The unraveling of Chinese property giant Evergrande, the world’s most indebted developer, has prompted an unusual intervention by a U.S. investor.

Evergrande had invested billions of dollars in the coastal project in Jiangsu Province, which features 66 million square feet of residential space. Oaktree also took over a huge plot of undeveloped Hong Kong land from the flailing real estate firm.

The audacious moves by Oaktree, a $161 billion distressed debt specialist, grabbed headlines and signaled that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)—which most likely approved the Shanghai deal—is still open to certain types of foreign investment.

The CCP has strategically opened China’s financial markets to foreign inflows in recent years, allowing global investors to take advantage of the relatively high returns of yuan-denominated assets. Global index providers, such as MSCI and S&P Dow Jones, have played a crucial role by dramatically increasing the weight of Chinese securities in emerging market indexes, automatically driving huge amounts of capital into the Chinese economy from institutional investors, pension funds, and other sources.

The scale of U.S. portfolio investment in China should raise concerns, even if most of the money flows to apparently harmless destinations such as prime real estate projects or e-commerce stocks. The influx of American and other foreign investment bolsters China’s capital account, counteracting U.S. efforts to influence the Chinese economy through policies such as tariffs.

But there is far more to the story, because under China’s military-civil fusion strategy, ostensibly civilian companies are compelled to support the CCP’s defense and intelligence activities. This means that seemingly innocuous foreign investments in China’s economy can be steered toward purposes that threaten U.S. national security, such as the development of technology with potential military applications.

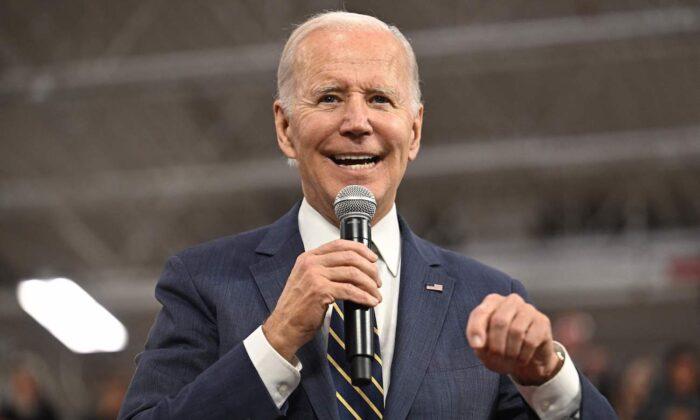

Former President Donald Trump moved to address this threat by banning U.S. individuals and investors from owning shares in any of 31 Chinese companies deemed to be assisting China’s People’s Liberation Army. President Joe Biden expanded the order to restrict companies that are believed to undermine the democratic values of the United States and its allies, such as by supplying technology that enables human rights abuses.

“Military-civil fusion transforms China’s military-industrial complex into a commercial ecosystem in which the aggregate efforts of firms, funds, and research institutes may pose risks not evident at the level of individual entities or transactions,” the U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission stated.

CNBC reported that U.S. firms Goldman Sachs and Bernstein Private Wealth Management are so bullish on the world’s second-largest stock market that they released thick reports recommending mainland Chinese stocks, or A-shares, in recent weeks. Other investors, such as Bank of America and J.P. Morgan Asset Management, are more neutral.

According to the report, “Were China to ‘catch up’ with other advanced economies, US–China portfolio investment would—all things being equal—triple in size, reaching more than $9 trillion compared to our estimate of about $3 trillion at the end of 2020.”

Friends Read Free