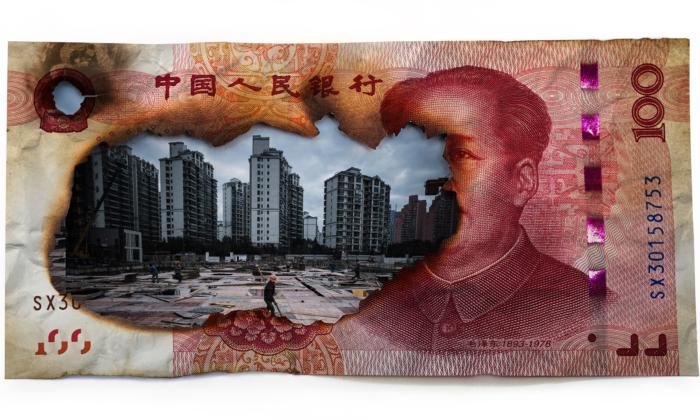

The real estate industry accounts for 25 percent of China’s GDP, and more than one-third of local government revenues are tied to either land sales or home sales.

But mounting problems—with no obvious solutions—are threatening to destabilize not just the real estate sector but China’s banks and industrial producers. It’s a “gray swan” problem that has long simmered but may finally tip over.

Despite recent attempts by Beijing to bolster the country’s real estate markets, combined sales at China’s top 100 property developers in July fell by 29 percent from June and by 40 percent year-over-year. This is after two consecutive monthly increases, according to data released by China Real Estate Information Corp. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has attempted to shore up housing demand since at least March, introducing measures such as reducing the required down payment and cutting mortgage rates.

There are question marks around whether the recent measures had enough time to make an impact or were too weak to offset negative market sentiments.

The average selling price of pre-owned housing across 100 Chinese cities also declined in July. It was the second straight monthly decline. Home price declines were most notable in smaller cities (third and fourth tier) while first and second-tier cities showed some resilience.

Mortgage boycotts continue to plague developers throughout the country, complicating Beijing’s efforts to rescue the real estate industry.

Many homebuyers boycotting paying mortgages complained that their monthly mortgage payments had not been held in escrow accounts as stipulated in the purchase agreements, but were siphoned out of those accounts by cash-strapped property developers.

Let’s examine both the cause and effect of this phenomenon, which could further destabilize an already tottering real estate sector.

The issue is rooted in China’s “presale” system, where buyers typically begin making payments to purchase an apartment before the apartment is built. Typically, a down payment is made and then the buyer begins making monthly mortgage payments during the construction process. This system helps developers raise cash quickly to buy new land and start new developments.

Until recently, developers had ample access to debt financing and were allowed to use the bulk of this presale revenue for whatever they wanted, only setting aside a small amount to finish the construction of the housing project.

But in the last 12 months, developers have become increasingly cash-strapped while Beijing has imposed more stringent restrictions on how the cash can be used. This created a “catch-22” where many developers ran out of cash before fully finishing the apartments, leaving masses of angry customers in their wake.

Recently, lax supervision and oversight within some localities had allowed some developers to tap into this presale cash supposedly held in escrow accounts to fund new land purchases. Recall that it is in the best interest of local governments to unlock this cash, as land sales to developers are a key revenue source for municipalities.

Those transfers were also made through kickbacks from contractors, where developers moved more cash out of customer escrows than necessary to construction companies, which in turn transferred the excess back to the developers. Customers only saw that cash was used for construction, a permissible expense from the escrow accounts.

This underscores the deep-seated problems plaguing China’s developers and their business model. Absent a massive bailout from the CCP regime, it’s impossible to envision how the real estate industry can pull itself out of this downward spiral.

Meanwhile, problems are compounding for developers. Developer Shimao Group Holdings Ltd. was sued by Singaporean bank United Overseas Bank Ltd. in Hong Kong for breach of contract concerning certain loans the bank had given the developer.

Chief Executive Officer Xia Haijun of China Evergrande was recently forced to resign—along with the firm’s CFO—in the middle of a lengthy restructuring process. Evergrande has been the poster child of China’s real estate sector woes.

The other side of the coin is downstream customers. Buyers fed up with the status quo system and boycotting mortgages are creating issues for both banks and developers. The nationwide mortgage boycott began at an Evergrande housing project in Jiangxi Province.

Yet today, protests have spread beyond mere customers. Dozens of contractors such as construction companies and landscaping firms have also halted their debt payments, citing an inability to pay their debts due to money owed to them from developers.

The unanswered question is how much this turmoil in the real estate industry will impact China’s broader economy, specifically the $50 trillion banking system.

Banks are caught in the middle of this crisis. The real estate industry is Chinese banks’ biggest source of business—providing a stable foundation in prior periods of market disruptions—yet it could prove to be their undoing.

If banks don’t step in and provide loans to developers to help finish projects and induce buyers to pay, they will stand to lose more money. But stepping in is also undesirable—it is increasing their exposure to a failed industry and potentially more risks later.

S&P Global estimated that 2.4 trillion yuan (about $355 billion) of mortgages could be at risk of being unpaid. That amounts to around 6.5 percent of all outstanding mortgages.

Bloomberg reported that China’s national auditor is investigating the country’s $3 trillion shadow banking sector. Among its top concerns are these financial companies’ outstanding loans to real estate developers and how they plan to recoup or dispose of such loans. China’s top 20 trust companies and shadow banks are taking part in this investigation to assess the industry’s impact on China’s financial stability.

China’s steel industry, an important employment pillar in the country’s northeast, has also struggled in the wake of real estate turmoil. Once seen as a major source of China’s economic expansion into a global supplier and consumer, Bloomberg recently reported that almost a third of China’s steel mills could go bankrupt, citing comments from the founder of Hebei Jingye Steel Group.

Weaknesses in the steel industry also have caused upstream issues such as lower iron ore prices hitting global miners, producers, and commodity traders.

Friends Read Free