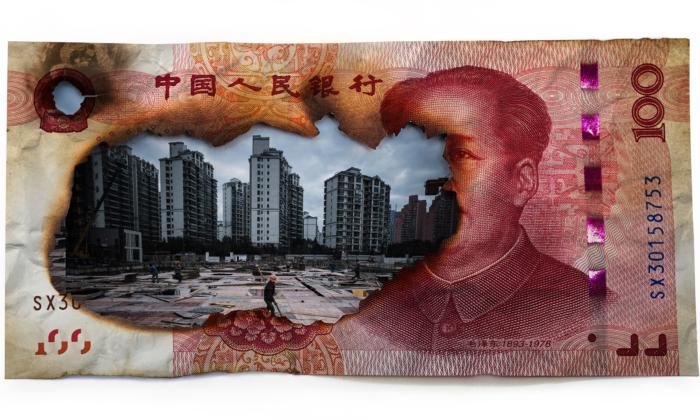

China Evergrande, mainland China’s largest property developer by sales volume, has been under pressure lately from investors dumping its stocks and bonds on fears that the company—a bellwether for China’s real estate sector—is in dire financial straits.

The developer is highly indebted, and its ongoing troubles could signal upcoming pain for other highly levered Chinese companies as the world’s No. 2 economy suffers from a prolonged economic growth slowdown.

Evergrande’s woes—its common stock fell 9.5 percent and the price of its $1.2 billion offshore bond due June 28, 2021, dropped 4.1 percent to $87.51—on Sept. 25 were the result of a document leaked on Chinese social media a day earlier allegedly sent by Evergrande Group to the Guangdong provincial government. It warned that the developer is in a cash crunch and could be a systemic risk to China’s financial system if the government does not back a previously proposed company restructuring. It owes around 130 billion yuan ($19 billion) to various strategic investors it must repay by early 2021.

Shares of Evergrande subsidiaries Evergrande New Energy Vehicle Group Ltd. and HengTen Networks Group Ltd. also dropped by more than double digits. And two onshore bonds issued by subsidiary Evergrande Real Estate Group were suspended from trading in Shanghai after they declined almost 30 percent on Sept. 25.

Massive Debt Accumulated via Expansion

Foreign investors are closely watching how Evergrande’s financial situation evolves. Its offshore dollar-denominated bonds—paying annual interest up to 10 percent—are widely held by yield-starved institutional investors in the United States.The investment thesis on Evergrande was dependent on China’s recent economic growth and population migration patterns. More than 10 million Chinese move from rural to urban areas every year, and for a young person homeownership is often a “requirement” to live a decent life.

“It’s hard for Westerners to understand that a 26-year-old [Chinese] man has to own a place if he wants to get a wife,” Teresa Kong, lead manager of the Matthews Asia Credit Opportunities fund, told Barron’s earlier this year. “Household thrift leaves a large supply of buyers with the 30% to 40% down payment typically required. Most apartments are sold a year before they are built, reducing risk for developers.”

Evergrande may be “too big to fail” as one of China’s biggest developers—the importance of the country’s real estate sector to its survival cannot be overstated—but its massive debt load and recent moves suggest that allegations in the leaked letter may be true.

The company has been on a spending spree for years, buying up disparate assets such as soccer clubs, land, and farms. Its far-reaching footprint raises questions about its business model and focus. For example, Evergrande recently created China Evergrande New Vehicle Group by renaming an existing healthcare company subsidiary to jump into the electric vehicle boom.

Earlier this month, Evergrande kicked off a sales promotion with a 30 percent discount on all real estate nationwide, to increase sales and raise cash to meet its target of cutting its debt load.

Evergrande was one of a dozen property developers summoned to a meeting by Beijing authorities on Aug. 20 to brief them on a new policy to limit real estate companies from taking on additional debt.

Regulators announced a “three red lines” policy setting limits on bank borrowings by developers: a 70 percent ceiling on debt-to-asset ratio (excluding presales), a 100 percent limit on net debt-to-equity ratio, and cash holdings cannot be lower than short-term debt.

Companies breaching all three red lines would be barred from issuing more debt. And as of June 30, Evergrande has breached all three, according to data gathered by Bloomberg.

Indebted Chinese Companies

In general, China’s corporate debt has expanded exponentially in recent years. As of the end of 2019, it was 120 percent of GDP estimated by Macquarie Group, which is more than twice the level of the same U.S. metric. As a result of the CCP virus, debt growth is likely to increase.Corporate defaults had already surged to a record high in 2019, pre-pandemic. Most of that was yuan-denominated onshore bonds. Defaults on dollar-denominated bonds, which until last year were relatively safe with implicit state guarantees, hit $4 billion as of June, a 150 percent increase from last year according to data from Bloomberg.

What about other property developers? Shares of Sunac Holdings fell 5.2 percent on Sept. 25, while Country Garden Holdings fell 3.9 percent. Their bonds also sold off. Sunac, like Evergrande, has breached the “three red lines.” Country Garden is less levered relative to others but still has high ongoing debt service costs.

Macrolink Holding in March became the first Chinese property developer to default on its bonds as a result of the CCP virus.

Expanding debt load needs higher revenues to support and in a post-CCP virus environment, China’s real estate sales have not kept up. Contracted sales during the first half of 2020 are down from 2019 due to the pandemic. While housing prices have held steady across tier 1 and tier 2 cities compared to 2019, that trend is unlikely to last.

With new leverage limit placed on property developers, real estate companies will look to increase discounting in order to accelerate sales to raise the needed cash. Increasing sales at the expense of margins is a dangerous game, but property developers have few alternatives.

Built but unsold homes increased to 480 million square meters (5.16 billion square feet) across 100 mainland cities at the end of July, according to a Sept. 2 South China Morning Post report. That amounted to the highest level of housing inventory since November 2019.

If these trends persist into the end of the year, the Chinese real estate market is in for a reckoning.

Friends Read Free