face charges. Maybe they'd pay a fine, and be back on the road in a few hours.

None of that happened, Morsi said.

The couple’s nightmare began the moment they saw the flashing red light on the Mexican side of the international border near Lukeville, Arizona, which signaled them to pull over to undergo a random vehicle inspection.

Fortunately, Eddy spoke Spanish.

Countless Americans Caught Out

Morsi said the 9mm Glock was the registered firearm she'd kept for the past nine years for its sentimental value.The couple told The Epoch Times they did not know about Mexico’s strict gun laws. But in the eyes of the Mexican authorities, ignorance of the law was no excuse.

Each year, countless United States citizens end up in a similar dilemma facing long prison terms and stiff fines for possessing an illegal firearm in Mexico. And while getting arrested with a firearm at the border is easy, getting out of trouble and back home is not.

Often, the process can take months and cost thousands of dollars wading through Mexico’s complex bureaucratic court system.

According to the U.S. State Department, American citizens are subject to local laws in Mexico, which often involve severe consequences once broken.

“If someone violates local law, even unknowingly, they may be expelled, arrested, or imprisoned,” according to a State Department spokesman speaking on background.

Accidental Border Crossing

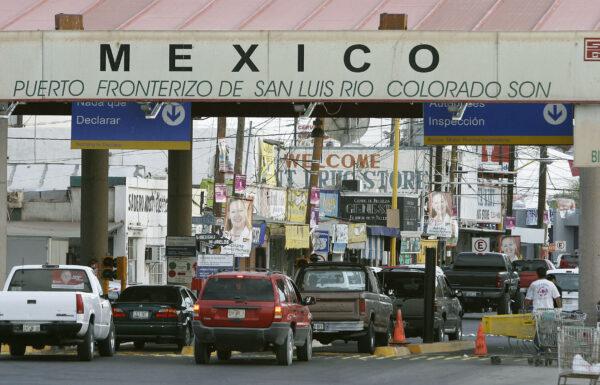

In Arizona, where it is legal to carry an open or concealed firearm without a permit, there are nearly 180,000 registered gun owners. An accidental border crossing with a firearm is not as difficult as it sounds.An Arizona resident explained how easy it was for him to get caught up in the travel lane at the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol’s (CBP) port of entry in San Luis, Arizona, by accident.

Once he was in line, there was no way to get out.

It was late at night in January. The resident said he was traveling along the US95 southbound when he noticed white traffic cones converging into a single travel lane leading to the port of entry.

“I had no intention of going to the port of entry or Mexico. No signs were directing me where to turn or pull off to the side if I went too far or changed my mind,” the resident said.

The resident said his only course of action was to continue with the traffic flow and hope the Mexican border agents would understand his predicament.

He showed one border agent his Arizona driver’s license and two other forms of ID.

The heavily armed and masked agent spoke no English. He then briefly conversed in Spanish with his superior and waved the driver into San Luis, Mexico.

Underneath a pile of papers on the front passenger seat of the resident’s car was a loaded .22-caliber Beretta handgun the agents had failed to notice.

For the next 20 minutes, the resident nervously drove around the dark streets of San Luis, searching for the port of entry back into the United States.

But all the signs were in Spanish.

“Finally, I saw a sign in English welcoming me to the United States,” he said.

At the checkpoint, he explained how he had ended up in Mexico to a CBP agent. When asked if there were any firearms in the vehicle, he said, “yes.”

The resident was placed in handcuffs, led by several border agents into a holding facility, and asked many questions.

An agent told the resident he was not under arrest or facing charges in the United States but that he was fortunate the Mexican authorities did not search his vehicle.

“Did you tell them about the firearm?”

“No,” the resident said.

“Good.”

In hindsight, knowing the strict laws against firearms in Mexico, “I'd probably be sitting in a Mexican prison right now,” the resident told The Epoch Times.

Tania Pavlak, the public affairs specialist for the Yuma County Sheriff’s Office, said getting stuck in the line of border traffic from San Luis, Arizona, into Mexico happens often.

It happened to her about two years ago.

“I was trying to find a business,” Pavlak said. “As I was driving around and searching for the address, I took the street that takes you down to the border. The next thing I knew, I was behind cars, and there were cars behind me. I’m like, ‘What? Wait.’”

“Clear signage could prevent that. And also a last-minute ‘out’ area. Because it was like block after block [of cones], I expected a barricade not to be there or an area to turn into—nope.”

Pavlak finally decided to step out of her car, move a traffic cone out of the way, maneuver her vehicle to the far left side into a business parking lot, and replace the cone.

“I decided I was not going to go [to Mexico],” Pavlak told The Epoch Times.

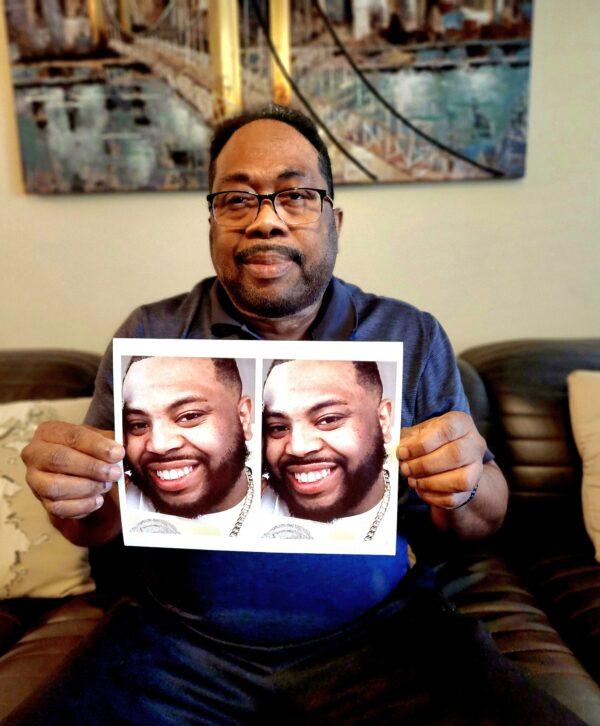

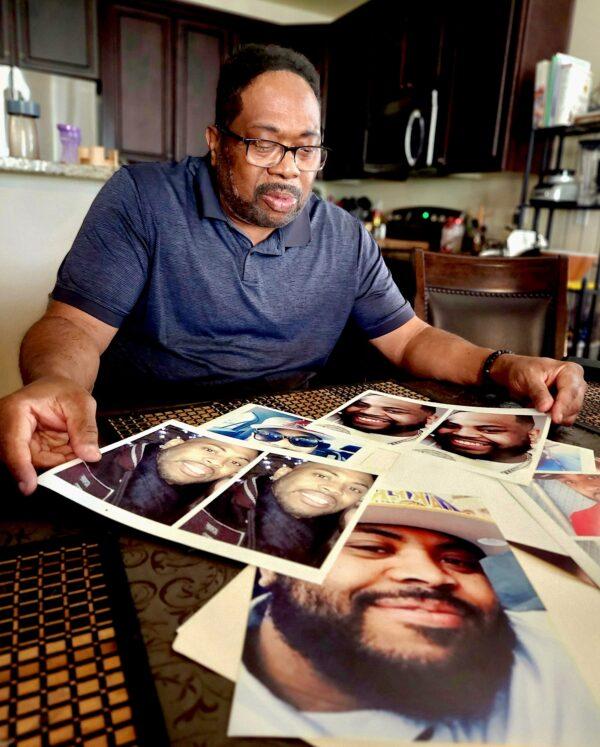

Antonio Harrison of Gilbert, Arizona, said that his son Drew was traveling with his fiancee when their vehicle was stopped for a random inspection at the Arizona southern border, in Lukeville, in May 2022.

Drew realized too late that he had unwittingly brought an AK-47, a handgun for target shooting, and ammunition inside the vehicle.

Antonio said Drew is now facing up to 15 years in prison if convicted on weapons charges while he awaits the disposition of his case in a maximum security federal prison in Hermosillo, Mexico.

His fiancee will not face charges.

“Even when he got to the border, it didn’t click that he had guns,” Antonio said. “We expected to see both of them coming out together.”

Drew, 33, has been stuck in prison since Mother’s Day.

“It took me almost two months before my paperwork was approved to go and see him,” Antonio said. “He’s broken down. It’s like, ‘Dad, I thought I’d be out of here by now. What’s going on?'”

Karen, of Tucson, said Mexican authorities on Christmas Eve stopped and randomly searched her vehicle at a border crossing in Douglas, Arizona.

Inside the Hummer, police found a small cache of .22-caliber rifles under the seat.

In Hiding Since Fleeing

The rifles belonged to Karen’s friend, who loaned Karen the use of the Hummer to cross the border to buy cigarettes in Mexico for less money.“I was in a hurry,” Karen said. “I jumped in the Hummer and hit it to the Border Patrol station. The red light went off, and they sent me to a secondary” holding facility in Mexico.

Karen said she was looking at two to three years in prison for illegal weapons charges. She eventually fled Mexico when she had the chance after her boyfriend posted her bond.

She has been in hiding ever since.

It’s a common but false mindset among Americans, Karen said. Before her arrest, she assumed traveling through Mexico was as simple as traveling across the United States and that both countries were alike in most respects.

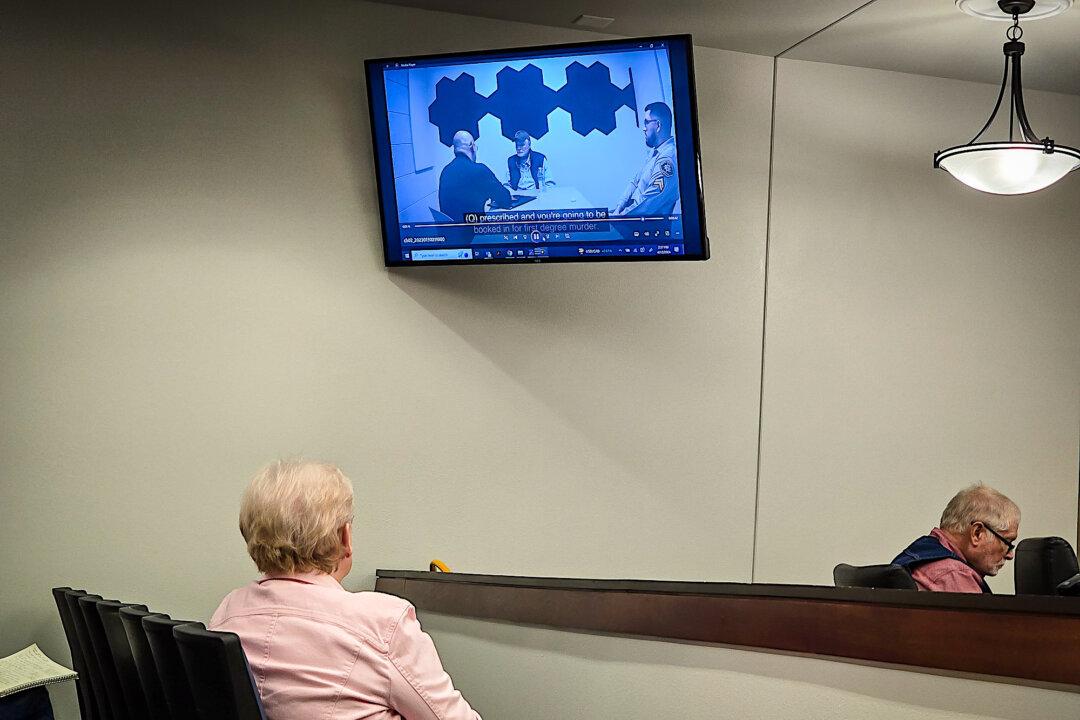

She quickly discovered that there were stark differences between the United States with its “common law” and Mexico’s “Napoleonic law,” where the accused is guilty until proven innocent.

And in many cases, it takes less time and costs less money for an American who pleads guilty and accepts whatever sentence the judge decides to impose, Karen said.

Lengthy Prison Term

He said Drew is looking at a lengthy prison term for a crime he feels does not fit the statutory punishment.“He just had a newborn when this happened. He needed to get away on vacation. I said, ‘Cool, man. Go and enjoy yourself,” Antonio said.

On Mother’s Day, Drew’s father-in-law, a former U.S. Customs and Border Patrol agent, called Antonio on the phone to deliver the news that Drew was in jail.

“You guys better get down here right away, to Hermosillo. Drew’s in trouble,” Antonio recalled him saying, and thought, “Where in the hell is Hermosillo?”

Nearly a year later, Drew remains in legal limbo awaiting sentence.

“That’s what all these appeals are about,” Antonio said.

‘When They Smell Money’

“There are prosecutors—when they smell money, they’re not letting you go,” Harrison told The Epoch Times as he spread pictures of Drew on a dining room table.“Listen, they don’t care if you’re innocent. They consider you guilty because you broke their law—and they know you have money. It’s like, ‘It’s time to pay.’”

According to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, an estimated 200 to 300 United States hunters are arrested and fined each year after they fail to declare firearms and other weapons at the border with Canada. However, many arrests do not get reported.

The State Department said the agency does not keep track of the number of U.S. citizens arrested and charged with weapons violations in Mexico.

However, one of the agency’s “highest priorities” is to help U.S. citizens arrested outside the United States.

“Weapons laws in Mexico vary by state, but it is illegal for travelers to carry weapons of any kind—including firearms and ammunition [even used shells]—without a permit from the Mexican government,” a State Department spokesman said.

“Illegal firearms trafficking from the United States to Mexico is a significant concern, and the Department of State warns all U.S. citizens against taking any firearm or ammunition into Mexico.

Ira Beavers of Glendale, Arizona, was sentenced to nearly three years in prison after he allegedly forgot about the 9mm Glock in his car while crossing the Arizona border into Mexico on July 30, 2021.

His wife, Francine Nicholson, was also in the vehicle but was not charged with a crime.

“Imagine going on vacation only not to make it to your destination and not to come home,” said Nicholson’s best friend, Deydra Stevenson, who set up a GoFundMe page and raised $15,480 to help pay Ira’s legal expenses.

Stevenson said the family paid $7,500 to an attorney appointed by the U.S. Consulate but expected a different result. Ira spent two years, nine months, and 17 days in prison as a result of the “incompetence and dishonesty” of the legal system in Mexico, Stevenson said.

“The court didn’t even allow Ira to bond out.”

Ira’s mother passed away while he was behind bars.

‘In Prison For Same Thing’

Stevenson said she has received more than 100 emails from people in the United States who know someone imprisoned in Mexico on a firearms charge.“‘Call me, please! My brother is in prison for the same thing.’ It happens to me all the time,” Stevenson said.

“I have so many people who have reached out to me. I try to help these people as much as I can.”

Stevenson said that money and close ties to people with access to resources help move the court process along whereas prisoners who don’t have these things are out of luck.

“That’s the key. If you have money, you’re good. If you don’t speak the language, you stay there for a long time. You have to know somebody. It’s who you know.”

Beavers and Drew Harrison are both African-American. Stevenson suspects they were arrested because of racial profiling.

“I think race had a lot to do with it,” Stevenson said.

US Gun Permits Not Valid

Busch was found guilty and sentenced to more than three years in prison and given a fine of $1,087.It’s unknown how the system will impose Busch’s sentence to prison.

The State Department said that anyone caught entering Mexico with a firearm or ammunition could face severe penalties including prison time. In that event, the person in custody should ask the Mexican authorities to notify the nearest U.S. embassy or consulate “or do so themselves if possible.”

The department’s role includes prison visits, providing information on how to find an attorney, contacting the detainee’s family and friends, and ensuring the incarcerated person receives humane treatment.

However, the agency cannot represent U.S. citizens in court, pay legal fees, or obtain a U.S. citizen’s release. American gun permits are not valid in Mexico, the State Department added.

$25,000 to Secure Release

Eddy said it cost $25,000 to secure his release on Feb. 2. He has about two years of probation—a benefit given to first-time offenders—left to serve and two more court appearances in Mexico later this year.“It’s good to be home again,” Eddy said.

The authorities in Mexico still have all his personal belongings, including his pickup truck, iPhone, and MacBook Pro.

Karen said she was in a “state of shock” during her eight days spent in the women’s prison in Hermosillo before her provisional release by a judge.

“Honestly, I didn’t know the gun laws were that way. I just went for a carton of cigarettes and wanted to come back,” she said.

Once her boyfriend posted bail, “I fled the country,” Karen said. “I don’t even know what the repercussions will be like.”

Karen said she walked across the border into the United States with only her clothes and a copy of her driver’s license.

“How much money do you have on you?” a National Guard member had asked Eddy, who had $200 in his wallet, Morsi recalled.

“Oh, that should cover the mandatory medical inspection,” the police officer said.

Eddy handed over the money. He found out later the service was free.

Morsi, like her boyfriend, had to forfeit her personal belongings—an iPhone, a Cartier watch worth $10,000, a gold ankle bracelet, a Louis Vuitton purse with a $1,000 cash value, her $800 handgun—and priceless peace of mind.

“I don’t even know where everything is at this point. Not in my wildest dreams [did] I think I'd go through such trauma,” Morsi said.

To make matters worse, when Morsi checked her email, an 18-page order from the Mexican court system had reopened her case.

The notice claimed the judge had made a mistake setting her free without charges. She would have to stand before a judge to face new charges of being inside Eddy’s vehicle when the couple got arrested.

Extradition Treaty

Karen said the judge threatened her with an arrest warrant if she left the country, calling her a flight risk and saying her “reach” included the United States.In 1978, the United States and Mexico signed an extradition treaty for serious felony charges such as murder and drug trafficking.

“If you don’t have money, you can’t do anything,” Morsi said. “To this day, they’re trying to revoke my freedom. They’re trying us in separate cases. Mine is a whole new case. It’s like a sub-case. The charges are the same.”

“I don’t trust Mexico. I don’t trust the lawyers helping us. Who should I trust? A prosecutor can keep investigating for as long as they want before you get sentenced on whatever charge.”

Morsi said she is hopeful the Mexican court system has “bigger fish to fry” than her case.

“Do you want to [deport] an American to Mexico for a gun they kept? They treat us like murderers. Like we’re El Chapo. It’s a simple gun.”

Morsi said the time she and Eddy spent in jail has left her “full of hate and anger.”

Know the Laws of Foreign Countries

“You can see it in real life. The corruption is so bad. The judge is corrupt. The prosecutor. The lawyer. Everyone. You have no choice but to go with the flow. Whatever they want, that’s what you do,” Morsi said.“Something needs to be done. If you think of the big picture, I thank God for Eddy and his family. If I had been here alone, I would have lost my job. I would have lost my home; I would have lost my car. I would have had no one to help me.”

U.S. Customs and Border Patrol spokesman Aaron Bowker said it is the responsibility of U.S. citizens to know the laws of the foreign country they plan to visit and make sure they are not carrying illegal firearms.

“Once you get to a certain point” at the border, “we consider it a meaningful departure,” Bowker said. “There’s a lot of security at that point.”

“If cars constantly made U-turns, keeping traffic flowing in one direction would be hard. When you’re close to the point of entry, it can also become a security concern. Cars are funneling out—that’s it. You funnel out.”

Bowker said travelers should be “completely honest and truthful” with border patrol officers and declare firearms or ammunition before they enter a foreign country.

“Then, you hope the situation works out for you. It’s the best you can do,” Bowker told The Epoch Times.

Morsi, a web developer, said her employer arranged her flight home to Phoenix.

It was an experience she will never forget.

“Once the flight attendant said, ‘Welcome to Phoenix, I started crying,” Morsi said.

“I was bawling. You have freedom here. I don’t take it for granted, but you forget about our freedom [in America]. It’s not like that in Mexico.”

Antonio Harrison said Drew encountered other Americans languishing in prison for weapons possession, including a police officer, a nurse, an old high school buddy, several teachers, a doctor, and a truck driver—in the months he’s been in prison.

“Drew told me there’s a guy in there for one bullet, and they’re talking about two years. It’s a racket—big time,” said Antonio, a musician, who gave Drew a Bible to lift his spirits.

Antonio also published five songs on YouTube about his son’s ordeal in Mexico. He even wrote letters to President Joe Biden, Vice President Kamala Harris, Arizona Sen. Mark Kelly, and Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs, pleading for help.

“I didn’t know what else to do,” Antonio said. “I’m calling presidents and governments. No response—nothing. Silence. It doesn’t sound like anybody’s listening. We’re over here by ourselves.”

“You know what I got? I got all this stuff about raising money. Can you donate to this? Can you donate that? Can you vote for that person? Gosh. They want all this from me, but I’m asking them to help get my son out of the country.”

“My eyes are wide open. The only help you get is from yourself and the people you know. We’re just hoping to get him home soon. I can feel he’s cracking,” Antonio said.

Antonio said he is willing to spend as much money as it takes—however long it takes—to buy Drew’s release from prison.

“Take his guns; give him a big fine. But don’t take his life.”

Friends Read Free