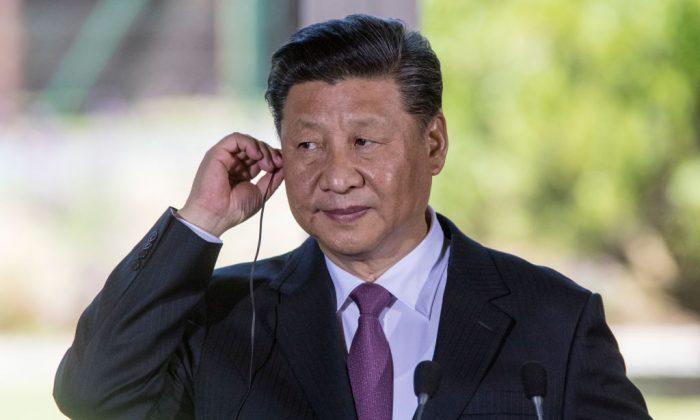

WASHINGTON—After meeting with President Donald Trump in Argentina on Dec. 1, Chinese leader Xi Jinping said he intends to list fentanyl as a controlled substance, “meaning that people selling fentanyl to the United States will be subject to China’s maximum penalty under the law,” according to a statement from the White House.

Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid, is 50 times more potent than heroin and 100 times more potent than morphine, according to the

CDC. It is used legally in the United States to treat severe pain and for people who are immune to weaker painkillers.

Its potency has made it increasingly popular in street drugs, such as heroin, and even street-sold pharmaceuticals like Percocet that can catch users by surprise, often with deadly consequences.

In 2016, the latest year for which the CDC has final data,

19,413 people died of synthetic drug-related overdoses. This is up from

9,580 in 2015—an increase of more than 100 percent. The

CDC says the spike was likely driven by illicitly manufactured fentanyl.

Experts agree that the majority of the clandestine fentanyl that is coming into the United States is made in China, which is possibly why some of its street names include

“China Girl” and “China White.”“What [Xi] will be doing to fentanyl could be a game changer for the United States,” Trump told reporters after the meeting on Dec. 1.

China has already taken action to schedule as controlled substances some fentanyl-related drugs such as

carfentanil, and some of the chemicals used to manufacture fentanyl, such as NPP and 4-ANPP. But so far, it has resisted classifying all fentanyl-related drugs as such, which Chinese drug manufacturers have used to their advantage.

By tweaking the chemical structure of the drug, they have made knockoffs known in the law enforcement world as “fentanyl analogues,” that have a similar effect, but technically aren’t illegal.

As these analogues pop up, and usually at the behest of the United States or other recipient countries, China undertakes a lengthy process to ascertain whether they should be classified as scheduled drugs. By the time they are, Chinese drug makers have created more analogues that Beijing then has to review and label.

“China ... has been increasingly cooperative with the United States in this area. Their actions are steps in the right direction, but more can be done,”

Paul Knierim, deputy chief of operations at the U.S. Office of Global Enforcement, told a House Foreign Affairs subcommittee in September. When pressed further about whether cooperation was happening at the highest levels of government, Knierim only stressed that the cooperation from his counterparts in China was encouraging.

In August, Trump complained in a

tweet about “poisonous synthetic heroin fentanyl” being shipped to the United States through the U.S. Postal Service.

In response, Yu Haibin, a senior official with China’s National Narcotics Control Commission,

said his comments were “irresponsible” and that the United States had “no proof” that the majority of fentanyl was coming from China.

That same month, the United States released a 43-count indictment of two Chinese nationals for operating a conspiracy that manufactured and shipped fentanyl analogues and 250 other drugs to at least 25 countries and 37 states.

Yu told the state-run

Global Times that the pair were not being indicted “according to the Chinese law and evidence.” The Justice Department said in its

announcement of the charges they had evaded Chinese law by manufacturing analogues.

A

report by the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, which was created by Congress to report on the national security implications of U.S.-China trade, said part of the problem is that the regulatory environment around drugs in China is very weak.

“China’s inefficient chemical and pharmaceutical regulatory environment is due in part to misaligned incentive structures for local governments, which are encouraged to prioritize economic growth and development objectives above all else,” wrote Sean O’Connor, a policy analyst with the commission and the author of the report.

It also notes a lack of political will to crack down on an epidemic that so far hasn’t created a problem in China.

In 2016, U.S. negotiators thought they had secured an agreement from Chinese regulators that they would prevent substances illegal by U.S. law from being exported to the United States.

“A Chinese readout from the same discussion, however, did not include making the commitment, and Beijing never implemented the policy,” the report says.

Jeffrey Higgins, a former supervisory special agent at the DEA, told the commission that he felt China was “merely seeking to create the appearance of cooperating with U.S. officials, while not enacting any reforms to its chemical and pharmaceutical industries that may slow the country’s economic growth.”

Friends Read Free