In any discussion of China and its global relationships, reference to “100 years” or “150 years of humiliation” of China by the West is bound to be made. Never mentioned are the 50 to 100 years of “salvation” from the West without which there would be no China today.

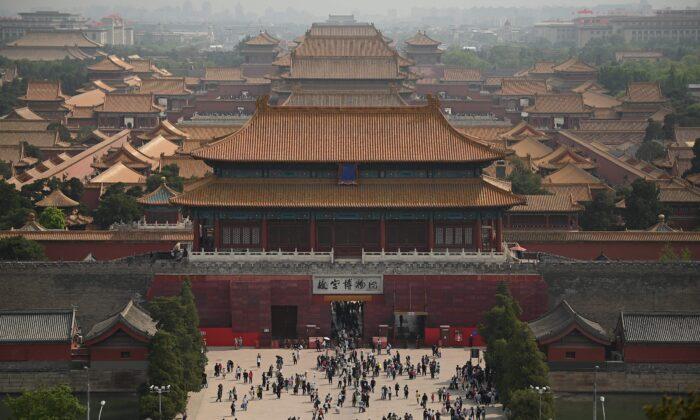

China, like Egypt and Iran, is a country with a long history of 3,000 to 5,000 years, depending on how one counts. In that time, it has been engaged in many wars and has often been conquered. Indeed, two of its greatest dynasties were foreign. The Yuan Dynasty was established by Mongol leader Kublai Khan in 1279. It lasted nearly 1,000 years and expanded China to its largest extent ever, indeed far larger than today’s China. Likewise, the Qing Dynasty was Manchu rather than Chinese. It marked the second largest historical extent of China and still serves as the geographical model of present-day China. Indeed, it is ironic that Xi Jinping’s great “Chinese Dream” is that of the Manchus rather than the Chinese.

It is interesting that China’s leaders today do not speak of humiliation by the Mongols and the Manchus whose leaders did not even speak Chinese, but rather embrace them as the model for the realization of their “Chinese Dream.”

The great humiliation to which Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders constantly refer was the Chinese defeat at the hands of Britain, France, Portugal, the United States, and Japan in the so-called Opium Wars of the latter 19th century. These countries wished to trade for China’s silks, tea, and porcelain. China, however, refused to accept much in payment except silver. As they ran short of silver, the Western powers scoured the world for something the Chinese might buy and discovered opium. China’s emperors tried to ban importation of opium, but the Western powers, especially Britain, sent their navies to enforce the trade. China’s technology and military capacities had fallen far behind those of the Western powers during the preceding 100 years and the emperor’s forces lost two wars to them and then, in 1895, a war with the Japanese who seized the island of Formosa and made it a colony. Hong Kong island was transferred to British control, the trade in opium was continued, and extra-territoriality (foreign citizens were not subject to Chinese law while staying in China) for Western citizens was established.

While certainly humiliating, this was not the total conquest of the Mongols or the Manchus. It was not loss of the total power to rule China’s own citizens. In contrast to the battles with the Mongols and Manchus, very few Chinese citizens were killed in the Opium Wars and the war over Formosa with the Japanese. Nor was China occupied and its citizens sent to fight the wars of its foreign conquerors.

In the wake of the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911, China went through difficult times as a variety of war lords carved the country up, the Communist and Nationalist Parties strove to achieve dominance, and the Japanese began to invade first Manchuria and then China proper. During these trying times, Western teachers and missionaries established schools and hospitals in China with funds sent from Western churches and philanthropists. Many of China’s top medical centers, schools, and universities today had their origins in these efforts by the West to help China.

Japan invaded and occupied Manchuria in 1931–32 and China proper in 1937. As Japan expanded the area of China under its control in 1940–41, the United States halted its export of oil to Japan. The reason for this was to force the Japanese to halt their further conquest of China. The U.S. embargo triggered Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor and the ensuing war in the Pacific. In the course of the war, the United States poured weapons, money, and U.S. soldiers from India, over the hump (of the Himalaya mountains), into China to halt the Japanese onslaught. While the United States was doing this, the Chinese Communist Party under Mao Zedong was avoiding combat and hiding in far northwest Yan'an.

After the conclusion of World War II, Chiang Kai-shek’s army was upon the point of complete conquest of Mao’s communist forces in 1948 when U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall intervened and forced Chiang to accept a coalition government with the CCP. This eventually led to the complete dominance of mainland China by the CCP in 1949. Mao never thanked Marshall, but he should have.

Then, in 1972, as the Soviet Union was increasingly hostile to China, who should call on Mao but U.S. President Richard Nixon with his so called “opening to China.” This is often presented in the press as a masterly diplomatic move by Nixon to wean China away from its old alliance with the Soviet Union. But, in truth, it was a masterly move by Mao and Zhou Enlai to obtain Washington’s protection of China from the Soviet Union while also obtaining formal U.S. recognition of the Chinese communist regime and the U.N. Security Council Seat that heretofore had been held by the Chinese Nationalist Party in Taiwan.

Then, in the fall of 1982, I was a leader of the first U.S. trade mission to China. For the next 40 years, the United States opened its markets and transferred its technology and production to China in the hope that China would evolve into a truly market economy and into a more liberal polity. With this American help as well as by dint of its own hard work and good policy, China has become by some measures the world’s largest economy and, according to Xi Jinping, an economy that has wiped out poverty.

In view of all this, why is it that one hears constantly of the humiliation of China by the West in the 19th and early 20th centuries with never a word about the salvation the West has provided to China in the latter 20th and early 21st centuries?