Revelations that World Bank leaders pressured staff to rig an influential report in China’s favor have once again shed light on the Beijing regime’s influence within the United Nations system.

The fallout from the probe has been swift. The World Bank announced its abandonment of the Doing Business report entirely. Georgieva, now head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), has faced calls for her resignation, including by The Economist magazine. The embattled chief, however, has vehemently denied the investigation’s findings.

Analysts now say that the scandal has further underscored the Chinese regime’s malign influence in important multilateral institutions.

China’s communist regime sees the existing international order as a threat to its interests, Seth Cropsey, a senior fellow at the Washington-based think tank Hudson Institute, told The Epoch Times. “So they want to break it up whenever possible.”

“Influence and membership and participation in international organizations give them the foot in the door that they need to accomplish that goal.”

History of Collaboration

The World Bank played an important role in shaping the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) economic reforms in the 1980s and 1990s, when the regime was attempting to extricate the country away from backwater status, according to China expert Michael Pillsbury.While the lender released “a few vague reports” about China’s need to develop free markets, in private, the World Bank by the mid-1980s endorsed the regime’s socialist approach and “made no genuine effort to advocate for a true market economy,” Pillsbury wrote.

China’s Influence

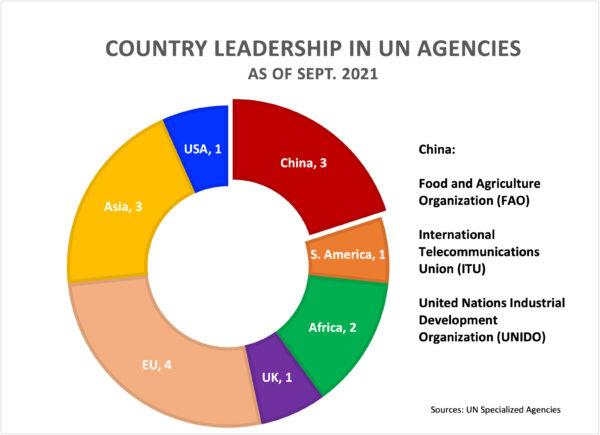

The IMF and World Bank are among 15 U.N. specialized agencies, of which Chinese representatives head three. No other country leads more than one body. Meanwhile, the International Civil Aviation Organization just saw its Chinese chief depart in August after a seven-year term.“Since I wrote The Hundred-Year Marathon six years ago, the Chinese have not suffered any significant sanctions that would cause them to change their successful trajectory to surpass the U.S. in global primacy,” Pillsbury wrote.

The CCP’s only recent setback in the U.N. system, according to Pillsbury, occurred when the Chinese candidate was outvoted for the top post at the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO).

In the lead up to WIPO’s March 2020 election, the Trump administration mounted an effort to ensure that Wang Binyang, a representative of the Chinese regime—which is notorious for its lack of intellectual property protections—wasn’t successful in his bid to lead the body charged with safeguarding those rights worldwide.

Wang was ultimately defeated by Singaporean Daren Tang, who was backed by the United States and many other Western nations, by a vote of 28 to 55.

Pushing Belt and Road Through UN

The Chinese regime also has used U.N. bodies to legitimize and promote its massive global infrastructure investment project, known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The trillion-dollar plan has been criticized by U.S. officials for facilitating the expansion of Beijing’s economic and military clout, while saddling developing countries with unsustainable debt burdens.Through these efforts, the Chinese regime has been able to package its BRI projects under the U.N.’s sustainable development goals, the report said, thus allowing U.N. resources to be directed toward Chinese-backed investments.

The WHO, led by Hong Kong’s Margaret Chan from 2007 to 2017, also promoted the BRI in the health care sector.

The agreement paves the way “for client states around the world to use Chinese technology, products, and software in hospitals and other organizations relating to global health,” Easton said.

The World Bank and IMF didn’t respond to questions from The Epoch Times relating to the CCP’s influence in U.N. systems. WHO officials also didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Friends Read Free