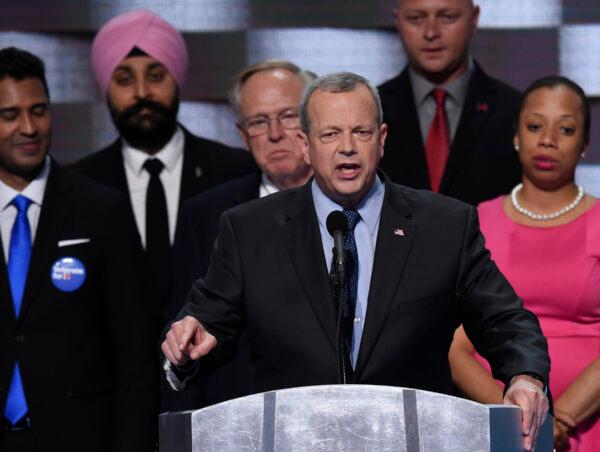

A newly released FBI affidavit implicates the president of the Brookings Institution, retired four-star Marine Gen. John Allen, in an alleged backchannel effort in 2017 to lobby then-Trump administration national security adviser H.R. McMaster, as well as other U.S. government officials, on behalf of the government of Qatar.

Allen is alleged to have made false statements and concealed documents from the FBI in connection with his lobbying efforts.

Late last month, Olson’s lawyers complained to the judge assigned in the case that Allen, who they claimed was part of the same lobbying operation, hadn’t been charged with any crime. Olson had been cooperating with the FBI under a limited use immunity agreement since October 2020. The agreement precludes the government from directly using Olson’s statements to investigators against him.

The affidavit alleges that Olson, Allen, Zuberi, and Ahmed Al-Rumaihi, a high-ranking Qatari government official for whom Zuberi worked, set out to “convince the United States to intervene, defuse the possibility of sanctions, and negotiate a resolution favorable to Qatar.”

At first, the lobbying efforts appeared to be above board. On June 6, Zuberi and Olson met with Rumaihi and an attorney at the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C., to discuss their campaign. According to Martin Van Valkenburg, a Zuberi associate who is now cooperating with the FBI, the plan was for the attorney to register under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) and coordinate the lobbying efforts with Rumaihi.

However, Olson and Zuberi had at the same time also allegedly initiated a behind-the-scenes backchannel effort involving Allen. According to the affidavit, on the evening of June 6, Olson introduced Allen to Zuberi via email. They spoke on the phone the next morning and later met for lunch, again at the Willard Hotel. According to Van Valkenburg, Allen suggested writing op-eds in support of Qatar. He offered to find authors and said that he would consider writing op-eds personally.

The next day, June 7, Allen allegedly told Olson that he needed to “have a chat about numbers” in connection with his assistance. Allen suggested traveling to Doha, Qatar, for “a speaking engagement” that could be used as a pretext for getting paid for his help in the lobbying effort.

“What we can do is call and treat my visit to Doha over the weekend as ‘a speaking engagement,’ which I’ve done before, for which I’d be compensated at my standard rate. Then we can work out the fuller arrangement of a longer-term relationship over the weekend,” Allen wrote in an email.

Zuberi agreed to pay Allen a “speaking engagement” fee of $20,000. Notably, Allen’s email states that he had used the same “speaking engagement” pretext before. It isn’t clear from the affidavit whether the FBI is looking into any previous instances involving Allen being paid for lobbying activities under potentially false pretenses.

On June 8, Olson, Allen, Zuberi, and Rumaihi met in Washington. According to Van Valkenburg, it was at this meeting that Rumaihi requested an official statement from the U.S. government asking for de-escalation.

The next morning, June 9, Allen emailed McMaster and requested that the White House or State Department issue a statement “calling on all sides to seek a peaceful resolution to this crisis [and to act with restraint].”

Allen told McMaster that he was “close to the Qataris” and that he was merely relaying their request. Allen didn’t mention the nature of his involvement, the other participants, nor that he was being paid for his efforts. According to the affidavit, McMaster has since given a statement to the FBI confirming that Allen concealed this information.

On June 10, Olson, Allen, and Zuberi traveled to Qatar where they met the emir, the emir’s brother, the Foreign Minister, the Defense Minister, and other senior Qatari officials. According to notes which Olson handed to the FBI as part of his immunity agreement, the discussion centered on “how to convince the Trump Administration to help Qatar with respect to the diplomatic crisis.”

According to the affidavit, Allen and Olson also conveyed to the emir that while they were private citizens, they had “connections with Trump Administration officials that placed them in a position to help Qatar.” They specifically named McMaster, Tillerson, former Defense Secretary James Mathis, and former Secretary for Homeland Security John Kelly.

Olson’s notes of the meeting also state that Allen and Olson told the emir that they “could mold the opinions of U.S. officials, through McMaster.” They further allegedly suggested that “the Qatari government use the United States’ Al-Udeid Air Force base in Qatar as leverage to exert influence over the U.S. government.”

Afterward, Allen and Olson met with the Qatari Minister of Defense, with Allen allegedly advising the minister to use “the full spectrum of info ops. - black and white” to “control the narrative.” Black ops are covert operations by government operatives carried out in a way that conceals their involvement.

On June 11, McMaster replied to Allen by email: “We received the message and have sent private communications that calls for restraint and a rapid end to the crisis/relaxation of the blockade. I look forward to hearing your advice.”

After his return to Washington, Allen spoke to McMaster by phone on June 15; the affidavit doesn’t state what was discussed on the call. Later that same day, Olson, Allen, and Zuberi met with the emir’s brother at the Hay Adams Hotel in Washington. According to Olson, Allen told the emir’s brother that he had briefed McMaster and Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner. The next morning Allen emailed McMaster requesting that McMaster meet with the emir’s brother and the Foreign Minister of Qatar.

In a same-day email, Zuberi complained that the emir’s brother had apparently made a similar request through official diplomatic channels.

“He is stupid to have the Qatari Embassy in Washington make the request when General Allen said he will handle it.”

At this point, Allen apparently became concerned about using email to communicate and suggested that the group switch to the WhatsApp messaging service. Allen also noted that he wouldn’t be able to personally attend any White House meetings but that McMaster would brief him afterward.

Having not heard from McMaster, Allen followed up on June 23. McMaster replied on June 25, telling Allen that Tillerson was taking the lead with respect to the Qatar crisis. Allen conveyed the news to Olson and Zuberi: “I wish this was better news.”

On June 27, Tillerson met with the Qatari foreign minister, apparently without McMaster.

Allen’s role wasn’t limited to lobbying the Trump administration. According to the affidavit, on June 7 and 13, Zuberi personally conveyed Qatar’s standpoint to Rep. Ed Royce (R-Calif.), the former chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee. After the meetings, Zuberi reported back to Allen and Olson. Then, on June 16, Allen met with an unknown member of Congress at the Cosmos Club in Washington, and on June 28, Allen and his group met a number of members of Congress “to discuss the situation in Qatar, the US’s response,” according to the affidavit.

Members of Congress who were scheduled to attend included Reps. Royce, Eliot Engel (D-N.Y.), Joe Wilson (R-S.C.), Ted Lieu (D-Calif.), David Cicilline (D-R.I.), Maxine Waters (D-Calif.), Tony Cardenas (D-Calif.), Ruben Kihuen (D-Nev.), Stephanie Murphy (D-Fla.), and Salud Carbajal (D-Calif.). Royce, Wilson, and Lieu have since confirmed that they attended the meeting.

The FBI affidavit raises many questions pertaining to issues such as McMaster’s role or why Tillerson suddenly changed course. However, the issue that stands out most prominently is the one that Olson’s lawyers raised: Why has Allen not been charged with FARA violations despite the documentary evidence produced in the FBI’s affidavit?

The Brookings Institution didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Friends Read Free