Is there a dish more beloved the world over than pizza? Whether you’re pulling up your chair to a checkerboard tablecloth in a small Cambodian village or popping off the train for a quick snack at a Trans-Siberian railway station, you'll find it everywhere. That savory combination of meat, cheese, and dough is ubiquitous—and, usually, pretty delicious.

Like many famous dishes, you can trace its provenance back to one place: Naples, the largest city in southern Italy. And on a recent trip there, dodging mopeds in the narrow laneways and walking along the sultry waterfront, I learned some of its secrets.

First and foremost, something that isn’t a mystery: Neapolitans love their pies. Walk a few blocks and you’ll find more pizza than you’ve ever seen in your life. While it’s probably not technically true, it feels like every corner in this city of about 3 million is occupied by a pizzeria. And the tables aren’t just filled with tourists—on any day of the week, you’ll find plenty of locals enjoying a slice, too.

Even the ancients consumed flatbreads, but this particular combination became popular in Naples in the 18th and 19th centuries. The city was (and, in some ways, remains) a rough-and-tumble port, home to thousands of working poor collectively called the lazzaroni. They needed food that was filling and cheap, and the humble pizza did the trick.

It may be apocryphal, but as the story goes, Italian King Umberto I and Queen Margherita visited the city in 1889. They were tired of all the fancy food they’d been served on their trip and wanted to try a slice of this popular Neapolitan dish. The queen particularly enjoyed a pie with mozzarella, cherry tomatoes, and basil; henceforth, it was known as the Pizza Margherita.

I came to town with a single plan. I wasn’t here to see Pompeii or to attend a soccer game. I was here to eat pizza, then walk around for as long as it took to get hungry enough to eat pizza again. I had very humble slices, including a tiny little finger of pizza given to me free by a microbrewery as a reward for ordering one of their pilsners. I avoided any place too touristy, including L'Antica Pizzeria da Michele, which serves only two kinds of pies: Margherita and marinara. People queue up for hours to eat at the same place where Julia Roberts, playing Elizabeth Gilbert, had a slice in the blockbuster film “Eat Pray Love.”

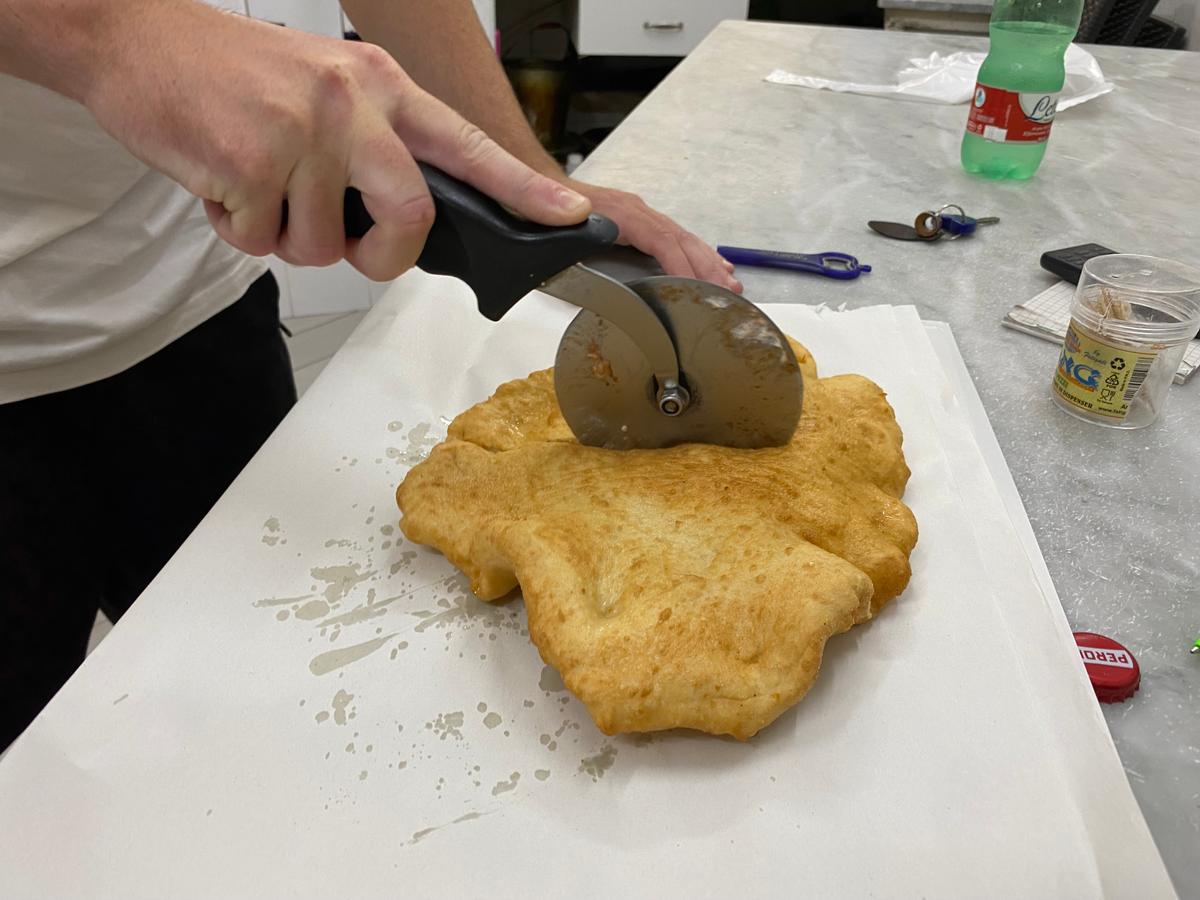

I also tried something new, at least to me: fried pizza (pizza fritta). Walking a few blocks from my hotel, I entered the Spanish Quarter, a frenzied corner of the city made up of a labyrinth of tiny, ancient lanes. Here, the parties, fueled by one-euro Aperol spritzes, often rollick into the wee hours.

Arriving in the early afternoon, I found Pizza Fritta da Gennaro to be a tiny—and busy—family-owned business staffed by an uncle (Antonio) and his nephew (Giovanni). Occupying a corner where two narrow streets intersect, the kitchen was separated from the lane by a rope across the door, and there were no public tables available. It was clear that most business here was takeout. When I mentioned that I’d love to sit and chat while I enjoyed my first fried slice, they graciously pulled back the rope and let me sit at a table right in the kitchen.

The Gennaros chatted with me as they prepared the food, frying the bread in a big vat of oil before filling it with red sauce and cheese.

“We’ve been here 18 years, but my grandfather started making fried pizza 50 years ago,” Giovanni Gennaro said.

Time, it seems, has turned out a delicious product—the sauce bright and flavorful, the cheese stringy and perfect, all rolled into chewy dough.

My single-minded explorations took me across the city. One gambol took me to Pizzeria Matteo, where all of their promotional materials, including the front of the menu, advertised the fact that Bill Clinton once dined here, decades ago, as president. Since the pizza was amazing, it wouldn’t surprise me if he still remembers it. I didn’t have a single mediocre slice the entire time I was in town.

But the best was in an inauspicious place, on my last night in town. I’d planned on going to Antica Pizzeria Port’Alba, reported to be the oldest in town. But after all the walking—not to mention the pounds of mozzarella already in my stomach—I opted for something close by. Looking online, I found a hole-in-the-wall pizza parlor, just around the corner.

It wasn’t stylish, with its garish sign and harsh inside lightning, but the reviews were over-the-top; glowing, as bright as the sign. The waiters didn’t speak English.

And the pizza was perfect. Sitting on a wobbly chair at a metal table on a busy street, I could see the tiled, wood-burning oven through the window. The fire burned, orange and hot, inside. A cook went about his business steadily, kneading the dough, spreading the sauce, and portioning out the cheese, methodical and meticulous, a magician performing a trick.

They brought me the pie, a Margherita with buffalo mozzarella. The first bite was glorious. The sauce tasted like springtime. The cheese, like little pillows of heaven, was so good that it made my eyes water. (I’m not crying, you’re crying.) It was a meal fit for royalty but served in a place where even the lazzaroni would feel comfortable. A perfect final pie, here in the birthplace of pizza.

If You Go

Fly: Very close to the heart of the city, you can hear and see the almost-constant air traffic landing at Naples International Airport (NAP) from many of its historic neighborhoods. While there are few direct connections to North America, both low-cost carriers and national flag-bearers link Naples with major cities across Europe, and beyond.

Friends Read Free