During the pandemic, it was hard to get a fix on Sino-American trade, but now that the oppressions of lockdowns and quarantines are lifting—in the United States as well as in China—some statistical clarity has returned. Two trends stand out. One, American producers clearly have begun to shift sourcing away from China; and two, China has markedly increased its purchases in the United States.

Some of this relative movement reflects Beijing’s policy during the pandemic, but it also has a more fundamental component based in relative costs. Some reflects Beijing’s efforts to comply with the trade deal hammered out between it and Washington in 2019 and sealed just before the onset of the pandemic.

Supply chain shifts show clearly in the data on U.S. imports. The robust response of the American economy to the lifting of pandemic-related strictures has sucked imports into the country from everywhere, as is usually the case when this country grows rapidly. According to the Commerce Department, U.S. imports of goods from all sources rose 33.7 percent in just the nine months between last June and this past March, the most recent month for which complete data are available.

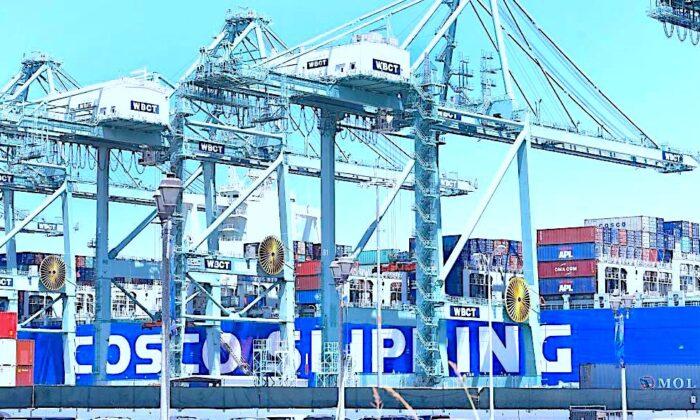

But goods imports from China are up only 6.9 percent during this time. Clearly, American business is sourcing elsewhere. Part of this, of course, is a question of security—not so much national security as supply-line security. During the pandemic, China held back on several vital products. Though Beijing’s action in the emergency is understandable, equally understandable is how it prompted American buyers to diversify their sources, and they clearly have begun to do that.

The turn away from Chinese imports has a longer-term component as well. For some time, labor costs in China have been rising faster than elsewhere. According to China’s Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, the average wage in China increased between 2012 and 2019 at a striking 10 percent annual rate. This is only natural in an economy developing as fast as China’s, but it is a startling figure, and it has erased any cost advantage China might have enjoyed over less developed economies such as Vietnam, Indonesia, and several in Latin America.

During the pandemic, this rapid wage growth stalled, but now in recovery, there is every reason to expect it to resume. It had already convinced American buyers to look elsewhere for the kinds of bargains Chinese production once offered, especially in lower-tech products, such as toys, textiles, and shoes, once the almost exclusive purview of Chinese sources. This effect is evident in the data from before the pandemic or even before the 2019 “trade war” with the Trump White House. Between 2015 and 2018, all U.S. goods imports increased at an expansive 15.7 percent annual rate, but those from China grew only 3.1 percent a year.

The export side of America’s ledger captures the impact of the 2019 trade deal. According to the text of that agreement, China effectively made four promises. One was to stop Beijing’s practice of manipulating the foreign exchange value of the yuan to support exports. Two was to cease the widespread tendency of Chinese firms infringing on U.S. patents and copyrights. Three was to ease Beijing’s long-standing insistence that American firms doing business in China have a Chinese partner to which it must transfer all its technological and business secrets. And fourth was China’s promise to buy some $200 billion more of U.S. goods over the following two years.

It is, of course, difficult to measure compliance on some of these scores, but there are positive signs. The yuan has fluctuated as is the case with all foreign exchange, but shows no sign of outright manipulation. Beijing has relaxed its insistence that American business in China have a Chinese partner and instituted civil and criminal procedures for patent and copyright infringements.

On the additional purchases, the statistics speak loudly. According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, U.S. goods exports to China have risen at almost a 14.5 percent annual rate since 2019, far faster than the 0.6 percent yearly growth in all U.S. exports during this time and also faster than the 1.25 percent annual growth of U.S. exports to China during the three years prior to the deal. The recent acceleration in exports to China is still more impressive since changes in U.S. sourcing have otherwise reduced the export of American components to China for assembly.

With American purchases in China slowing and Chinese purchases of American goods accelerating, the balance of trade between the two countries has become much less lopsided. The Commerce Department puts the worst bilateral trade deficit in 2018, when China sold this country $419 billion more goods than the United States sold in China. As of the first three months of 2021, that difference was running at a $284 billion annual rate, sill a huge deficit but a correction (if that is the right word) of about a third.

Whether this trend continues depends on policies coming out of Beijing and Washington as well as the inevitable ebb and flow of economic cycles—in the United States and China and just about every country in the world that competes with either this country or China. But for the time being, a major source of tension is abating.

Friends Read Free