The U.S.–Africa Leaders Summit held in Washington at the beginning of August did little to advance a mutual agenda among the various parties. There at a great smokescreen event, African leaders smiled widely for the camera while holding the same old grudges toward their American partner. America, of course, remains oblivious to the demands of the African leaders. At least acknowledging their demands is a prerequisite for a long-term mutual and equal partnership.

At the beginning of August, the African continent basked in the limelight facilitated by news cycles relating to the summit. President Barack Obama hosted this event amid an ongoing crisis in Ukraine and another filibuster situation in the Middle East.

Being nothing more than one of the most expensive photo-shoots in Washington, the summit brought together the American leader with 50 African presidents, vice presidents, and prime ministers.

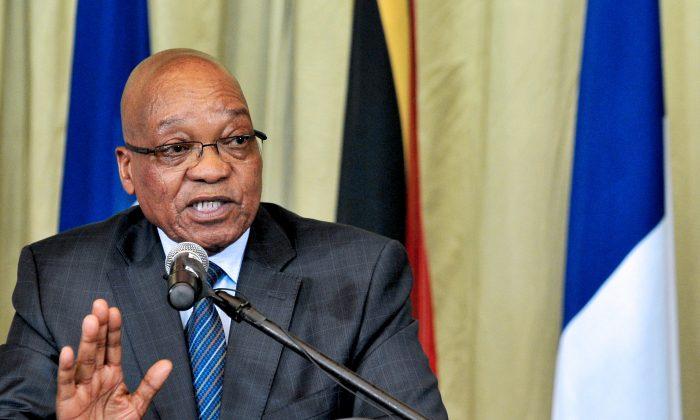

Among the notorious participants at the summit were Swaziland’s King Mswati III (forced to pay restitution to one of his wives’ family for improper relations with a 14-year-old girl); Idriss Deby of Chad (still in power after a full-fledged revolution in 2008 only because of French military intervention); Teodoro Obiang of Equatorial Guinea (whose son was accused by the U.S. Department of Justice in 2012 of siphoning $500+ million from U.S. aid for his own purposes); and Jacob Zuma of South Africa (who, after having relations with an HIV+ woman in 2005 reassured the world he is AIDS-free because he took a shower after the fact).

Recycled Topics

Not only were some of the African leaders present questionable, but the summit’s agenda as well left much to be desired. The panels focused on African trade and investment, security issues, and poverty alleviation. These topics have been recycled, with little to no effectiveness, since the World Bank’s inception 70 years ago. In brief, the summit once again reiterated an agenda, which the Western world has tried to implement—and failed—over and over again for much of the 20th and 21st centuries.

On the other hand, subjects considered most pressing by African leaders for the past decade were not discussed: knowledge transfer in the fields of agricultural production and military campaigns; U.S. foreign direct investment and lines of credit for infrastructure-related projects; and knowledge sharing of technological advancements.

For the American foreign policy intelligentsia, organizing the summit was mandatory in light of continuous mutual engagements between China and Africa. Since 2009 China, not the United States, has topped the list of Africa’s bilateral trade partners. Obama has been criticized over the last six years for not engaging enough in public debates and meaningful actions toward the old continent (save the 2009 Africa Tour, which was covered extensively, but produced few tangible results). So this was the American administration’s way of answering this criticism.

From an African perspective, being at the same table with the leader of the free world was a necessary and great PR boost before re-engaging their other partners.

At the summit, President Obama emphatically declared, “I see Africa as a fundamental part of our interconnected world—partners with America on behalf of the future we want for all of our children. That partnership must be grounded in mutual responsibility and mutual respect.”

Yet this beautifully crafted statement failed to address the core tension between U.S. and African leaders, pointed out succinctly by Paul Kagame, president of Rwanda, in an op-ed for The Washington Post in 2009:

“The United States has committed less to African markets than the emerging economies of Asia have; China guarantees nearly 30 times more in loans for investment in Africa than the United States[. …] Our markets need to be connected by better roads, by canals and ports, and through new technologies. Yet few U.S. companies are competing for large-scale and regional projects.”

Thus I return to my first point—that the summit was merely an expensive photo-op, a PR stunt for the world to see Americans indulging in the illusion that our government seriously engages with the African continent. However, the reality is obvious and straightforward: the United States is not prepared to meet African leaders halfway on anything other than topics benefiting the American agenda. Imagining that our African counterparts don’t see this is not only naive but also insulting.

China Squeezing In

China’s engagement with Africa over the last 10 years has produced an irreversible rupture in the Western world’s “business as usual” approach to the continent. Begun with structural adjustments in the 1980s, the West’s approach was simple: African leaders had to comply with a series of stringent regulations before funds would be released for any specific projects. Africa was the child at the table who could only speak when first spoken to, or risk getting nothing. When China began engaging African leaders after 2004, the game changed: if America would not meet certain requests from African leaders, China was willing and able to do so.

Certainly, China’s engagement in Africa is not altruistic in its nature—as many have observed previously it is driven by China’s unquenchable thirst for Africa’s resources (minerals, oil, land) as well as Africa’s un-matured markets (where small scale Chinese entrepreneurs can easily compete and drive business). But the Chinese state was willing to take on infrastructure projects (much needed all over the continent) as well as opulent requests from autocratic African leaders (palaces, stadiums, airports, etc.). This prompted Robert Mugabe (Zimbabwe’s president) to declare emphatically, as early as 2005, “We have turned east, where the sun rises, and given our back to the west, where the sun sets.”

Yet China’s influence in Africa is often overrated. I believe this is where tighter relations between the United States and African leaders can certainly pose a threat to the rising Chinese soft power effects in Africa in the long term, provided that the United States can make certain concessions. Unfortunately for now, America has yet to adapt to the new rules of the game. We’re stuck in the old definition of insanity: repeating the same action, expecting different results.

Codrin Arsene writes about African political and cultural affairs. He is a Chicago-based anthropologist who lived and worked in Tanzania and Uganda.